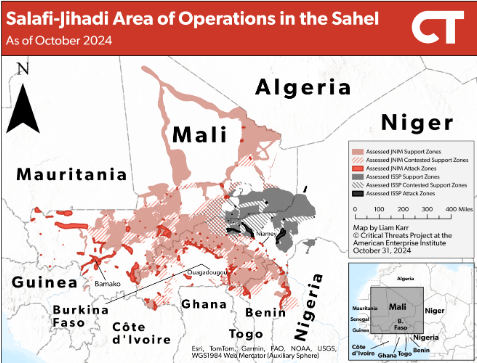

Al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates are expanding rapidly in West Africa’s Sahel region, taking advantage of long-running grievances and state incapacity. The predominant groups are Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), which is an affiliate of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISSP), previously known as Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. Salafi-jihadi activity first spiked in the Sahel when AQIM and local partners co-opted a rebellion in northern Mali and attempted to establish an emirate.[1] A French-led intervention rolled back this initial takeover, but Salafi-jihadi groups have continued to proliferate and expand in the past decade, particularly throughout central Mali and Burkina Faso.[2] JNIM and ISGS have also begun to operate in the border regions of the Gulf of Guinea states in recent years.[3]

An area where multiple groups conduct offensive and defensive maneuvers. A group may be able to conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces but has inconsistent access to local populations and key terrain.

Support Zone: An area where a group is not subject to significant enemy action and can conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces.

Methodology Note: The Critical Threats Project adapts its mapping definitions for insurgencies from US military doctrine, including US Army FM 7-100.1 Opposing Force Operations.[4] Our maps are assessments and reflect analysts’ judgment based on current and historical open-source information on security incidents, political and governance activity, and population and geographic factors. Please contact us for more information on specific maps.

Table of Contents

- November 2024 Update

- Background

- Regional Campaign Updates

- Western Mali

- Southern Mali

November 2024 Update

The latest update reflects extensive changes based on the strengthening of the regional al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates—Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) and IS Sahel Province (ISSP), respectively. There has been significant political upheaval in the central Sahel since the last update, in 2022. Burkina Faso and Niger experienced coups that installed junta governments, joining Mali’s junta, which took power in 2021.[5] The new juntas cut ties with Western partners, leading to the withdrawal of thousands of French, UN, and US troops, whom a fraction of Russian soldiers have attempted to replace.[6] The juntas have also adopted highly militarized counterinsurgency strategies that have failed to address underlying issues with the Western-backed approach of the last decade while simultaneously spreading indiscriminate violence and abuses that further fuel the insurgencies.[7] These capacity and strategy blunders have contributed to the rapid growth of JNIM and ISSP capabilities, reach, and control.[8] JNIM carried out its first attack in the Malian capital in nearly a decade and attacked the suburbs of the Nigerien capital.[9] Meanwhile, ISSP’s growth has elevated the group’s role as a regional hub and increases the risk of the branch eventually supporting global IS activity, including financially or logistically facilitating attacks in Europe.

Western partners have shifted their focus to insulating coastal West Africa against spillover from the Sahel.[11] The continued strengthening of Salafi-jihadi insurgents in the Sahel threatens to overwhelm this containment strategy. Furthermore, the political challenges with the authoritarian and anti-Western central Sahel juntas create challenges for the coastal countries and their Western partners by limiting coordination with these countries at the epicenter of the conflict

Background: The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Sahel

The Salafi-jihadi movement in the Sahel has roots in the Algerian Salafi-jihadi movement of the early 2000s, from which al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) emerged. AQIM gained influence in the Sahel throughout the 2000s, eventually infiltrating and co-opting a 2012 rebellion driven by long-running ethnic grievances in partnership with Ansar al Din, which is based in northern Mali.[13] A French-led response rolled back AQIM and its allies’ conquest of northern Mali in 2013.[14] Thousands of French and UN troops remained in the Sahel over the following decade in an effort to stem the resurgence of these insurgents.[15]

