Sign up for the View from Westminster email for expert analysis straight to your inbox Get our free View from Westminster email Please enter a valid email address Please enter a valid email address SIGN UP I would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our privacy notice Thanks for signing up to the

View from Westminster email {{ #verifyErrors }}{{ message }}{{ /verifyErrors }}{{ ^verifyErrors }}Something went wrong. Please try again later{{ /verifyErrors }}

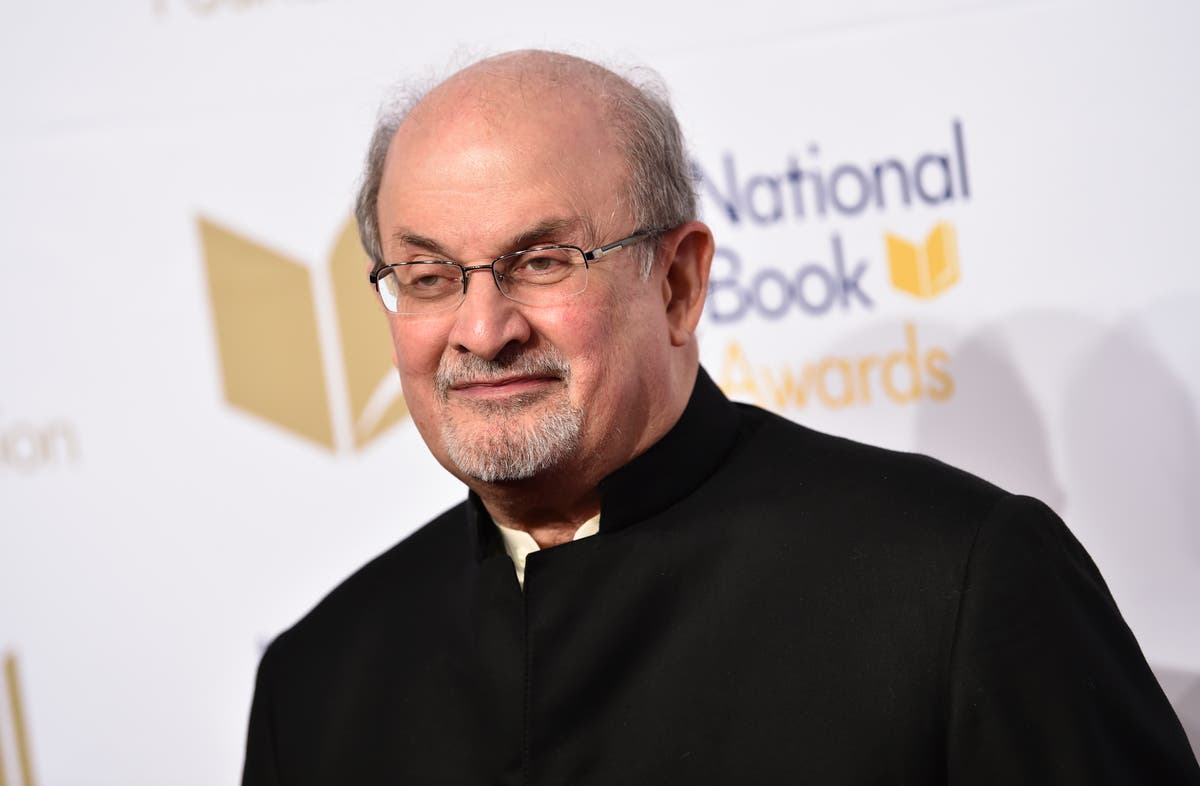

Bashing Islam. I’ve been accused of that before by people I used to pray side-by-side with for years. But that’s not why I’m writing about Salman Rushdie’s stabbing and how I was taught to hate him from a young age. Instead, I want to show how easily people in my position can be taught to hate someone they don’t even know.

