In a world where scientific breakthroughs have transformed once-deadly diseases into manageable or even eradicated threats, it is a grim irony that rabies — a fully preventable and treatable disease — continues to claim lives in Pakistan, even in 2025.

Despite global progress, Pakistan remains trapped in a vicious cycle of neglect, misinformation, and institutional apathy when it comes to addressing one of its deadliest public health crises.

Every year, thousands of Pakistanis are bitten by stray dogs, yet timely access to life-saving vaccines and treatment remains elusive for much of the population.

Rabies, nearly always fatal once symptoms appear, could be prevented with simple interventions.

But year after year, the disease continues its silent rampage, killing with a brutality that reflects not just a medical failure but a deeper societal one.

The statistics are harrowing. According to health experts, Pakistan records thousands of rabies deaths annually — a figure that is likely underreported due to gaps in healthcare data and limited surveillance mechanisms.

Most victims are children, many from rural and impoverished communities, who never receive the critical post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) needed to survive.

In some hospitals, even in major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Quetta, shortages of the rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin — both essential for treatment — are chronic and deadly.

The persistence of rabies as a public health emergency in Pakistan cannot be explained solely by a lack of resources.

Rather, it points to a lethal combination of government inaction, poor public health infrastructure, and widespread ignorance about the disease.

In many rural areas, traditional healers and home remedies are still relied upon to treat dog bites, often with tragic results.

Meanwhile, public awareness campaigns are virtually non-existent, and dog population control measures remain sporadic, poorly funded, and often inhumane.

Municipal negligence is another key factor exacerbating the crisis.

Stray dogs roam freely across urban and rural landscapes, with little to no coordinated effort to manage their population through vaccination drives or sterilisation programmes.

Attempts to deal with the stray dog population often take the form of ad hoc, brutal culling campaigns — efforts that are both ethically questionable and scientifically ineffective.

Without comprehensive vaccination programmes for both animals and humans, Pakistan remains caught in an endless cycle where new generations of stray dogs and new human victims are inevitable.

The situation has been further compounded by the broader fragility of Pakistan’s healthcare system.

Chronic underfunding, lack of trained personnel, logistical hurdles, and political instability have long hampered efforts to build resilient public health programmes.

Rabies, being a disease that primarily affects the marginalised and voiceless, receives even less attention compared to more high-profile illnesses like dengue, polio, or hepatitis.

For successive governments, it has remained a low priority — a public health crisis hidden in plain sight.

At the heart of this tragedy is a profound inequity.

Access to life-saving rabies vaccines and post-bite care is heavily skewed toward urban centres, and even there, it is far from guaranteed.

In rural Pakistan — home to a significant portion of the country’s population — the situation is far worse.

Clinics are often ill-equipped, doctors untrained, and patients left to rely on chance or charity.

Victims of rabid dog bites may have to travel hundreds of kilometres to reach a facility that can administer proper treatment — a journey that many do not survive.

The story of rabies in Pakistan is also a story of lost childhoods, broken families, and needless deaths.

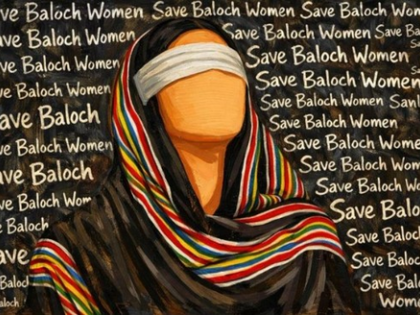

In the villages of Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan, countless stories circulate of young boys and girls bitten while playing, herding animals, or walking to school — and succumbing days or weeks later to one of the most horrific deaths imaginable.

Rabies is not a quiet killer. It is a disease that brings terrifying neurological symptoms: hydrophobia, hallucinations, violent spasms, and ultimately, death.

It is a death that leaves an indelible mark on families and communities, breeding fear and grief in its wake.

Despite mounting evidence and repeated calls from health experts, international organisations, and civil society groups, Pakistan’s national response to rabies remains reactive, fragmented, and insufficient.

There is no coordinated national rabies control programme.

Surveillance is patchy at best, and funding is often reallocated to more politically visible health issues.

In this environment, rabies thrives, shielded by a wall of bureaucratic inertia and public indifference.

Meanwhile, neighbouring countries like India have made significant strides in reducing rabies deaths through sustained public health campaigns, mass dog vaccinations, community education, and improvements in healthcare access.

Their successes starkly contrast with Pakistan’s stagnation and offer a blueprint that remains largely unheeded.

The implications of Pakistan’s failure to address rabies go beyond public health.

They speak to the broader challenges facing the country: the inability to provide basic healthcare to all citizens, the deep divide between urban and rural realities, the failure to invest in preventive healthcare, and a political culture that often values spectacle over substance.

Rabies is, after all, a disease that affects the poor far more than the rich — and in a society where economic disparities are deep and widening, it is easy for such tragedies to be overlooked.

In 2025, as the world continues to make headlines about breakthroughs in cancer treatment, the fight against pandemics, and advances in artificial intelligence in medicine, Pakistan’s battle with rabies stands as a heartbreaking reminder of the work that remains undone.

It is a preventable scourge that continues to claim lives in horrific ways, often outside the media spotlight, with little outrage and even less action.

It is a crisis that demands not just a medical response, but a moral one. Rabies in Pakistan is not merely a health issue; it is a test of the country’s commitment to its most vulnerable citizens — a test that, so far, it is failing.