Pakistan is heading to the poll on February 8 to elect the members of the 16th National Assembly. As leading parties pace up election campaigns, the focus remains on the skyrocketing debt, inflation, and corruption issues. Amid the unprecedented economic turmoil, one pressing issue remains notably absent from most agendas: climate. With elections looming, Earth.Org takes a look at the main environmental issues Pakistan is facing and how a volatile national political scene is hindering efforts to properly address them.

—

Ranked 5th most vulnerable country to climate change on the Global Climate Risk Index, Pakistan faces countless pressing environmental issues that affect its economy and people, yet a complex mix of financial disorder and a looming market debt crisis have completely overshadowed them.

While the lack of a climate agenda in light of this week’s election is not surprising, the rapidly deteriorating climate crisis leaves Pakistan and the international community no choice but to step up mitigation and adaptation efforts to avoid irreversible consequences.

In August 2022, Pakistan made global headlines as unprecedented floods engulfed large areas of the country, bringing about devastation and affecting 33 million people, including 16 million children. Dubbed the “climate catastrophe of the decade,” the floods submerged one-third of the country, claiming 1,730 lives and displacing more than 12 million people.

With damages estimated at over US$30 billion and the loss of critical infrastructure, including thousands of schools and public health facilities, the floods severely worsened an already fragile economic situation – with external debt soaring to $125 billion and inflation reaching a record high of 38% – and deepened already existing inequalities, leaving millions of people vulnerable to food, energy, and financial insecurity.

Pakistan is no stranger to floods, especially in low-lying provinces such as Sindh and Punjab. In fact, its climate is commonly studied due to the country’s historically strong monsoon seasons, which can bring up to 70% of the annual rainfall in just a few months. However, the 2022 events were the most devastating in Pakistan’s 75-year history. Scientists blamed it on climate change.

“Things will not go back after the summer has passed. Here we have a problem of not just national but international climate governance and denialism about [climate change’s] actual ferocity and scale,” said then-minister for climate change Sherry Rehman in an interview with Channel NewsAsia.

In an analysis published a month after the floods, World Weather Attribution said climate change “likely increased extreme monsoon rainfall” that year, with several models and observations indicating that intense rainfall has become heavier as Pakistan warms. Indeed, during the 2022 monsoon season, Pakistan received more than three times its average rainfall in August, making it the wettest August since 1961, while Southern Sindh and Balochistan provinces received seven and eight times their usual monthly totals, respectively.

But floods are just one of the many extreme weather events Pakistan faces every year.

Severe droughts that have also plagued the country for decades are also becoming longer, more frequent, and more intense.

As climate change alters rainfall patterns, it does not just make monsoon seasons more intense but also more irregular and unpredictable. For a country that heavily relies on water from glacial melt and monsoon rains, variations in these water sources only increase its vulnerability.

For example, the 2022 floods followed months of record-breaking temperatures and exceptionally dry conditions. In March of that year, Pakistan received 62% less rainfall than normal and recorded the highest worldwide positive temperature anomaly during that month. And while heatwaves are not uncommon in the season preceding the monsoon, the very high temperatures so early in the year, coupled with a lack of rain, have led to extreme heat conditions, threatening public health and agricultural output.

The same occurred this winter, with Pakistan receiving lower-than-average rainfall, partially owing to the return of El Niño, a weather pattern associated with dried and warmer conditions in Southeast Asia.

“Our lives revolve around water. Two years ago, flash floods wreaked havoc on our farmland and crops, but now, the water for wheat cultivation is in short supply due to a lack of rainfall,” a 49-year-old mother of four living in southwestern Balochistan province told Deutsche Welle last month.

Once again, experts attributed these extremes to climate change, saying it has increased the probability of an event such as the 2022 heatwaves by a factor of about 30.

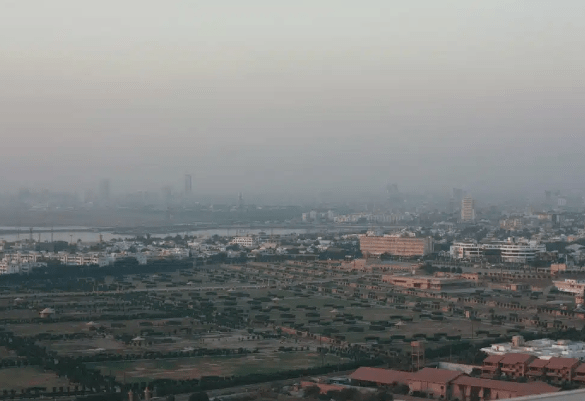

In recent years, several Pakistani cities have experienced alarming levels of air pollution. According to data from the World Air Quality Index (AQI), Lahore, Faisalabad, and Karachi are consistently ranked among the most polluted cities in the country. While these cities frequently exceed the World Health Organization’s (WHO) air quality guidelines, Air Quality Life Index (AQLI) data suggests that all of Pakistan’s 238 million people live in areas where the annual average particulate pollution level exceeds the WHO guideline, while 98.3% of the population lived in places where air pollution exceeds the country’s own safety standards.

