Scroll through the Google results for “artificial intelligence” and “peace”, and you’ll find some very contradictory suggestions. “Doomers” warn that AI has the potential to end life on earth as we know it. Meanwhile techno-optimist “boomers” claim AI could help to solve everything from loneliness to climate change to civil wars.

Polarised views on AI are nothing new, but interest in it as a tool for creating “peace” has risen since 2022, when OpenAI, one of the leading companies in the sector, launched its chatbot ChatGPT. A growing number of tech companies now say they’ve developed AI technologies that will help end wars.

But what are these tools? How do they work? And what are the risks when they are applied to deadly conflict?

What kind of AI are being used in peace processes?

“Artificial intelligence” refers to an array of technologies that solve problems, make decisions, and “learn” in ways that would usually require human intelligence. Some, however, argue AI is “neither artificial nor intelligent,” because it requires vast amounts of human labour and natural resources.

Still, “AI” is the term used to describe many tools that “PeaceTech” companies are developing to address violent conflict. Dedicated AI funds have been established, and the UN is actively promoting AI as a tool to support innovation.

How are AI tools being used to resolve conflicts?

Some AI tools have been built to respond to specific challenges faced by peace negotiators, such as how to gather information about public perspectives. Others serve several purposes, including recommending policies and making predictions about how people could behave.

Improving information access

In Libya and Yemen, the UN has used NLP tools to help more people share their views on politics. LLMs were used to analyse data collected when people were asked to share opinions and pose questions online. The aim was to identify agreement and disagreement across diverse groups and make peace processes more transparent and “inclusive” – which experts believe helps prevent wars.

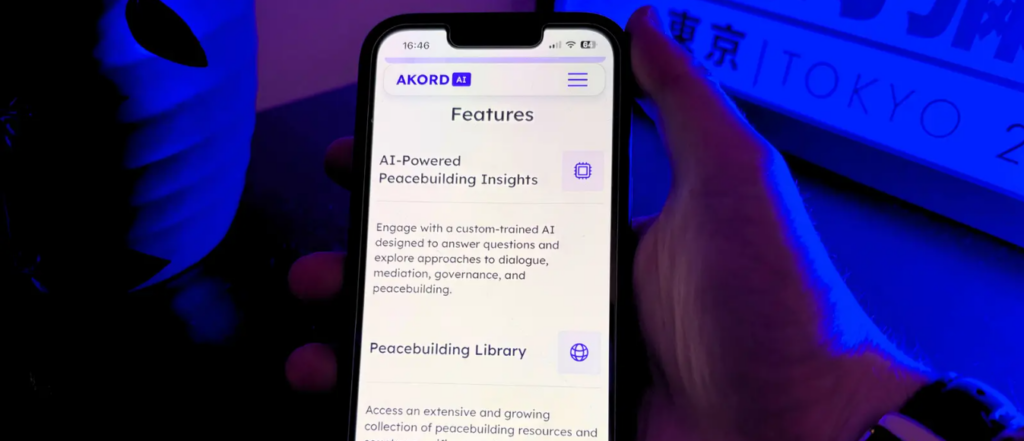

Another example is a tool called Akord.ai, developed by an NGO called Conflict Dynamics International (CDI). This LLM chatbot was trained on 1,500 documents about Sudan, which is in the grip of another brutal civil war, with a particular focus on past peace agreements.

Azza M Ahmed, a senior advisor on CDI’s Sudan Program, explained that the tool is designed to help young people who want to contribute to Sudan’s peacebuilding, but who don’t know about past processes or can’t access practical guidance on negotiations.

“In negotiations there is concentration of knowledge and expertise in the hands of the few,” said Tarig Hilal, AI innovation lead at Akord.ai. “So Akord.ai is like an advisor, a co-pilot, a friend.”

Negotiators said tools like these, built to address specific barriers to involvement in peacebuilding can be useful.

Prescriptive technologies

Some tools predict and prescribe solutions for conflicts. These tools, experts argue, should be more carefully scrutinised because the information they generate will reflect biases baked into their training data and algorithms.

Akord.ai’s chatbot also claims to help peacemakers “develop political processes and governance options”. The platform itself looks quite a bit like ChatGPT – a box to type a question or request and then the LLM’s response – although unlike OpenAI, Akord has made its training data public.

Its recommendations clearly reflect the worldview of its creator. CDI promotes a method of resolving conflict called “political accommodation”, based on power sharing and compromise. It has its supporters, but also critics. Some argue that accommodating actors with no genuine interest in sharing power has driven Sudan’s present conflict, which has killed untold numbers of civilians and displaced 11 million people.

“Groups fighting their way to the table to be ‘accommodated’ … is part of what led to the conflict,” said Jonas Horner, a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations who has worked on past Sudanese peace negotiations.

What’s more, a chatbot that learns from past peace agreements tends to recommend failed approaches, and provides only very shallow responses to questions about what stopped them succeeding. “This is not a technical set of issues,” Horner added. “This is anthropological, social … pure power calculations.”

Akord.ai is aware of these risks and told TBIJ it wants to expand its training data and get feedback from Sudanese users. Hilal emphasised that Akord.ai is not meant to replace politics. “It’s a fantastic tool, but it’s just a tool,” he said. “It’s not meant to be something you depend upon entirely.”

For now, Akord.ai is just being used to help reduce barriers to information. But if chatbots are used to help design peace agreements, poor or biased data could have serious consequences. “LLMs spit out patterns of text that we’ve trained them on, but they also make stuff up,” said Timnit Gebru, founder and executive director of the Distributed AI Research Institute

Using information from past agreements to inform future ones may also limit creative problem-solving, leading peacebuilders to design solutions that work well on paper, but fail politically.

Gebru notes that people tend to trust automated tools – a phenomenon called “automation bias”. “Studies show people trust these systems too much and will make very consequential decisions based on them,” she said.

LLMs are also being used to inform the timing of peace deals. Project Didi, an Israel-based startup, is developing tools to identify “moments of ripeness” – periods where deals may seem more acceptable, even if terms do not substantially change.

Project Didi began as an LLM trained on the language used in the years that led up to the Good Friday Agreement, which ended most of the active fighting in Northern Ireland. Project Didi’s CEO and founder Shawn Guttman said the model showed the timing of an agreement can matter more than its content.‘Studies show people trust these systems too much’

Guttman and his colleagues are adapting the model for Israel’s war on Gaza. Didi scrapes data from Israeli and Palestinian news sources and applies machine learning that claims to detect shifts in popular sentiment about peace.

According to the theory underpinning Didi’s model, confidence in winning has to drop on both sides, and people have to see a way out of the fighting at similar times. But the Palestinian model is not yet being used. LLMs are better in Hebrew than Arabic, Guttman said, and Didi has not been able to gather as much data from Palestinian media.

“There is less of a robust media presence there,” Guttman said. Israel’s war on Gaza has killed more Palestinian journalists and media workers than any modern conflict, according to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists.