Pakistan President Asif Zardari is visiting Gwadar at a time when the fifth insurgency since 1947 in Balochistan is now in its third decade. In 2009 in his previous term as President, Zardari had tried to bribe the Baloch with a package of economic and political sops called ‘Aaghaz-e-Huqooq-e-Balochistan’. While Zardari’s that attempt to assuage the Baloch sentiment failed miserably, he is once again trying to reach out to the Baloch, but as usual with empty words and insincere assurances.

During his visit he has called for political dialogue to bring prosperity, development and peace to the restive province. At the same time, he has called for enhancing the capacity of the law enforcement agencies. The incongruity of his message is clear to anyone who studies Balochistan: it is the lawlessness of the so-called ‘law enforcement’ and security agencies — the extortion, kidnapping, smuggling, narcotics and human trafficking networks they run — which makes them the greatest obstacle to peace in the province. What is more, the Punjab-dominated Pakistani state wants a dialogue not with genuine representatives of the Baloch but with those who will tow their line and remain subservient to the Punjabi establishment.

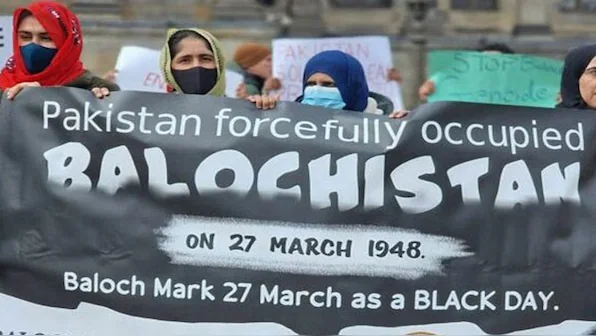

The result is that Balochistan has continued to burn ever since it was forcibly occupied by Pakistan in 1948. Since then, Pakistan has managed to keep its stranglehold over Balochistan, but only through brute force and censorship of the type that would embarrass even the Chinese.

When the first stirring of the latest and longest episode of Baloch anger against Pakistan’s neo-colonial exploitative and extractive rule started around 2001, no one expected it to last more than a few years. But the murder in 2006 of the venerable Bugti chieftain, Nawab Akbar Bugti , gave a major fillip to the Baloch movement. Since then the movement has ebbed and flowed but has continued to roll forward.