In IQAir’s 2022 ranking of the world’s most polluted countries and regions, Pakistan ranked third, preceded only by Chad and Iraq. In terms of cities, most of the world’s 50 most polluted cities in 2022 were located in India and Pakistan. In that year, Pakistan’s capital city Lahore, home to more than 11 million people, was also named the world’s most polluted city, and it continues to be among the most polluted urban centres today.

Air pollution in Pakistan can be attributed to a combination of factors.

Currently, most of Pakistan’s energy comes from fossil fuels, with gas constituting the largest share, followed by oil and coal. Emissions stemming from fuel combustion account for more than 90% of the country’s total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and for 40% of overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with the transport sector contributing approximately 23% of these CO2 emissions.

Other major contributors to air pollution stem from industrial emissions from factories and power plants – which release pollutants such as sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter into the atmosphere, the agricultural sector – which is responsible for generating most of the methane and nitrous oxide emissions, and the burning of solid waste.

The effects of air pollution in Pakistan are far-reaching and detrimental to both human health and the environment.

High levels of air pollution have been linked to respiratory diseases, cardiovascular problems, and premature deaths. 2023 AQLI data suggests that people living in four South Asian nations – Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan – are expected to lose about five years of their lives on average because of air pollution. In Pakistan alone, over 22,000 people are estimated to die from outdoor air pollution, while another 28,000 deaths are attributable to indoor pollution. This is true particularly in low-income households which rely on biomass fuel such as wood, crop residues, and animal dung, for cooking, space heating, and lighting homes. While the share of people with access to clean fuels for cooking has doubled since the beginning of the century, more than 50% of the population still relies on polluting fuels.

The Pakistani government has taken steps to address the pressing issue of air pollution.

First of all, the country has set targets to progressively reduce its dependence on fossil fuels, in line with the 2015 Paris Agreement. In particular, Pakistan aims to cut 50% of its emissions while achieving a 60% share of renewable energy and 30% electric vehicles by 2030.

Moreover, in 2019, the government launched the National Clean Air Program (NCAP) in a bid to cut air pollution levels through improved industrial emissions standards, the promotion of cleaner transportation, and the enhancement of monitoring and enforcement. It has also introduced several policies to encourage the use of cleaner fuels such as compressed natural gas (CNG) in vehicles.

In 2022, the Ministry of the Environment launched a National Clean Air Plan with support from the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC), the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), and Clean Air Asia, which “sets targets for air pollution concentration, identifies actions to mitigate air pollution, and outlines a plan for coordinating action on air quality management.” As part of the initiative, the country carried out its first national air pollutant inventory to quantify air pollutants at national and provincial level, which helped identify the main culprits of air pollution and outline a strategy to improve these sectors, including cooking and heating, vehicles, certain agricultural practices, and the open burning of waste.

Although the government’s acknowledgment of the issue is evident, the success of these initiatives has been limited, with pollution levels still on the rise owing mostly to challenges in enforcement, implementation, lack of adequate resources, and poor coordination.

According to the World Bank, Pakistan is one of the most water-stressed places in the world, behind only six other countries, and, given its large population – Pakistan is the world’s sixth most populous country – water availability per person is comparatively low. It is estimated that Pakistan’s water availability per capita has decreased from 5,260 cubic meters in 1951 to about 1,000 cubic meters in recent years, indicating a severe water scarcity situation. This data suggests that the country is quickly approaching the “water stress line.” The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) estimates that by 2025, Pakistan could be in a situation of absolute water scarcity, where there is not enough water to meet basic needs.

According to a report by the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR), about 60% of Pakistan’s population lacks access to safe drinking water, and 30% of all diseases as well as 40% of all deaths are attributable to poor water quality. Women and children are particularly vulnerable, especially in rural areas where sanitation is particularly inadequate, and most supplies are contaminated. The WHO estimates that about 55,000 children under the age of five die each year in Pakistan due to waterborne diseases like diarrhoea, cholera, and typhoid.

