Sign up to our free IndyArts newsletter for all the latest entertainment news and reviews Sign up to our free IndyArts newsletter Please enter a valid email address Please enter a valid email address SIGN UP I would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our privacy notice Thanks for signing up to the

IndyArts email {{ #verifyErrors }}{{ message }}{{ /verifyErrors }}{{ ^verifyErrors }}Something went wrong. Please try again later{{ /verifyErrors }}

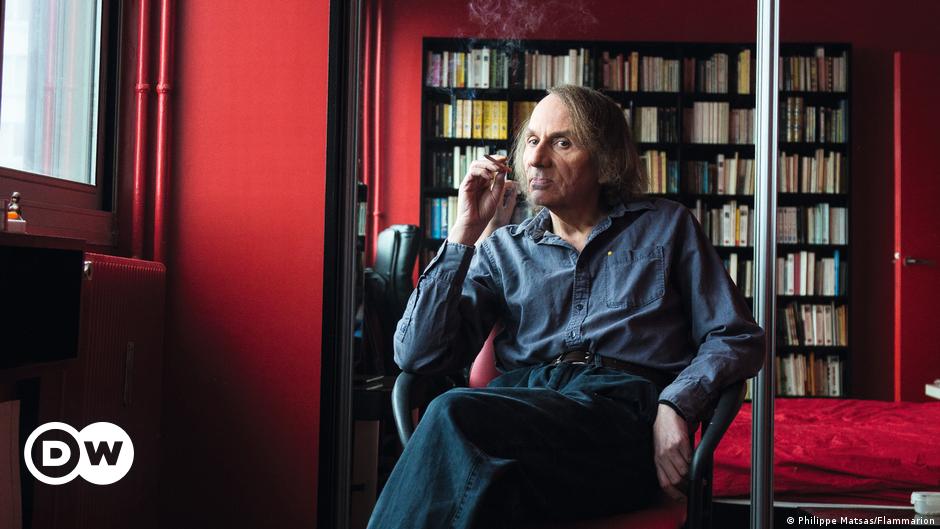

Kamila Shamsie can still remember with absolute clarity a moment that happened to her many years ago when she was a teenage girl in Karachi. “I was in a car with a bunch of friends and a man was driving. We were having fun and then, in an instant, something shifted and it became dangerous and threatening. Fortunately, the moment passed quickly but I’ve never forgotten it.” The moment, barely 30 seconds long, contained a shift in the atmosphere rather than an actual threat, but it was full of meaning nonetheless. “As you become older what becomes clearer is how early on, if you are female, that feeling of sexual risk enters your life,” says Shamsie. “You are suddenly made aware that the world is dangerous for girls.”

That car ride features in slightly different form in Shamsie’s new novel, Best of Friends, both an adolescent coming-of-age novel and paean to female friendship. The first half is set in Karachi in 1988 and draws intimately on an emotional level on Shamsie’s remembered adolescence. Close as thieves since the age of four, Zahra and Maryam share a binding love for George Michael and Jackie Collins despite their different backgrounds – Zahra’s parents are arty and middle class; Maryam’s boast establishment connections and are far wealthier. But then comes the thing that changes everything. Zahra steps into a car containing a male school friend and an unknown man and, after a moment’s hesitation, Maryam follows her. Suddenly they are aware they are trapped in a situation they will be unable to control. Nothing too appalling happens, but afterwards Maryam is sent to boarding school in England, while Zahra will be marked by the abrupt power shift that occurs inside the car long into adulthood, unable to fully forget the inchoate feelings of shame that the moment provoked, despite not being at all responsible. “It’s a feeling many women can carry with them for the rest of their lives,” says Shamsie. “Every time I’ve mentioned that experience of mine to female friends, regardless of where they grew up, they say, ‘Oh yes, we know that car ride.’”

