Pakistan’s fractured politics is in overdrive as the country heads into general elections next week after nearly two years of tumult and strife. At stake is not just who forms the next government but what shape of democratic governance emerges in the weeks and months ahead.

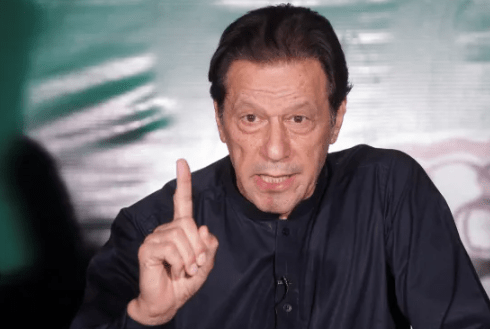

Former Prime Minister Imran Khan, hailed as one of the most popular politicians in the country, has already been knocked out of the contest. This week a local court handed down two jail sentences that also mean that he is barred from holding any public office for a decade. He can still appeal to the higher courts but as far as the February 8 elections are concerned, his name is already off the ballot.

There are, however, bigger issues at play in Pakistani politics today than the holding of an election. In fact, this electoral outcome may not fully reflect the multiple fault lines that have developed within the political and social fabric of the country.

These fault lines had started to emerge almost a decade ago when Khan and his party Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (Justice Party) had found traction among the voters and formed a government in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2013. After years of twists and turns in which Khan first found favour with the military establishment and then fell afoul of it, the real rupture happened on May 9, 2023. The events that transpired on this date – hundreds of Khan’s followers attacking, torching and ransacking military buildings across the country – have reshaped the politics of Pakistan. The tremors are reverberating to this day.

Since then, Khan and his supporters have faced the brunt of the law as well as a volley of desertions. The empire has struck back hard. The political colossus that was once the PTI today lies in shambles. Its supporters are crying foul and bemoaning the lack of the proverbial level playing field.

Few are however willing to admit that the blunders their leadership committed before and after the May 9 events have contributed in large part to their political ruination. Their black-and-white narrative of victimhood conveniently glosses over the varied shades of grey that paved the road to the party’s political Waterloo.

At the heart of Khan’s political misjudgements lay a misreading of the military establishment and its foundational role within the state. Civil-military relations in Pakistan may be a worn-out subject for public discussions and published dissertations but its practical manifestations, in many ways, continue to define how power is shared and exercised in the country.

Khan leveraged the power of the establishment to ride into power. He then used the same power to browbeat his opponents in a futile attempt to cripple their politics. But instead of further cementing this relationship, Khan committed the mistake of turning on his benefactor. The first schism opened over the key appointment of the head of the country’s premier intelligence agency. It never got repaired.

In fact, it widened after Khan was ousted from government in a vote of no-confidence and decided to take on the military publicly. It was, as it turns out, an ill-advised move that betrayed a shallow understanding of the established power dynamics. In other words, Khan dangerously overestimated his power as a popular leader and attempted to convert this popularity into a quasi-rebellion against the established state structure.

The initial response of his support base to his harangue against military officials was rapturous. In every speech in front of adoring crowds, he would cross a red line and name generals as being responsible for the so-called conspiracy against him. Emboldened by a lack of pushback by the military, he kept upping the ante. His advisors egged him on by arguing he was the only politician with enough public heft to take on the military and win. But at some point, during the course of this dangerous brinkmanship, Khan lost his political moorings.

There is a thin line between attacking the military leadership and the institution itself. There is an even thinner line between drumming up a conspiracy theory about the US government plotting with the military to overthrow him and accusing the military of actual treason. Not only were Khan’s accusations inflammatory — they were also, as it turned out later, not backed by any evidence.

The May 9, 2023 events were therefore waiting to happen. When his followers attacked military headquarters in Rawalpindi and set aflame a three-star general’s home in Lahore, they were acting upon what was deemed by the party leadership as a final push to topple the military high command and decisively convert the country’s power matrix in Khan’s favour. For all practical purposes, it was a coup attempt.

Parallels drawn with Donald Trump supporters storming the Capitol building in Washington, DC are not far-fetched. The law took its course – often erring on the side of harshness – and Khan’s hubris brought his entire edifice down. For now.

In consequence, has democratic space shrunk in Pakistan? In many ways, yes. Has the establishment’s footprint enlarged? Yes, it has. Have Khan’s political rivals, whom he refused to acknowledge as legitimate stakeholders, taken advantage of his downfall despite the shrinkage of political space? Certainly so.

But is Khan really the victim his supporters are painting him as? Not really. Have he and his supporters acknowledged the grave blunder they committed on May 9? No, they have not. Have they acknowledged their misjudgements and missteps? They certainly have not.

Pakistan may not be enjoying its ideal democratic moment, but if the elections can herald a new chapter, howsoever short-lived, that moves politics beyond the hate-filled, us-against-them, vitriolic brand epitomised by Imran Khan, we may find the breather that we so desperately need to start a process of national healing.