Many factors contribute to elevated water pollution levels in the country, from the lack of a comprehensive sewerage system in cities and inadequate sanitation infrastructure, to poor waste management and the excessive use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and untreated industrial effluents.

A lack of efficient water management systems is also to blame. According to the Indus River System Authority (IRSA), Pakistan receives approximately 145 million acre-feet (MAF) of water every year but is only capable of storing 13.7 MAF. Similarly, the country also lacks sufficient storage capacity to capture and store water during periods of high rainfall, effectively losing significant amounts of water during the frequent monsoon seasons.

Moreover, natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes can disrupt water supply systems, causing contamination and further exacerbating the issue. In particular, stagnant water constitutes the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, facilitating and accelerating the spread of malaria and dengue.

In the aftermath of the 2022 floods, the country entered a “second wave of death and destruction” as standing waters provided ample opportunity for mosquitoes to breed and spread infectious diseases. The country saw at least a four-fold increase in the reported number of malaria cases after the floods, from 400,000 cases nationwide in 2021 to more than 1.6 million cases in 2022.

The rapidly changing climate and melting of glaciers are further exacerbating the issue, with the Indus River, the country’s primary source of water for agriculture, industry, and domestic use, particularly at risk.

The river heavily relies on the meltwater from the Himalayan glaciers. According to a study published in the journal Nature, the Indus Basin glaciers have been losing mass at an average rate of about 20 centimeters per year since the 1990s. This loss of glacial ice reduces the amount of water flowing into the river system, affecting water availability downstream. A report by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) mentions that the flow of the Indus River could decrease by up to 40% in the coming decades due to glacial retreat. This reduction in river flow affects irrigation for agriculture and availability of water for other sectors.

Agriculture, which contributes about one-fifth of the national gross domestic product (GDP), is one of the sectors contributing the most to water insecurity. According to the Pakistan Water Partnership, around 90% of the country’s water resources are utilized for agriculture. As glaciers shrink, the availability of this water source decreases, posing risks to agricultural productivity and food security.

But this is not the only issue affecting the sector. Inadequate infrastructure and outdated irrigation methods result in inefficient water management practices. The canal system, used for irrigation in agriculture, suffers from high water losses due to seepage and evaporation. Moreover, the over-extraction of groundwater, primarily for agriculture, has led to a decline in water tables in many parts of Pakistan. This over-dependence on groundwater contributes to water scarcity and can lead to land subsidence and soil degradation.

To address the situation, the Pakistani government has implemented several initiatives aimed at improving water management by enhancing water infrastructure and promoting conservation practices.

For instance, in 2018, Pakistan introduced a National Water Policy to guide water resource management and development. The policy focuses on improving water governance, enhancing infrastructure, promoting conservation, and addressing water-related challenges. The government has also launched several public awareness campaigns to promote water conservation practices, such as efficient irrigation techniques, rainwater harvesting, and reducing water wastage in domestic and industrial sectors, and has ordered the construction of reservoirs and dams such as the Diamer-Bhasha Dam and the Dasu Dam, key infrastructure to enhance water storage capacity and manage water resources effectively.

The Diamer-Basha dam, currently still in preliminary stages of construction, is expected to have an 892 feet-high spillway, 14 gates, and will be capable of holding 6.4 MAF alone. And yet, as life changing as its construction would be for the people of Pakistan, the associated cost is equivalent to nearly 10% of Pakistan’s total GDP. Moreover, the project has been at the centre of controversies, as local communities warned it could affect the region’s social, economic and ecological balance in the region and would inundate 32 villages of the Diamer district in Northern Areas, rendering thousands of people homeless.

Despite the good intentions, the precarious economic status of the country has often hindered the success of these measures. For this reason, Pakistan has sought international assistance and cooperation to address water scarcity, for example by engaging in dialogues with neighbouring India and Afghanistan to collaborate on transboundary water management and establish water-sharing agreements. These, however, have been the subject of controversy over the years.

For example, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), an agreement between India and Pakistan that governs the distribution of water from the Indus River and its tributaries between the two countries, has been a source of contentions and disputes since its signing in 1960.

One area of dispute centres around the construction of hydropower projects by India on the rivers allocated to it under the treaty, particularly the Chenab River, with Pakistan raising concerns about the potential impact of these projects on its water supply and agricultural activities. The country has also expressed concerns about India’s water management practices and has accused it of violating the treaty by using more water than allowed for irrigation purposes, arguing that this affects the flow of water downstream and impacts water availability in the country

Food insecurity is a significant challenge in Pakistan, with a considerable number of people lacking reliable access to nutritious and sufficient food. In the Global Hunger Index 2021, Pakistan ranked 92nd out of 116 countries in terms of food security. While the exact number of food-insecure individuals is difficult to determine accurately, it is estimated that around 40% of the population experiences food insecurity to some extent.

