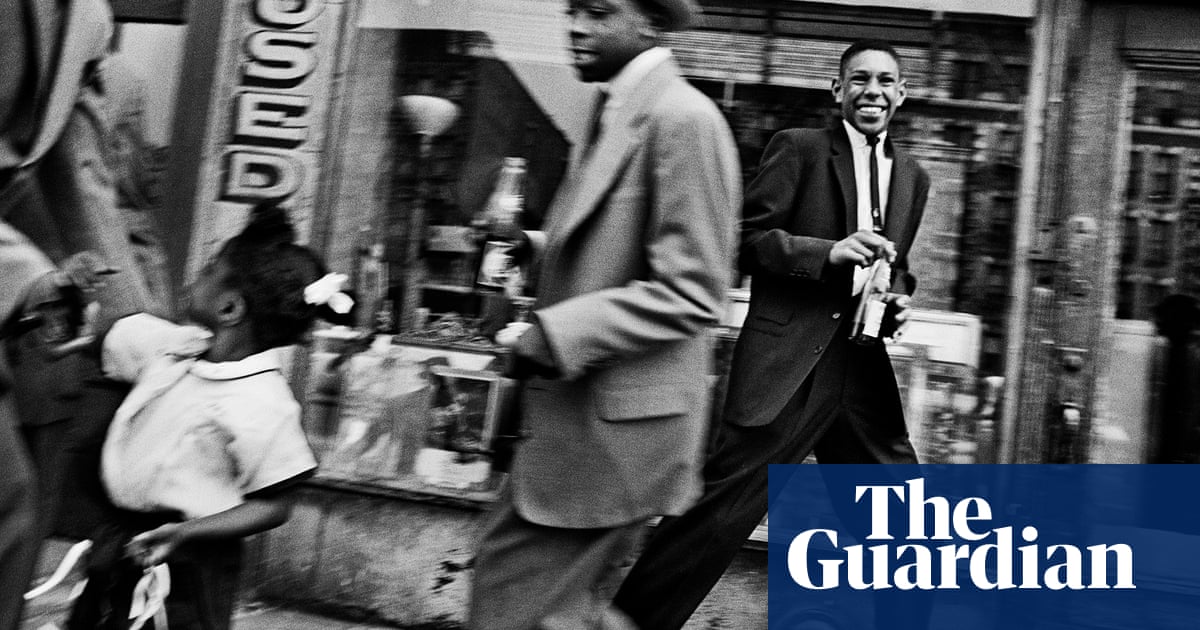

‘I photograph what I see in front of me,” declared William Klein, who has died aged 96. “I move in close to see better and use a wide-angle lens to get as much as possible in the frame.” Uncompromising, ambitious and to the point, the words are characteristic of this American photographer and film-maker, who pulled no punches in his first publication, Life Is Good and Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (1956).

The book’s title was a mouthful of Madison Avenue mixed with the Daily News. Klein presented a grainy, grimy and claustrophobic New York: a sea of faces in a shabby city, with open mouths, wide eyes, big grins and furrowed brows. Klein saw the book “as a tabloid gone berserk, gross, over-inked, brutal layout, bull-horn headlines. This is what New York deserved and would get.”

Eschewing any pretext of being the unassuming observer, he pushed to the front and pointed his finger. The photographs are a cacophony of black and white, a blizzard of charcoal grain and smudged grey shapes, veering between the formal and the fuzzy, driven by chance and chaos. Neon signs, billboards, concrete and tarmac, all pressed together in the photographic frame to give the impression of a city squashed under a shoe – Klein’s shoe.

Antonia and Yellow Taxi, New York, 1962, by William Klein. Photograph: William Klein/Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Living in Paris from 1948, he came to photography from his early studies in art. He had enrolled at the Sorbonne to take up a course in history of art and studied painting with Fernand Léger, whose background in cubism and futurism, and development of what became pop art, had a profound influence on Klein. Léger’s statement that he wanted “to paint in slang with all its colour and mobility” forms a close parallel to the street-savvy photography that became one of Klein’s hallmarks.

Klein painted in a geometric abstract style, later producing murals and kinetic art (art that incorporates motion). To break free from what he called “the same old paintings of circles, squares and triangles”, he used his kinetic art to make photograms – traces of light on photographic paper.

Working in Milan, he produced a series of quasi-abstract photography covers for the architectural magazine Domus, which brought his work to the attention of Alexander Liberman, the art director of American Vogue. Klein had been experimenting with a Rolleiflex camera; not in the studio but, as he put it, “out looting the streets”. Liberman perceived a brutal, graphic quality to Klein’s photographs that he believed would have a perverse beauty in the glossy magazine.

