The Taliban recently announced that they are suspending its polio vaccination campaign in Afghanistan. The announcement was made shortly before the campaign was due to start.

The suspension is temporary, according to the Taliban, and is due to security fears and the fact that women are involved in administering the vaccine.

Poliovirus is a highly infectious virus that mainly affects children under the age of five, but anyone who is unvaccinated can be infected. The virus spreads from person to person mainly through traces of contaminated faeces on people’s hands getting into their mouths or, less commonly, through contaminated food or water.

It initially infects the intestines, leading to symptoms such as fever, fatigue, headache and vomiting in the early stages of the disease. But, as the infection progresses, the virus can invade the nervous system, often leading to paralysis. In the worst cases, affected children will die as the paralysis spreads to the muscles that control breathing.

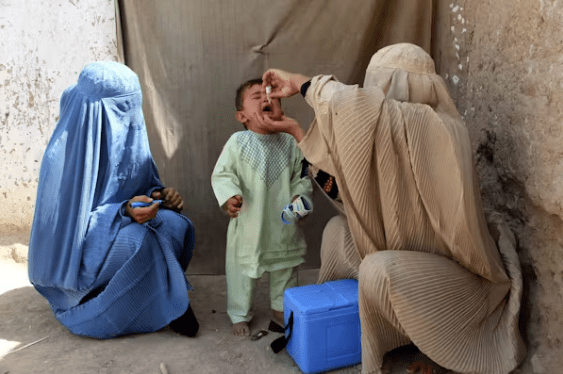

Polio was a major global childhood health concern in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, the development of polio vaccines has given us the ability to prevent polio-induced paralysis. There are two main types of polio vaccine: live-attenuated oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), made from weakened poliovirus, and inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV).

Following the introduction of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988, OPV and IPV have nearly eliminated the disease. Yet polio remains a global threat, as was seen recently with the emergence of polio in the Gaza Strip.

Afghanistan is one of only two countries, alongside neighbouring Pakistan, where polio has continued to spread. So the news that the Taliban have suspended polio vaccination will probably have major consequences for the control of the disease in Afghanistan and the surrounding region.

Earlier in 2024, Afghanistan had used a house-to-house vaccination strategy, recommended by the WHO, for the first time in five years. This tactic ensures that most children have access to the vaccine. However, in the southern Kandahar province, the Taliban used a mosque-to-mosque vaccination campaign, which has been proven to be less effective. So Kandahar is believed to have a large number of unvaccinated children who are now susceptible to infection.

Locally, this setback in vaccination not only poses a risk to the children of Afghanistan, but also poses a risk to children in bordering Pakistan. This is due to the high levels of movement across the borders between the two countries.

“Afghanistan is the only neighbour from where Afghan people in large numbers come to Pakistan and then go back,” Anwarul Haq, the coordinator at the National Emergency Operation Centre for Polio Eradication, told Associated Press.

Much wider spread

Afghanistan has already seen an increase in paralytic polio cases in 2024, rising from six in 2023 to 14 confirmed cases in 2024 so far. Paralysis occurs in about one in 200 infections, so this increase in paralytic polio suggests a much wider spread of infection in the region. This includes Pakistan, which has reported 13 cases so far this year.

With the reduced number of vaccinations and an increasing number of children vulnerable to polio infection, we are likely to see an increased number of paralytic polio cases in the near future. This potential increase in viral spread coupled with the number of people travelling in and out of the region may lead to the spread of polio beyond Afghanistan and Pakistan and into areas such as India and Iran.

Unfortunately, those who are not vaccinated will also be susceptible to vaccine-derived poliovirus. This is where the OPV vaccine, which contains a weakened version of the virus, has been able to spread in areas with low vaccination coverage, allowing the virus to return to virulence.

This has seen new vaccine-derived outbreaks seeded across several countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, which now accounts for most paralytic polio cases worldwide.