Sign up for the View from Westminster email for expert analysis straight to your inbox Get our free View from Westminster email Please enter a valid email address Please enter a valid email address SIGN UP I would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our privacy notice Thanks for signing up to the

View from Westminster email {{ #verifyErrors }}{{ message }}{{ /verifyErrors }}{{ ^verifyErrors }}Something went wrong. Please try again later{{ /verifyErrors }}

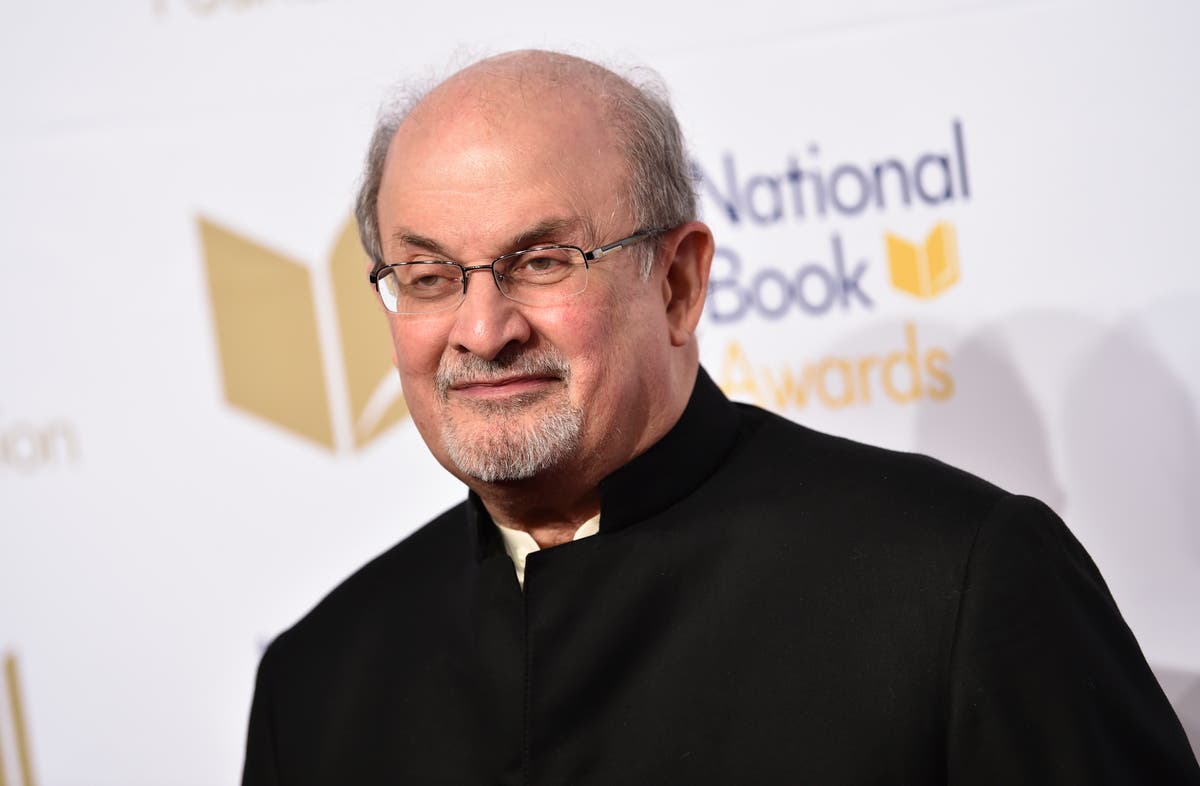

The vicious attack on Sir Salman Rushdie serves as a timely reminder that British Muslims also face threats from extremists who want to limit free speech in the public domain.

The stabbing of Rushdie, who was accused of blasphemy by some Muslims over his book, has thrust the threat of violent Islamist extremism back into the spotlight. Such fundamentalists have actively targeted supposedly “heretical” Muslims who are considered “un-Islamic” due to their support for western liberal democratic freedoms, along with ex-Muslims, who are viewed as apostates.

The suspect behind the attack, Hadi Mater, is a 24-year-old California-born man of Lebanese origin. His social media activity suggests he is sympathetic to religious fundamentalism and supportive of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

There are well-intentioned progressive liberals who may be reluctant to wade in over the stabbing of Rushdie – fearful of being accused of Islamophobia if they draw attention to its potential ideological motivations. But this kind of political correctness has become a form of an alliance with political Islamists who portray our country as fundamentally “Islamophobic” (a recent study found that three in four British Muslims believe Britain is a good place to live as a Muslim).

More importantly, it is worth noting that 63 per cent of British Muslim respondents in the study reported being worried about the threat of Islamist extremism – not far from the 67 per cent for the wider general population.

The mistake is in treating British Muslims as a monolithic single-voice bloc. British Muslims who have expressed solidarity with Sir Salman Rushdie, such as counter-extremism expert Wasiq Wasiq, have been called a “munafiq” (“false Muslim”) and “lapdog” by other Muslims.

Anti-Islamist British Muslims rely on our freedoms and civil liberties to challenge orthodox hierarchical structures; they would be disempowered by the expansion of censorship that came with the calls to ban Salman Rushdie and his books. Introducing more censorious measures will only undermine our freedom of expression and empower those who support tight restrictions.

This is why I took issue with the APPG British Muslims’ working definition of Islamophobia, which at times conflated genuine anti-Muslim prejudice with perfectly reasonable criticism of orthodox religious doctrines. Leading anti-FGM and women’s rights campaigner Nimco Ali argued that the working definition would leave secular and feminist Muslim women vulnerable to being slandered as Islamophobic, as they seek to uphold the basic human rights and freedoms of women who question male-dominant interpretations of religious texts.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

It is absolutely essential that anti-Muslim hatred and prejudice, which directly impacts the wellbeing of British Muslims, is addressed. This includes anti-Muslim acts of hatred and violence – something we must take seriously when one considers that far-right extremism is the fastest-growing terror threat in the UK. More also needs to be done to tackle anti-Muslim prejudice in the UK labour market and the private rented housing sector.

But the attack on Salman Rushdie reminds us that we must not cave in to those who wish for their religious and political sensitivities to be prioritised over the cornerstones of liberal democracy.

Britain is free of blasphemy laws and it should remain that way; we should stridently push against organisations who want to bring them back. As a society, we ought to be wary of those who wish to restrict free speech in order to marginalise and silence their co-religionists who are critical of norms and practices within British Muslim communities.

Dr Rakib Ehsan is an expert in the social integration of British ethnic and religious minorities