Best of Friends, picking up the story of Maryam and Zahra’s friendship in 2019, by which point both have established successful careers in London, is Shamsie’s first novel since she won the Women’s Prize for Fiction for her 2017 novel Home Fire – a moment she describes as one of the greatest of her life. It’s particularly excellent on the particularities of adult friendship forged in childhood. “My oldest friends know all the versions of me,” says Shamsie, with a laugh. We are speaking over Zoom earlier this summer, on the day the mercury will hit 38 degrees (Shamsie has stocked up on watermelon) but Shamsie is so engaging and warm we might as well be in the same room. “I have very different political views now to many of those friends, but you get to your forties and you realise how these people are carrying your childhood self.”

Like many of her novels, it’s also deeply interested in how personal lives are shaped by wider political forces: 1988, of course, was the year Pakistan’s military dictator General Zia is widely believed to have been assassinated in Pakistan (he died in an unexplained plane crash). It was after this that Benazir Bhutto took over, making her Pakistan’s first female democratically elected leader. That relatively short-lived moment in Pakistan’s history, imbued with democratic optimism and feminist hope, provides a richly symbolic backdrop to the first half of the novel, yet I suggest, it also now feels very far away. After all, the four-year rule of Imran Khan, who was removed from power earlier this year following a no-confidence vote, was marred by his religiously motivated clampdown on women’s rights and his support for the Afghani and Pakistani Taliban. Yet Shamsie, who became a British citizen in 2013, is wary of being too critical of her home country.

“I don’t want to come across as the expat who says, ‘This is how things are,’” she says. She was so incredulous when she first heard about Zia’s death from a school friend, she initially assumed it was joke – even so, “At 15, I believed that everything was about to change. But at this point, I no longer think that. The thing is, it’s hard to talk about Pakistan without linking it to populist governments that are in power all around the world, and the disillusionment that comes out of these successive political failures. Someone recently asked me whether things in Pakistan had got better. I said, ‘No, but things everywhere else have got worse.’ The gap has closed.”

Shamsie, 49, grew up in a secure, affluent, intellectual environment in Karachi and always knew she wanted to be a writer, publishing her first novel, In The City By The Sea, at the age of 25. Her first four books, all about her childhood home, were well received if perhaps not so widely read, but her career took off with 2009’s Burnt Shadows, which was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction. She has lived in London since 2007 (though still spends part of each year in Karachi) and is, she puts it, fully established – she has a healthy bank balance, is paid to write books, is shortlisted for prizes and often appears on Radio 4. Those things were also true back in 2012, but she still felt extremely nervous about applying for British citizenship. “I was at the privileged end of the scale… yet every time I handed in an application for visa renewal there was terror that it would not be accepted,” she says. “Later, stories started coming out around the Windrush Generation and more broadly concerning the reasons why people were being rejected. I remember reading them thinking, yes, if those stories had been out five years earlier I’d have been even more panic-stricken.”

At 15, I believed that everything was about to change. But at this point, I no longer think that Kamila Shamsie

She has long been a vocal critic of the British government’s immigration and civil rights policies and tells me she only felt able to write Home Fire – which updates Sophocles’ Antigone to offer a piercing critique of Islamophobia within the British political establishment – after she became a citizen of this country. “One of the things that became interesting to me as I was comparing 1980s Pakistan with 2019 Britain is that [under Zia] we were very aware we were living under a surveillance state. We have a different version of that here, but we do have it. I am very interested in how countries who have established democracies think they can tear up the norms. It’s really dangerous. It’s not just proroguing and attempts to overturn the Supreme Court; it’s who is paying what to political parties and what they get in return. We saw a lot of that cronyism during Covid. And I wasn’t at all surprised.”

Kamila Shamsie’s new book ‘Best of Friends’ (Bloomsbury Publishing)

Best of Friends also has a subplot featuring an asylum seeker that acutely reflects the extent to which current state policy foments public anti-immigration hostility. But Shamsie also wonders if on this issue, at least, we might have reached a turning point. “Brexit legitimised anti-migrant feeling,” she says. “But we are now at this very horrible, interesting moment where the government’s anti-migrant position is now massively outflanking that of the British public. The Rwanda plan was that moment. For all the anti-migrant sentiment, this is not what most people want to happen.” We’ll see if she’s right.

‘Best of Friends’ is published today by Bloomsbury