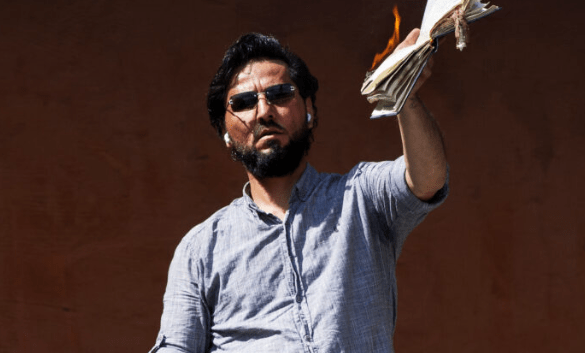

Sweden has a long history of being seen as a “moral superpower” dedicated to international assistance, progressive causes, and the welfare of developing countries, with a strong reputation for toleration and support for human rights. That Sweden is now being called a center of Islamophobia and intolerance is all the more shocking in light of this. The repeated burnings of the Quran, the most recent of which occurred over the weekend, have elicited a furious reaction from Muslims throughout. It’s hardly surprising that the Organization of Islamic Cooperation would raise objections, but the European Union and the Pope have also issued statements along these lines. Not everything that is legal is also ethical, as Josep Borrell put it.

As a result of Sweden’s entry into NATO, which essentially made Sweden’s bid subject to the whims of Turkey’s President Erdogan, the fires had already become a global blaze. A question of the place of religion and religious minorities in Swedish politics lurks just below the surface of the more pressing issue of national security. Sweden’s institutional framework is not just antagonistic to religion but also to communitarian claims in general, which conflicts with the Government’s verbal acceptance of human rights, including tolerance for religion.

The social compact in Sweden is built on a radical partnership between the state and the individual, as Henrik Berggren and I argue in our new book. Sweden is one of the most secular nations in the world. The primary goal is to free people from societal organizations like families, churches, charities, and government that restrict personal freedom in the sake of group membership. Furthermore, this ethical reasoning produces a civic universalism that is inimical to communitarian claims, including and particularly religious ones.

In surveys like the World Values Survey, Sweden stands out as a leader in this area. Sweden stands apart in stark contrast to the Islamic world and other Western nations like the United States and Germany, where social contracts provide religious and ethnic groups a far larger role. To practice one’s faith privately is fundamental to the Swedish concept of religious freedom. As a result, in Sweden, the concept of religious freedom includes the opposite of religious belief as much as it does the right to religious belief.

Only in congregations understood of as private, voluntary groupings can the practice of faith in God or gods occur outside of the house and the individual mind. A church’s public actions should be consistent with the norms of our secular society. This “civil religion,” concerned with such issues as citizenship, gender equality, and children’s rights, invariably prevails over what are viewed as conservative assertions with their origins in antiquated, premodern conceptions of religious faith and moral standards articulated in different religious scriptures. Therefore, the constitution and regulations of the contemporary, secular state should take precedence over the “holy” writings of religion.