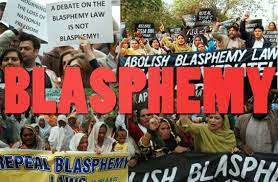

Beleaguered on many fronts and experiencing self-inflicted political and economic turmoil, Pakistan has added one more woe in the form of a hastily enacted law that makes for easier misuse of its notorious blasphemy law.

Although President Arif Alvi controversially returned the legislation that amends the blasphemy law passed by Senate – (his act of returning has been rebuffed by the caretaker government that took office recently) –, the debate that it has generated has already pitted the majority Sunni against Shia and other sects of Islam, while instilling fresh fear among the non-Muslims.

Passed before the National Assembly was dissolved on August 9, the legislation envisages that the punishment for blasphemy be increased from three years in prison to a whopping ten years apart from imposing a fine of PKRs one million. It also plans to change the offence from bailable to non-bailable.

While leaders of the other groups and human rights bodies have voiced opposition and concern, various Sunni groups and their spokespersons declined to respond to queries on the legislation. Simultaneously, some Sunni groups openly supported the bill, according to the weekly Friday Times (August 21, 2023) that sought to elicit opinion on the legislation.

“The contentious bill seeking enhancement of punishment for blasphemous and religious hate speech has picked at sectarian differences, drawing condemnation from religious scholars and civil rights bodies,” the weekly said.

Last week, Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ) leader Maulana Muhammad Ahmed Ludhianvi led a rally supporting the bill.

Pakistan has the world’s second-strictest blasphemy laws after Iran. About 1,500 Pakistanis have been charged with blasphemy over the past three decades. In a case covered by the international media, Junaid Hafeez, a university lecturer, was sentenced to death on the charge of insulting the prophet on Facebook in 2019. His sentence has been under appeal.

Although no executions have ever taken place, extrajudicial killings related to blasphemy have occurred in Pakistan. Since 1990, more than 70 people have been murdered by mobs and vigilantes over allegations of “insulting Islam.”

Like many other legal provisions, human rights activists and progressive quarters fear this could be misused and stoke sectarian differences.

They point out two glaring cases. One the murder of Salman Taseer by his own bodyguard after the former Punjab Governor called for the repeal or rationalising of blasphemy laws made most stringent during the Ziaul Haq regime. Convicted and hanged, the bodyguard became a cult with thousands visiting his tomb.

The other is the Christian mother of four, Asia Bibi, accused of blasphemy by fellow-farm workers, who remained in jail for nine years during her conviction that was overturned by the highest court. There were protests and threats when she was freed and was eventually whisked away to Canada.

An article by Ahmet T. Kuru in the Conversation, an Australia-based research and media outlet, “The politics of blasphemy: Why Pakistan and some other Muslim countries are passing new blasphemy laws,” states: “Of the 71 countries that criminalize blasphemy, 32 are majority Muslim. Punishment and enforcement of these laws vary.

Blasphemy is punishable by death in Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Brunei, Mauritania and Saudi Arabia. Among non-Muslim-majority countries, the harshest blasphemy laws are in Italy, where the maximum penalty is two years in prison.

Half of the world’s 49 Muslim-majority countries have additional laws banning apostasy, meaning people may be punished for leaving Islam. All countries with apostasy laws are Muslim-majority. Apostasy is often charged along with blasphemy.

Laws on apostasy are quite popular in some Muslim countries. According to a 2013 Pew survey, about 75% of respondents in Muslim-majority countries in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia favour making sharia, or Islamic law, the official law of the land. Among those who support sharia, around 25% in Southeast Asia, 50% in the Middle East and North Africa and 75% in South Asia say they support “executing those who leave Islam” – that is, they support laws punishing apostasy with death.” Kuru says that blasphemy laws historically emerged in the 12th century onwards as an alliance between the government and the religious authorities, both keen to curb any dissent and airing of new ideas. “They serve the political and religious authorities, and they continue to have a role in silencing dissent in many Muslim countries.” (Ends)