The Taliban’s abusive educational policies in Afghanistan are harming boys as well as girls and women, with the departure of qualified teachers and regressive curriculum changes.

These changes have led to increased fears about attending school, falling attendance, and a loss of hope for the future; with this, the Taliban risk creating a lost generation.

Concerned governments and UN agencies should urge the Taliban to end their discriminatory ban on girls’ education and to stop violating boys’ rights to quality education.

(London) – The Taliban’s abusive educational policies in Afghanistan are harming boys as well as girls and women, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 19-page report, “‘Schools are Failing Boys Too’: The Taliban’s Impact on Boys’ Education in Afghanistan,” documents Taliban policies and practices since they took over the country in August 2021 that are jeopardizing education for Afghan boys. This includes the dismissal of female teachers, increased use of corporal punishment, and regressive changes to the curriculum. While the Taliban’s bans on secondary and higher education for girls and women have grabbed global headlines, the serious harm done to the education system for boys has gained less notice.

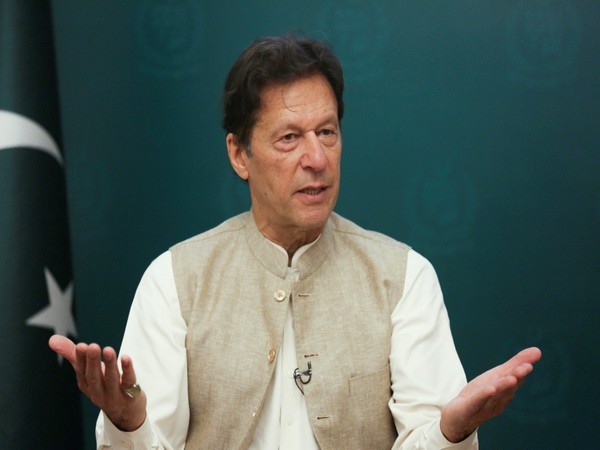

“The Taliban are causing irreversible damage to the Afghan education system for boys as well as girls,” said Sahar Fetrat, assistant women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. “By harming the whole school system in the country, they risk creating a lost generation deprived of a quality education.”

Human Rights Watch remotely interviewed 22 boys in grades 8 to 12, as well as 5 parents of boys in the same grade range in Kabul, Balkh, Herat, Farah, Parwan, Bamiyan, Nangarhar, and Daikundi provinces between June and August 2022 and March and April 2023.

The Taliban have dismissed all female teachers from boys’ schools, leaving many boys to be taught by unqualified teachers or even to sit in classrooms with no teachers at all. Boys and parents described a disturbing spike in the use of corporal punishment, including officials beating boys before the whole school for haircut or clothing infractions or for having a mobile phone. The Taliban have eliminated subjects including arts, sports, English, and civic education, causing a decline in educational quality.

“Out of 14 subjects, we [now] only have teachers for 7 subjects, and 7 subjects are not taught, … includ[ing] physics, biology, skills, computer, English, and art,” a grade 12 student at a large public high school said. “These subjects are not even removed by the Taliban. They aren’t taught because our female teachers were dismissed. Therefore, I have to take private classes outside of school,” which his family struggles to afford.

These changes have led to increased fears among boys about attending school, as well as falling attendance and a loss of hope for the future. The country’s deepening humanitarian and economic crises have placed greater demands on boys to work to support their families, forcing many to leave school altogether. Boys are increasingly struggling with anxiety, depression, and other mental health problems in a context in which mental health services are sparse.

While the Taliban have not prohibited boys’ education beyond sixth grade, as they have for girls and women, their actions undermine access to education for all children and young adults. This violates Afghanistan’s obligations under international law, including the right of all children to education. The Taliban’s systematic discrimination against women and girls—of which the ban on girls and women studying is only one aspect—is also having harmful effects on boys, including by teaching them harmful gender norms and putting greater pressure on them be the sole financial providers for their families.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, which Afghanistan ratified in 2003, governments are obligated to ensure “the elimination of any stereotyped concept of the roles of men and women at all levels and in all forms of education.”

Corporal punishment of children in schools is a violation of their human rights, Human Rights Watch said. The use of violence to punish children causes unnecessary pain and suffering, is degrading, and harms children’s development, educational success, and mental health. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has found that all corporal punishment is prohibited under international law and all children have the right to an education in an environment free from violence. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Afghanistan ratified in 1994, lays out children’s rights to education, safety, and protection from violence.

Concerned governments and UN agencies should urge the Taliban to end their discriminatory ban on girls’ and women’s education and to stop violating boys’ rights to safe and quality education, including by rehiring all women teachers, reforming the curriculum in line with international human rights standards, and ending all corporal punishment.