Liberman enticed Klein back to New York in 1954 with the offer of a contract as a Vogue fashion photographer and the funding to do his own photographic project. Klein chose to photograph his native city. “I had a peculiar kind of double vision, one eye almost Parisian, the other an incorrigible wise-ass New Yorker. I realised that whatever culture shock I felt would wear off eventually, so I went to town and photographed non-stop, with, literally, a vengeance.”

No American publisher would touch the resulting book, Life Is Good and Good for You in New York. According to Klein, “Everyone I showed it to said ‘Ech! This isn’t New York – too ugly, too seedy, too one-sided … This isn’t photography, this is shit.’”

William Klein in Paris, 2016. ‘I had a peculiar kind of double vision, one eye almost Parisian, the other an incorrigible wise-ass New Yorker,’ he said. Photograph: Zhong Weixing/AP

Eventually he took it to Paris, where he showed it to the film-maker Chris Marker, who was then working for the publisher Editions du Seuil, producing Petite Planète, a series of pocket travel books. Overcoming their objections, Marker persuaded Editions du Seuil to publish the book in 1956. It won the Prix Nadar award for best photography book edited in France.

Klein, for all the hype, was not inventing a new form of photography. His talent was to appropriate a certain form of it – a particularly brash, graphic approach to documentary photography – and apply it into a format usually reserved for the sedate monograph.

Liberman was shrewd to spot this, and Klein’s fashion shoots for Vogue, for which he worked for a decade from 1955, ushered in a new look to distinguish it from the era of photographers such as Cecil Beaton.

Klein was, in fact, following in the footsteps of Weegee, the celebrated crime photographer, and Lisette Model, whose caustic photographs of bathers in Coney Island also inspired Diane Arbus. In turn, Klein’s aggressive style influenced the Magnum photographers Martin Parr and Bruce Gilden.

Nina and Simone, Piazza di Spagna, Rome, 1960, by William Klein. Photograph: William Klein/ Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

But Klein’s New York work always suffered from being compared with Robert Frank’s The Americans, which was published shortly afterwards. Frank’s quieter, more introspective photographs earned him a place at the high table of American photography, whereas Klein’s loud voice saw the prophet sidelined in his homeland.

Drawn to cinema as much as photography, he went to Italy to work as an assistant to Federico Fellini on Le Notti di Cabiria (Nights of Cabiria, 1957), published a book of photos of Rome (1959), and followed this with further city photo books, Moscow (1964) and Tokyo (1964).

He returned to New York to make Broadway By Light (1958), a bold, visually graphic film of Broadway’s neon blackboard that Klein claimed was the first pop art film. Back in Paris, he worked as an artistic consultant on Zazie dans le Métro (1960), directed by Louis Malle.

He made a documentary for French television on the photographer Richard Avedon and the model Suzy Parker, and another about voting behaviour in a referendum, which was pulled, hours before transmission, by the French ministry of information. These joint experiences led to his film Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), ridiculing the fashion industry and the business of television.

Klein decided to make a film on Muhammad Ali and, in 1964, flew to Miami for the fight between Ali (then still Cassius Clay) and Sonny Liston. He saw Malcolm X sitting on his own on the plane and took a seat beside him. By the time they landed, his new friend had guaranteed Klein great access to film Ali. (“Malcolm spread the word that I was all right. I could do anything I wanted.”) He later combined the resulting short, Cassius le Grand (1964), with his footage of Ali’s 1974 triumph over George Foreman in the rumble in the jungle in Zaire for a two-stage documentary, Muhammad Ali: The Greatest, released in 1975.

Watchman, Cinecittà, Rome, 1956, by William Klein. Photograph: William Klein/Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Klein continued making films, mainly satirical documentaries, through to the end of the century. In the 1980s, he resumed his closeup, high-contrast black-and-white photography, and would present these elegantly shrill prints framed with the thick, red marks of a chinagraph pencil.

In some respects, Klein was an outsider all his life. A year after his birth, his parents, who were Jewish immigrants, lost their clothing business in the Wall Street crash.

A precocious student, Klein graduated from high school three years early and studied sociology at City College, New York. He joined the army in 1945 and was posted to Germany, where he worked as a cartoonist on the Stars and Stripes newspaper, then moved to Paris, making the city his home for much of the rest of his life.

He married Jeanne Florin in 1948, having met her on his second day in Paris. She died in 2005. Klein is survived by their son, Pierre, and his sister Caryl.

• William Klein, photographer and film-maker, born 19 April 1926; died 10 September 2022