I attended a private Islamic school inside the US for six years. Salman Rushdie was universally reviled in my classes. One Islamic Studies instructor in particular spoke about him regularly. Rushdie was considered an “apostate” by some since he was born into a Muslim family yet didn’t practice the religion. He was hated by others for suggesting — even in a fictional piece of work — that the Prophet Muhammad’s (peace and blessings be upon him) message wasn’t the absolute, infallible message of a one true God. If you don’t believe that, then you aren’t Muslim, end of discussion: that’s what we were taught. And, according to many rulings from Islamic governments, apostates should be killed.

Over the years, I found myself hating Rushdie, too. The author had had a fatwa issued against him by the Ayatollah Khomeini when I was three years old, when my friends and I were more interested in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and begging our parents for an extra five minutes at the playground. But that didn’t matter. We despised him.

I’m not saying entire lectures were dedicated to Rushdie’s heretic work in my school, but his name popped up in conversations about Islam often. Whenever a discussion about certain Quranic teachings or references to “enemies of Islam” came up, so would he.

I grew up in a time where men with names that sounded like mine (and my middle and high-school friends’) were always the bad guys. On TV, a terrorist was depicted prostrating in prayer on a mat only moments after brandishing a gun on a plane, threatening women and children in the middle of a hijacking. I saw this and I was insulted. We weren’t like these violent people onscreen; these were extremists we were getting lumped together with, and everyone who believed we were like those animals on camera were complete fools.

But when you’ve been looked at as the “bad guy” for that long, you start to get into the politics of subjugation. For me, it happened as early as 12 years old. Of course I didn’t condone suicide bombings and hijackings, but I’d immediately argue that these murderers were probably “pushed to that point” because they were being “forced” into that position by global politics that left them no other option.

That’s the same type of thinking that convinced me to hate a man I didn’t even know. I didn’t read The Satanic Verses — I didn’t even know who the Ayatollah Khomeini was, except that he was referenced in a Back to the Future movie and Sebastian Bach once called him out onstage at a concert, because I happened to see it on VH1. But Rushdie was the enemy, and when I got to college and finally took a look at the controversial book as an aspiring writer myself, I was instantly critical. I downplayed his work, chalked all the controversy up to him being a shock jock.

Ironically, I came to appreciate Rushdie’s writing when I decided to focus more on an aspect of Islam that isn’t discussed enough, and it’s the idea that each person is their own sheikh. There’s an ayah (verse) in the Quran that’s repeated so many times: “Allah is the best of judges.” It urges Muslims to not follow one particular school of thought, but instead to stay true to the Quran — an idea that many Islamic scholars still espouse today.

I stopped looking at people who were critical of Islam, like Rushdie was perceived to be, as “boogeymen” meant to be hated. The truth is that Rushdie has been vocally against global policies that are widely considered destructive to the Middle East, which is 85 percent Muslim. But even if he hadn’t been, what good did it do for me to hate him? He was just a man who published a book. That sounds simple, but when I first came to that thought during my college days, it felt like an epiphany. Hating Salman Rushdie was pointless.

The man who has been arrested for the attempted murder of Rushdie, Hadi Matar, comes from a town eight miles away from the New Jersey school I attended. At 24 years old, he was born long after the fatwa against Rushdie was issued. It seems clear that he hates Rushdie, like I once did. I’d also be willing to bet that he knows as little about his books, and about the Ayatollah Khomeini, as I did at that age.

Although reports indicate that Matar was supportive of Shia extremism and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps on social media, Matar is ethnically Lebanese, and Lebanon is a full 1,300 miles from Iran. He lives in Fairview, New Jersey. He is the living embodiment of how far-reaching hatred can be.

His is a mentality I understand, but subscribing to it is a choice, and something that Muhammad, according to lifelong devoted Islamic scholars, wouldn’t condone. In fact, there are numerous documented instances in the history of the Prophet’s life where he didn’t take action against those who offended or disrespected him.

That hasn’t stopped a large number of other imams and scholars who have condoned attacking or even killing people who are seen to have insulted the Prophet Muhammad. And unfortunately, these wrongful ideologies are often instilled in people from youth. They were with me.