“The Taliban’s impact on the education system is harming children today and will haunt Afghanistan’s future,” Fetrat said. “An immediate and effective international response is desperately needed to address Afghanistan’s education crisis.”

Dismissal of female teachers

“For grades 10, 11, and 12, we had a total of 16 female teachers and 4 male teachers,” said Wahid M., a student in grade 12 in Kabul. “Our female teachers had specializations in the subjects they taught: they were professionals. We are suffering from their absence now and our four male teachers also fled the country after August 2021. Currently, we are taught by male teachers who previously taught grades four and five.”

Nateq A., a grade 12 student at a large public school in Kabul, said: “Ninety percent of teachers teaching grades 10, 11, and 12 at my school were female. After the Taliban came to power, they were replaced with male teachers. For my class, four new teachers have been assigned. They spend more time talking about religion, the Prophet Muhammad’s way of life, and the Taliban’s victory of jihad against the US and the West, than teaching their assigned subjects.”

Corporal punishment

Abdul R. said: “I have been beaten and badly humiliated during the morning assembly in front of everyone, once for having a mobile phone with me and the second time for my hairstyle. They cut my hair in front of everyone during the morning assembly, saying it resembled ‘Western style,’ and after that, I was punished with foot whipping.”

Zaman A., a student in Herat, said: “The Taliban’s strict rules are suffocating. Currently, as a student, wearing anything colorful is treated like a sin. Wearing shorts, t-shirts, ties, and suits are all treated like crimes. Having a smartphone at school can have serious consequences. Listening to music or having music on one’s phone can lead to severe physical punishment. Every day, there are several cases where boys get punished during morning assembly or in classrooms for some of these reasons.”

Muhammad R. said: “School is not fun like it used to be before. The constant fear of a sudden visit from the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice has made it even more stressful. Some boys escape school and smoke cigarettes and hashish or drink alcohol. They then get caught by the Taliban soldiers and brought back to school and get beaten.”

Zahir Q. said: “There is more focus on learning the Pashto language at our school. One new teacher asked my classmate to write a poem in Pashto, but my classmate was unable to do it. The teacher made him stand on one foot in front of the classroom, slapped him in face several times, and pulled his ears. My classmate felt humiliated.” He added: “Teachers didn’t have the right to humiliate or beat students in the past. In some cases where this would happen, students had the right to complain.”

Harmful changes to the curriculum

A 78-page document titled “Report of the Modern Curriculum Assessment Committee,” which Human Rights Watch obtained in January 2022, appears to be an internal Taliban proposal for revising the curriculum. While it was not possible to confirm the authenticity of the document and whether its proposals would ultimately be implemented, the changes it suggests are similar to those reported by students and other sources. The document states that:

“The current curriculum has been developed under the supervision of the Kabul puppet government’s Education Directorate and its publication was funded by Jewish and non-religious countries. Therefore, it is highly likely that it adheres to un-Islamic and non-Afghan standards that resemble Western standards. However, these superstitions have been cleverly woven into it in such a skillful way that it appears Islamic on the surface, but from a linguistic perspective, the imagery and description reveal ugly intentions that require the skill and analysis of a master [to detect].”

Zahir Y., a student in Farah province in the southwest, said: “I don’t understand the difference between my school and our local mosque anymore. We are lacking professional teachers who taught us important subjects such as physics, computer science, and chemistry.”

Low Attendance: Impact of Economic Crises and Low Quality of Education

Sadiq T., a student in grade 11 in Kabul, said many of his classmates no longer came to school and that he had lost his motivation to study. “I have no interest in finishing high school,” he said. “A person who has no knowledge and expertise is brought to teach us physics and chemistry. This is a crucial year for us, and we cannot prepare for university entrance exams with such illiterate teachers.”

Abdul G., 13, in Daikundi province, said: “Since the fall of the republic government [in 2021], our schools are falling, too. At my school, you can only find three or four boys present at the secondary level.” He added: “The boys are not coming to school because they need to work. No one feels motivated. Public schools are free, but food is not, buses are not, notebooks, textbooks, and our clothing are not free.”

“Most boys are panicking about jobs and survival,” said Abdul S., 15, in grade 10 in Bamiyan. “In my school, most boys in grades 10, 11, and 12 have either dropped out of school for work inside the country or crossed the border illegally to Iran or Pakistan for work. If it continues like this, our school will be shut down too.” He said that “in the past, we would usually have 38 out of 42 students present in my class. Since the fall of the government, there are typically only 12 to 15 students present. There must be multiple reasons for such low attendance, but the Ministry of Education doesn’t care.”