When Salman Rushdie’s fourth novel, “The Satanic Verses,” appeared in its English-language first edition on September 26, 1988, the writer could not yet have imagined that this book would fundamentally change his life.

Now, nearly 34 years later, numerous festivals and literary associations have invited people to solidarity readings — not to mark this year’s anniversary, but because of the assassination attempt against Rushdie decades after Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for the author’s murder in February 1989.

“The Satanic Verses” was first published in Britain, then in the United States, Italy and France. Muslims quickly protested against the novel and its author. South Africa, India and Pakistan stopped the import of the book; people ended up dying during demonstrations.

In London, where Rushdie was living at the time, there were also violent protests, arson attacks and threats against bookstores selling the novel.

Rushdie’s story is about two Indian actors who survive a plane crash. One becomes an archangel; the other resembles the devil. The title of the novel refers to two verses that are said to have been whispered to the Prophet Muhammad by Satan and therefore erased from the Koran.

“The Satanic Verses” in German

In fact, Rushdie’s novel is not a critique of Islam, but a narrative about postcolonialism and migration. Rushdie later said that he never wanted to insult Islam. He could have done that in five minutes instead of working on a book for five years, he said.

Almost half a year after the novel’s publication, Khomeini issued a fatwa, or Islamic legal opinion, calling on all Muslims to kill the British-Indian writer for alleged blasphemy. Rushdie immediately went into hiding, living in secrecy and under personal protection for nine years.

‘Fatwa led to paralysis’ for German publisher

Khomeini directed the death call not only against Rushdie, but against everyone involved in the publication of the novel.

A quarter of a year earlier, Reinhold Neven DuMont, then head of publishing at Kiepenheuer & Witsch, had acquired the book rights for the German-language market. He later describes it as his biggest mistake not to have read the complete manuscript in advance — not because of the impending danger itself, but because he had thus not seen it coming.

“The fatwa led to paralysis in the publishing house,” Helge Malchow, editor at the time and later publishing director, told DW. Some of the staff wanted to drop publication, if with a heavy heart, because of the life-threatening situation. “Others wanted to defend artistic freedom and publish the book,” he recalled.

The translator who had already been commissioned halted the project, and Kiepenheuer & Witsch refrained from the planned publication for the time being.

Public criticism of the dithering attitude was gathering steam, but Malchow cautioned that “it was the first Islamist threat of this kind, and it caught us completely unawares.”

Published in taz newspaper

Arno Widmann, co-founder of Germany’s left-wing taz daily, told DW that he saw things differently.

“I thought it was a crime not to publish the book,” he said.

German writer Hans Magnus Enzensberger turned to Widmann’s friend Frank Berberich, publisher of the culture magazine Lettre International. Enzensberger suggested Berberich print excerpts from Rushdie’s book there.

But the idea was dropped because of the magazine’s quarterly publication cycle. Berberich suggested printing excerpts in taz.

“I thought it was a crime not to publish the book,” Arno Widmann said

Widmann severely criticized the German publishing industry in several articles at the time. He said Germany was hiding while other countries were standing up for freedom of expression, and that these publishers were not intimidated by the protests.

So, when taz went ahead and printed the excerpts, as expected “we received too little attention,” Widmann said.

Assassinations and brutal attacks

Despite the clamorous criticism of the publishing decision, the concerns turned out to be well-founded. In July 1991, the Italian translator Ettore Capriolo survived a knife attack in Milan with serious injuries. A few days later, Hitoshi Igarashi, a Japanese translator and Islamic scholar, was stabbed to death by one or more unknown persons in front of his office at the University of Tsukuba.

Jamshid Khasani, who had translated “The Satanic Verses” into Farsi, fled Tehran in 1992 via several countries to Israel, where he settled under a new name.

After the Turkish writer Aziz Nesin announced that he would publish excerpts from Rushdie’s book, Islamists carried out an arson attack on a culture festival in 1993 because Nesin was scheduled to be there. Nesin managed to escape, but 37 people died. That same year in Oslo the book’s Norwegian publisher, William Nygaard, was shot three times, an attack he survived.

Decades later, on August 12, 2022, Rushdie himself survived an assassination attempt, though was seriously injured. He was on artificial respiration for a time and will suffer permanent damage.

After years in hiding and under police protection, Rushdie has described living in New York freely and without concern for his life.