Climate change is a significant contributor to food insecurity in Pakistan. The country is highly vulnerable to climate-related risks, and the changing weather patterns have adverse effects on agricultural productivity, water availability, and natural resources, with estimates suggesting that climate change will contribute to an 8-10% drop in agricultural productivity between now and 2040. This is particularly true for wheat and rice crops, which will experience a 6% and a 15-18% drop, respectively.

There are many ways in which climate change contributes to lower agricultural output and food insecurity. For a starter, altered rainfall patterns, including irregular and unpredictable rainfall, affect crop growth, leading to reduced yields and crop failures. Inconsistent rainfall also makes it challenging for farmers to plan their agricultural activities and hampers the overall productivity of the agricultural sector.

The increase in the frequency and intensity of floods, particularly in northern Pakistan, has also significantly affected the country’s main crops – wheat, rice, cotton, sugarcane, and maize – submerging fields and washing away fertile soil.

What’s more, rising temperatures also create favourable conditions for the proliferation of pests, insects, and diseases, not only among humans but also crops. Rising temperatures and altered weather patterns affect the timing and intensity of pest outbreaks, leading to crop damage and increased reliance on pesticides.

The issue became of even greater concern following the extraordinary 2022 monsoon season, with nearly 5.7 million people including 3.4 million children affected by food insecurity. The exceptional rain the country witnessed that year has had a devastating impact on Pakistan’s agricultural sector, which employs 39% of the country’s workforce, with farmers caught off guard and unable to protect their crops from floodwaters.

The latter destroyed about 6.5 million acres (2.6 million hectares) of cropland nationwide, amounting to US$3.7 billion in damages and long-term economic losses of nearly US$10 billion for the agriculture, food, livestock and fisheries sectors. In the hard-hit Sindh province alone, only 700,000 acres (282,000 hectares) of the 4.3 million acres (1.7 million hectares) under cultivation survived the floods. The lack of a comprehensive crop insurance policy in the country left most of the country’s farmers without financial support.

Making matters worse, in the months following the floods, rural communities across the country experienced a 50% increase in food prices compared to the previous year, putting many already scarce staples out of the reach of the low-income communities.

A combination of high food prices, frequent climate shocks, widespread livestock diseases, and reduced food production put an estimated 11.8 million people at risk of experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity between November 2023 and January 2024, according to a the recent Acute Food Insecurity Snapshot published by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC).

Rapid urbanisation and population growth have led to an increase in waste generation in Pakistan, with World Bank figures suggesting the country generates approximately 48.5 million tons of solid waste annually, with an estimated 20 million tons in urban areas alone.

Unprecedented levels of waste generation have left the government unable to properly manage it. The inadequate waste management infrastructure and lack of proper waste collection, segregation, and disposal systems have contributed to the accumulation of waste in public spaces, rivers, and open areas and has made burning and dumping of garbage common practices.

The majority of solid waste generated in the country is disposed of in an uncontrolled manner, causing pollution of land and water bodies. Indeed, dumped or burnt waste releases toxic gases such as carbon monoxide (CO), particulate matter, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that significantly contribute to air pollution.

According to a 2023 UN Habitat report, these habits are to blame on deeply-rooted unsustainable production and consumption practices, inadequate solid waste management infrastructure, deficient legal and policy frameworks, weak enforcement mechanisms, and limited financial resources at national and local levels.

The country also ranks as the sixth globally and third in Asia among plastic waste generators, with an estimated 5-10% of all its municipal solid waste being plastic, and it is among the top 10 contributors to marine plastic pollution globally, with an estimated 55 billion pieces of plastic waste generated annually.

To address the waste pollution crisis, the Pakistani government has initiated various measures. The introduction of waste management policies, such as the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act, aims to regulate waste disposal and promote recycling. Efforts are also being made to improve waste collection and segregation systems, establish waste treatment plants, and create awareness about the importance of waste management and recycling among the public. However, significant challenges remain, including the need for infrastructure development, capacity building, and effective implementation of waste management strategies. Collaboration between the government, private sector, and civil society is crucial to tackling the waste pollution crisis and moving towards a more sustainable and cleaner environment in Pakistan.