Four Salafi-jihadi groups merged to create JNIM in 2017: AQIM’s Sahara Emirate, Ansar al Din, the Macina Liberation Front, and al Murabitoun.[16] A fifth group, based in Burkina Faso, Ansar al Islam, is a de facto member of the group despite not formally being part of the merger.[17] The group maintains a top-down hierarchy that orients its strategy and coordinates between the different subgroups.[18] However, it also gives the subgroups significant operational freedom to best exploit their local contexts—such as appealing to local ethnic constituencies.[19] JNIM has embedded itself in local governance structures and implemented various forms of shadow governance through local agreements across the Sahel.[20] JNIM is most active in Mali and Burkina Faso, though it is present in Niger and expanding into the northern Gulf of Guinea states.

ISSP formed when a faction of an AQIM splinter group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2015.[21] The Islamic State did not recognize ISSP as a formal province until March 2022.[22] ISSP is most active in the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. ISSP and JNIM, unlike other al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates globally, did not initially fight each other.[23] However, the two groups have engaged in phases of conflict since 2020.[24] JNIM and French military pressure substantially weakened ISSP in 2020, but ISSP has significantly strengthened since the departure of French forces in 2022.[25]

JNIM and to a lesser extent ISSP are gradually expanding south, toward the coastal Gulf of Guinea states.[26] Overlapping issues—including climate change, poor governance, and communal tensions—are enabling the Salafi-jihadi movement to embed in local communities.[27]

Regional Campaign Updates

Western Mali

JNIM has increased the rate and geographic scope of its attacks in western Mali as it targets customs posts and roads connecting western Mali to Bamako. Since 2023, JNIM is on pace to average over twice as many attacks per year in the Kayes region as it conducted in 2022. The group conducted 21 attacks in 2023 and is on pace for nearly 25 attacks in 2024 after conducting only 10 attacks in 2022. JNIM has also carried out its first attacks in Kenieba cercle near the Guinean and Senegalese borders.[28]

The group has focused the majority of its attacks on border posts around the periphery of the Kayes region and roadways in eastern Kayes that connect to Bamako.[29] JNIM has conducted at least 15 attacks within 30 miles of the Malian border in the Kayes region since the beginning of 2023.[30] The group has likely taken advantage of the porous border security in West Africa to establish rear support zones that could help it expand further into the interior of the Kayes region.

JNIM activity near the border creates opportunities for self-sustainment. JNIM loots money and weapons from the customs posts and gendarmerie posts in some of these attacks. The group’s growing presence along the border puts it near smuggling lines involved in the illicit gold, drug, arms, and human trafficking networks that use routes connecting western Mali to coastal West Africa.[31] JNIM has historically used its positions along illicit routes in northern Mali and Burkina Faso to generate revenue.[32]

JNIM has also targeted roads connecting the Kayes region to Bamako, likely as part of a broader campaign to degrade Malian lines of communication around Bamako that began in early 2023.[33] The group carried out at least 15 attacks along major roadways in eastern Kayes that lead to Bamako since the beginning of 2023. The group has attacked security forces and civilians along the RN1 road, which connects Bamako to Kayes city, and RN24, which connects Bamako to the district capital, Kita, at least six times each.

Southern Mali

JNIM has consolidated support zones in northern Koulikoro region and western Segou region, which it uses to degrade Malian lines of communication, isolate bigger population centers, and expand southward toward Bamako. JNIM controls most rural areas of northern Koulikoro and along the Koulikoro and Segou regional border north of the Niger River. JNIM control in these areas is characterized by zakat taxation, school closures, voting prevention, and targeted abductions of local leaders with no government response. Malian counterterrorism activity in this area has also significantly declined since the beginning of 2023. Security forces initiated 22 engagements in 2022, compared with only six in 2023 and nine so far in 2024. Nearly half these security force engagements since the beginning of 2023 have been drone strikes, further illustrating the lack of state control on the ground in the area.[35]