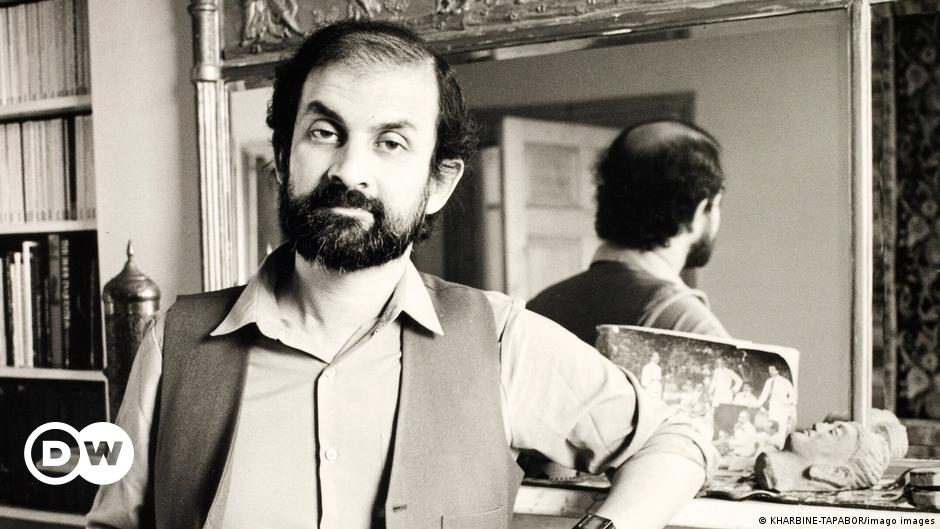

Salman Rushdie – A marked man

Publishing house for just one book

Back in 1989, about 100 publishing houses, writers’ associations, editors and authors got together to found a new publishing house that would publish “The Satanic Verses” in German. The idea was that no publishing house should be the sole target of possible retaliatory attacks. Kiepenheuer & Witsch was responsible for printing and distribution.

The Article 19 publishing house, whose name refers to the freedom of expression in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, served the sole purpose of publishing Rushdie’s novel. The collective donated the profits of the sales to the PEN writers’ association for the benefit of persecuted authors.

Rushdie was not happy about the collective solution; he would have preferred his publisher to take an unequivocal stance. “He was downright outraged,” Helge Malchow remembered, adding the writer felt the decision was like backing off from the threat.

On October 17, 1989, “The Satanic Verses” hit the German-language market. To this day, the person who translated the novel has not been publicly identified.

Bernhard Robben, translator

‘Concentrated hatred’

Bernhard Robben, who later translated several of Rushdie’s works into German, told DW that, as much as he would have liked to translate the book, he struggled with the idea of living “in fear of death.”

The translator had met Rushdie earlier through a mutual friend, the British writer Ian McEwan. Robben was living in Oxford at the time and he and Rushdie met and got along well. But then Rushdie had to go into hiding.

After the fatwa was announced, Robben finally agreed to translate “The Satanic Verses.” He recalls friends were aghast. He told them “I can’t not do it.”

It was unthinkable to him that this book would not be published in German and that the attack on freedom of expression would succeed.

In the end, the publishing collective decided to have several translators work simultaneously so that publication would not be delayed.

In his 2012 memoir, “Joseph Anton” — his alias under police protection — Rushdie speculates that “The Satanic Verses” would not find a publisher today because the risk of attacks is greater today than back then.

Bernhard Robben, who co-translated “Joseph Anton,” is in fact “pretty sure it wouldn’t be published today.”

PEN: No freedom for the word Salman Rushdie The British-Indian author quickly earned the ire of Iran’s Ayatollah after publishing his book “Satanic Verses” in 1988. The book makes several references to figures in Christianity and Islam, leading Ayatollah Khomeini to issue a fatwa against the writer and calling on Muslims all over the world to kill him. The book’s Japanese translator was assasinated in 1991.

PEN: No freedom for the word Maria Ressa Maria Ressa is co-founder and editor-in-chief of the Rappler online news portal in the Philippines. Previously, she worked as a reporter for CNN. In the Philippines, the Nobel Peace Prize winner was the harshest critic of former President Rodrigo Duterte and his brutal anti-drug policy.

PEN: No freedom for the word Selahattin Demirtas Turkish opposition politician Selahattin Demirtas ran against President Erdogan in the 2014 and 2018 elections. He has been held in a high-security prison since November 2016 for alleged terrorist propaganda. The European Court of Human Rights is demanding his release. Turkey, a member of the Council of Europe, is not responding. While in prison, Demirtas began writing.

PEN: No freedom for the word Rahile Dawut Like hundreds of Uighur intellectuals, Rahile Dawut disappeared from public view without a trace in 2017. According to Human Rights Watch, the well-known ethnologist from Xinjiang was arrested during a crackdown on Uighur poets, academics, and journalists. She is presumably being held in an internment camp. The German PEN Center is campaigning for Rahile Dawut.

PEN: No freedom for the word Kakwenza Rukirabashaija Rukirabashaija’s case sheds light on the situation of freedom of expression in Uganda. The regime critic, author and lawyer was abducted and tortured in 2021 because of critical books and disrespectful tweets. With the help of PEN, he managed to escape to Germany, where he arrived in February 2022.

PEN: No freedom for the word Pham Doan Trang Politically motivated charges and arrests — the government has targeted Vietnamese blogger and journalist Pham Doan Trang for her campaigning against environmental destruction, police violence and the oppression of minorities. Many human rights organizations and governments have been demanding her release after she was sentenced to nine years in prison in 2021.

PEN: No freedom for the word Osman Kavala When Turkish culture promoter Osman Kavala disappeared behind bars on flimsy charges in April 2022, it was not only PEN that protested. Amnesty International has also been calling for Kavala’s release. The Council of Europe has repeatedly criticized Turkey’s failure to comply with the European Convention on Human Rights.

PEN: No freedom for the word Tsitsi Dangarembga Tsitsi Dangarembga, author and filmmaker, is once again on trial in her native Zimbabwe for anti-government protests. She is accused of inciting public violence, breach of peace and bigotry. Dangarembga received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 2021. If found guilty, she faces several years in prison. Author: Stefan Dege

This article was originally written in German.