Riyadh consultations hosted by Saudi Arabia have been boycotted by the Houthis, leaving little chance of success.

Hodeidah, Yemen – Attiyah Dahfash has spent more than three years internally displaced as a result of the war in Yemen.

The 48-year-old was the head teacher of the only government-run school in al-Ko’ea, a hamlet south of Yemen’s Red Sea port city of Hodeidah. The hamlet was largely made up of Dahfash’s own extended family, and he and his family were able to live a relatively quiet life tending to their livestock and beehives.

However, like many Yemenis, Dahfash’s life has been upended by the war in his country.

Along with his three elder brothers and their families, Dahfash was forced to abandon his rural life and flee when fighting between Iran-allied Houthi rebels and Saudi-led coalition-backed forces arrived in al-Ko’ea in mid-2017.

According to Dahfash, by August 2018, the fighting had led to the deaths of 33 members of his family, mostly women and children, forcing the rest to flee.

“More than three years into our displacement and we are unable to return to our homes,” Dahfash told Al Jazeera from his new home in the capital, Sanaa. “We are unable to see or get together with our family members, who are all displaced in different areas.”

Dahfash left al-Ko’ea a few months before the Stockholm Agreement was signed by Yemen’s warring parties in December 2018.

The deal stopped an offensive by the Joint Forces, a Saudi-led coalition backed group, to take Houthi-held Hodeidah city, which is a major port of entry for food, goods and oil.

The United Nations feared that a continuation of the fighting in Hodeidah would lead to famine in Yemen.

Yet, despite the Stockholm Agreement, fighting continued in Hodeidah, meaning that a return to al-Ko’ea was not safe for Dahfash or his family.

The situation highlighted how the Stockholm Agreement was never fully implemented, despite the international community’s best wishes.

Fighters from both sides were never redeployed as agreed, and hostilities never actually ceased, particularly in the southern districts of Hodeidah governorate.

The fight for Hodeidah has left hundreds of people dead and injured, and drove thousands of families from their homes. Even though coalition-backed forces have now withdrawn from Hodeidah city and its environs, the city’s eastern and southern outskirts are still infested with landmines.

Riyadh Consultations

An end to the Yemeni conflict might eventually allow Dahfash and his family to return home.

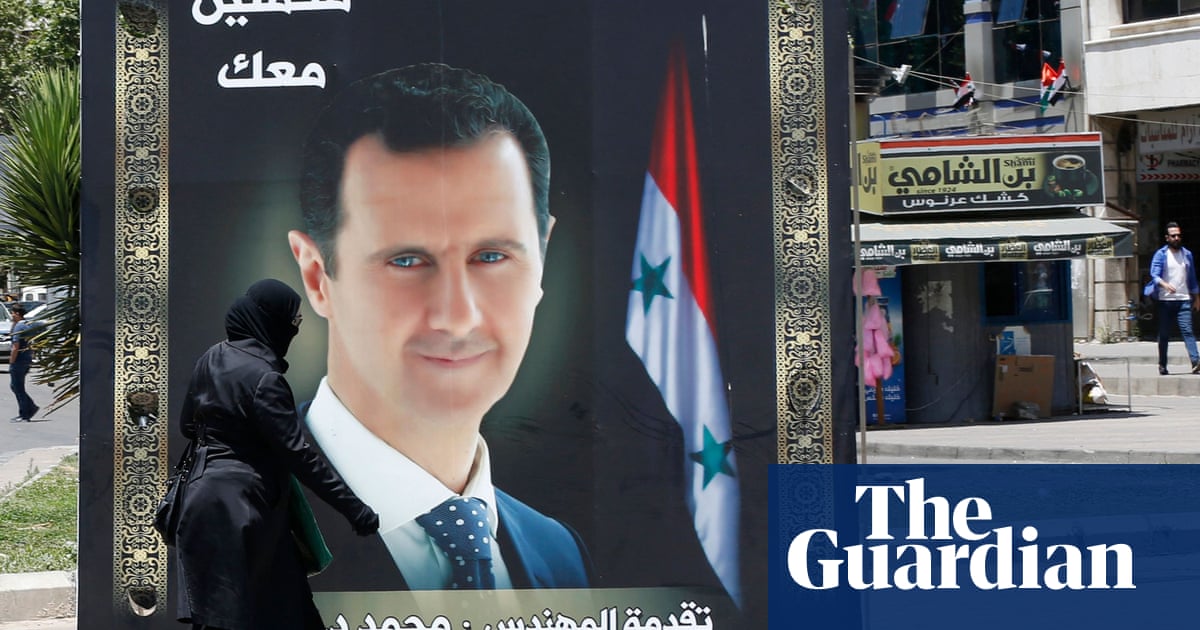

A weeklong round of consultations kicked off in Saudi Arabia’s capital, Riyadh, on Tuesday, with that goal in mind. But it had one major problem – the absence of the Houthis, who control the majority of Yemen’s major population centres.

The Houthis were invited, but rejected the invitation from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and said they would instead welcome talks with the Saudi-led coalition at a neutral venue, including in other Gulf states.

“It is neither logical, nor fair that the host of the talks is also the sponsor of war and blockade,” the Houthi movement said in a statement published on their official news agency.

Instead, the Houthis stepped up their own missile and drone attacks on several areas in Saudi Arabia, including one last Friday near a Jeddah racetrack that was hosting Formula One motor racing, before announcing a three-day unilateral ceasefire on Saturday.

The Saudi-led coalition then announced its own 30-day halt to military operations on Wednesday, which followed a UN call for a truce during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

However, in a statement released on Wednesday, the Houthis’ Supreme Political Council said that if Saudi Arabia did not agree to end its air raids and blockade of Houthi-controlled ports, it would continue to fight.

“The Yemeni leadership and people will retain their full right to take whatever political and military steps it deems appropriate in a manner that guarantees their legitimate rights,” the statement said.

With unilateral ceasefires declared by both Saudi Arabia and the Houthis, and with no positive response from each side, peace for Yemenis appears to be hanging by a thread.

“The Riyadh talks are an attempt by the Saudi government to achieve its own objectives, rather than the objective of peace for Yemenis,” Abdulghani al-Iryani, a senior researcher at the Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, told Al Jazeera.

“It may result in some kind of consensus among anti-Houthi forces, which would probably reduce the superiority of the Houthis on the battlefront, and, therefore, create the necessary balance that would make a cessation of hostilities possible,” he added.

However, in al-Iryani’s opinion, that was the most that could be hoped for out of the Riyadh talks.

For Dahfash and his family, that may mean a prolonged stay away from their homes in al-Ko’ea.

“It has been eight years of war now; my family members are still scattered in different places,” Dahfash said. “We are so exhausted, and just hope that the war will end some day, and we can return safe to our hometown.”