Reuters – Battagram, Pakistan, August 26. After spending 16 hours stranded on a cable car over a river in northern Pakistan this week, student Ibrar Ahmed is grateful to be alive, but he worries about how he will manage to make the long journey to school every day.

After the dramatic events of Tuesday, he added, “God willing, I am going to continue with my studies, but the way to our school is so long.”

“Sometimes… I get late for school because it opens at 8:30 a.m. and the road is so perilous,” said Ahmed, a freshman at Batungi Pashto Government School. We have to use the elevator, but nobody wants to since it scares them.

After a line snapped and left them hanging 183 meters (600 feet) over the hilly Battagram area north of Islamabad, the military and residents of Pakistan rushed to their rescue.

The terrifying experience draws attention to a dilemma in Pakistani children’ access to education; few high schools, bad roads, poverty, and harsh weather all make it difficult for pupils to travel to school.

Because of this, Pakistan has the second-lowest rate of school enrollment in the world. Government statistics and World Bank data show that about 23 million Pakistani children between the ages of four and sixteen are not in school, with the situation being much more dire for females.

Analysts and economists agree that increasing Pakistan’s literacy rate is crucial to the country’s long-term economic health and for reducing the security threats that afflict the South Asian nation, which are worsened by the allure of terrorist organizations in Pakistan’s poor rural regions.

The Director of education at UNICEF Pakistan, Ellen Van Kalmthout, cited “long distances and travel times, few transportation options, and costs” as obstacles to females’ access to school in Pakistan.

Ahmed hopes that his hamlet will soon get “a proper road” and a high school.

SEVERAL CRASHES

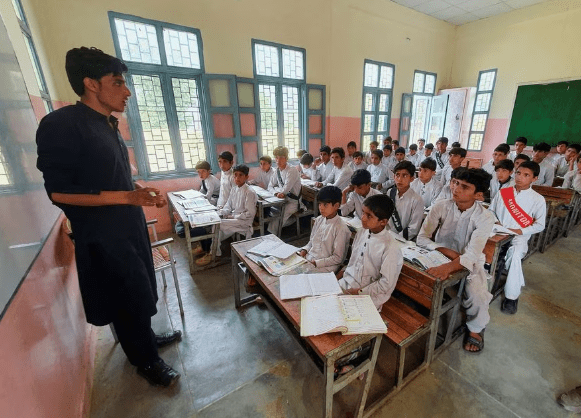

Ali Asghar Khan, the head teacher of Batungi Pashto High School, attributes the school’s high dropout rate to students’ lengthy journeys.

“Most boys who come from far-flung villages try their best to continue,” Khan added, “but they often face problems in traveling back and forth, either because they are too young, not strong enough, or sick, so they definitely abandon their studies.” “Dropout rates are quite high around these parts.”

In the rainy season, streams may become deadly rivers, and many pupils have to trek an hour or more each way to and from school, Khan added. Those who do make it report being drained by the ordeal, which is compounded by the scorching summers and frigid winters of northern Pakistan. They are sleepy and hungry, so it’s hard for them to focus, he added.

Throughout the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which is characterized by steep slopes plunging into valleys, communities have strung up dozens of cable car networks. They may shorten trips by 20 minutes for a low price, but even before Tuesday’s panic, they were already risky.

“Many accidents have occurred in the past,” claimed Naeem Khan, a former inspector general of the provincial police. “The locals, with the assistance of the police, tend to those who are stranded.”

A man who helped with the rescue on Tuesday said he had previously saved at least six people using smaller chairlifts.

A total of fifty charlifts may be seen throughout the Swat Valley hills. Many people have died or been injured in the previous year, but residents say the automobiles are a lifeline for students, particularly after last year’s devastating storm destroyed infrastructure.

Two months ago, when the cable car’s rope snapped, a mother and her kid plunged into the River Swat. Nasrullah Khan, a local neighbor, claimed, “We haven’t found their bodies yet.”

“WE EXPECT THIS”

The province’s challenges are felt across Pakistan, and local politicians and development organizations are working hard to find solutions.

Syed Hammad Haider, additional deputy commissioner of Battagram district, stated, “It is very difficult for them to reach schools in far-flung areas, but our government has in the last few years invested heavily and innovative ideas have been brought forward.”

All of the region’s cable cars are being inspected, and those that pose a safety concern will be shut down, he added; meantime, remote learning and community-based programs, especially for females, are a focus.

The World Bank has committed $300 million to improving educational opportunities in the province’s rural areas in a programme that will run until 2027.

World Bank spokesperson: “good all-weather roads, which are becoming increasingly vulnerable to natural disasters due to climate change,” are among the obstacles. Middle and high schools, particularly for females, are also in limited supply.

This is desperately needed for the children in war-torn districts like Battagram, who face danger just to attend school.

Another rescued kid, Rizwan Ullah, remarked, “We will now not go by lift, but I don’t want to leave school either.” All of these amenities, including roads, a bridge, and high schools, are desperately needed in our area. This is what we insist on.