The Gwadar seaport was supposed to develop the local economy, connect Pakistan to the world, and give China access to the Indian Ocean. So why aren’t locals happy with it?

Funded and operated by China, Pakistan’s port at Gwadar has been touted as a competitor to regional ports like Dubai in the UAE and Chabahar Port in Iran. But what started off as a small fishing town has now transformed into a securitized and segregated harbor settlement, whose economic benefits are not enjoyed by the local population.

Back in 2015, Chinese President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 and Pakistan’s then prime minister Nawaz Sharif unveiled plans to expand the development of a deep-water port at the small town of Gwadar. The project is a key part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which was originally proposed to involve $87 billion of investment from Beijing, and is a major part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

It’s not Shenzhen, despite the hype

Gwadar Port was declared “fully operational” in 2021, but it’s unclear how much cargo it is currently handling. You can find various facts about the port on its website; Chinese state media modestly said in July this year that “at present, the terminal can accommodate two 50,000-ton cargo ships at the same time.” In 2021, a reporter from the nonprofit website Third Pole, which covers water and environmental issues in the Himalayan watershed area, said that the only activity at the port was by a couple of crabs climbing on the dock, while the “towering blue and red cranes, brought there to load and unload shipping containers, were still.”

The Chinese government has hyped the port development as being “inspired by…Shenzhen,” and Pakistani officials have echoed that phrasing. And indeed, although Gwadar was once a remote fishing village — like Shenzhen was until the early 1980s — it now boasts a coal-fired power plant and a vocational training institute, with a hospital and an airport slated to open within the next few months, all funded by China. Both Pakistani and Chinese governments tout the development’s huge potential to lead regional economic growth.

But “the vision to build a world-class port is well described but makes little sense in isolation from broader economic development in the hinterland of the port,” Peter Borup, former CEO of Norvic Shipping International, told The China Project.

“The port is currently only deep enough for very standard imports of coal, fertilizers, and grains,” he added. And while the next phase in the planned development of Gwadar Port is to dredge to achieve a draft of approximately 20 meters (65 feet), enough for the largest container ships, compared with its current depth of about 14 meters (46 feet), Borup said that “Pakistan’s economy is nowhere near to having an economy that warrants such big ships.”

Gwadar Port offers Beijing the chance to build an energy and transport corridor straight to China from the Indian Ocean and the oil- and gas-rich region of the Strait of Hormuz. Gwadar is the closest possible port location to Iran and Saudi Arabia on Pakistan territory. It looks like an ideal place for Beijing to extend a Belt and Road spoke directly from China to the Indian Ocean.

But here’s where the problem starts: Gwadar is in the southern part of Pakistan’s province of Balochistan, which is resource rich but whose more than 12 million people have a per capita GDP of under $1,000, in the same range as Chad and Afghanistan.

A segregated port settlement

While Gwadar Port has been in development with Chinese funding for more than seven years, many locals do not see any benefits to their own lives, or improvements in basic infrastructure outside of the fenced-off port.

“This generation of youth in Gwadar grew up over the past 20 years with a dream that Chinese money would transform Gwadar into a new Dubai or Singapore, but what they see today is enough to shatter their hope,” 50-year-old Nasir Rahim Suhrabi, a social activist in Gwadar, told The China Project.

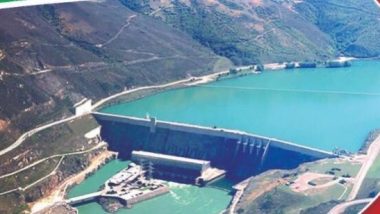

A view of Gwadar Port, November 2022. Out of view at the left are fences that keep the port sealed off from the town. Click here to zoom out from the above photo and see the areas surrounding the port. Photo for The China Project by ANON.

“The whole city has been converted into a security zone. Locals face restrictions and security checks to move across the port city. The mini fish harbor has become a part of Gwadar Port, where local fishermen no longer enjoy free access to the harbor, since they have to pass through security protocols,” he added.

Koh-i-Batil, a hilly area just south of Gwadar Port, used to draw crowds for its sea views. “It used to be a place for entertainment for local visitors before construction began. Now they cannot enter the area without passing through various security checkpoints,” Suhrabi said.

Political activists also claim that the way that the port city is being developed puts locals at a disadvantage.

“I would say the problems have worsened with the development of Gwadar Port over the past two decades,” Kalsoom Baloch, another activist in Gwadar, told The China Project. Baloch previously participated in protests demanding rights for local residents in Gwadar.

“The locals are anxious,” she said, and explained:

Many of them depend on fishing to earn their livelihoods. Now their access to the sea has become more difficult due to certain security protocols set by Pakistani authorities. Locals do not generally meet the eligibility criteria, such as higher education, vast experience, and relevant skills, required for the key jobs in the Gwadar project. They are not against development, but they want their due representation in the process.

In interviews with The China Project, other Gwadar locals have expressed fears that they will become an underrepresented minority if the port development really takes off.