After waiting for almost a year, the United Nations Human Rights Office released the Xinjiang report on Wednesday, suggesting that China’s large-scale internment and treatment of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in western China may amount to “crimes against humanity.”

Human rights organizations have weighed in on the significance of this report, saying the findings expose the extent of harm that China has done to more than one million ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang region. Others say the final results show why Beijing tried so hard to prevent the report from being released.

HRW: ‘Sweeping rights abuses’

“The High Commissioner’s damning findings explain why the Chinese government fought tooth and nail to prevent the publication of the Xinjiang report, which lays bare China’s sweeping rights abuses,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. “The United Nations Human Rights Council should use the report to initiate a comprehensive investigation into the Chinese government’s crimes against humanity targeting the Uyghurs and others — and hold those responsible to account.”

Omer Kanat, the executive director of the Uyghur Human Rights Project, described the UN report as a “game changer” and Dolkun Isa, President of the World Uyghur Congress, said “it paves the way for meaningful and tangible action by member states, UN bodies, and the business community.”

UN releases report on China’s treatment of Uyghurs

But for others, the UN’s report has been a case of too little, too late.

Rayhan Asat, a Uyghur human rights lawyer and non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, told DW that the report should not only document the attention-grabbing horrors of the camp, but also the criminalization of everyday Turkic and Muslim cultural expression in the name of countering “extremism.”

“China should understand this as a demonstration of the world’s seriousness about defending and protecting Uyghur rights, and that if it wishes to be seen as a world leader, then it must immediately abandon the genocidal policies that are making it an international pariah once again,” she said.

Asat is not alone in her criticism of the way the UN has handled the case.

“If this report was released when it was ready, we might have had less casualties,” said Nury Turkel, the chair of the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, who is a Uyghur lawyer.

“The damage done to the Uyghur people is irreversible. No one can bring it back to us. This crime is still underway. I don’t have words for my disappointment and dissatisfaction with the UN,” he told DW.

On Wednesday, the Chinese ambassador to the UN, Zhang Jun, said Beijing was in complete opposition to the allegations made in the report, while adding that the documents haven’t been made available to them. This is in contrast to what the UN’s human rights chief, Michelle Bachelet, said upon the report’s release, stating it had been provided to the relevant authorities in China.

“It simply undermines the cooperation between the UN and a member state. It completely interferes in China’s internal affairs,” Zhang Jun said.

Last week, Bachelet admitted that she was facing “tremendous pressure” over the Xinjiang report. In an emailed statement to news agency AFP on Wednesday, Bachelet said the issues are serious while repeating that she had brought them up with Chinese authorities during her trip there in May.

Bachelet also insisted that dialogue with China didn’t mean “turning a blind eye.”

“The politicization of these serious human rights issues by some states did not help. They made the task more difficult, they made the engagement more difficult and they made the trust-building and the ability to really have an impact on the ground more difficult,” she said.

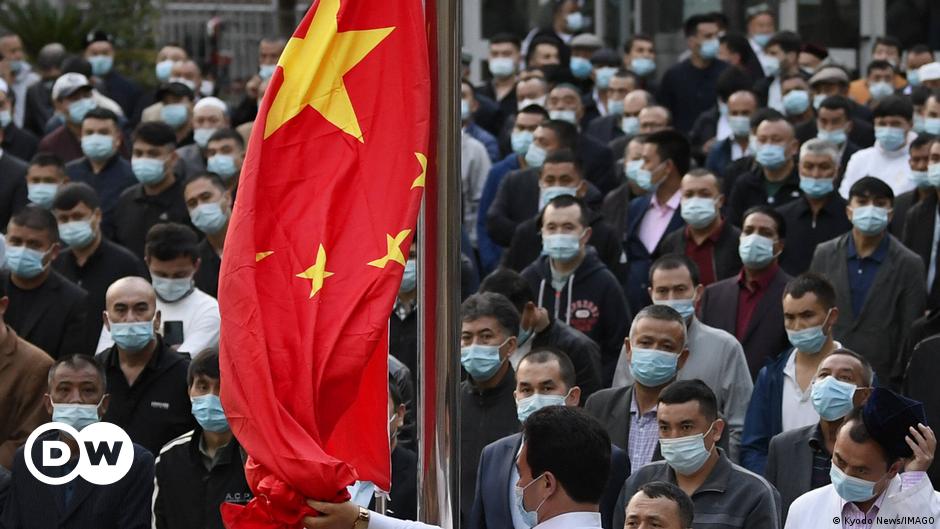

Protests have gone global to defend the rights of Uyghurs, including this one outside the Chinese embassy in London earlier this year

Activists criticize Bachelet

However, some human rights activists told DW that Bachelet has failed to fulfill the duties that come with the role of UN human rights chief.

“The post of the high commissioner for human rights requires you to be a champion of human rights beyond states. You are not a mediator between governments, which is a role that she has been assuming in this situation,” said Raphael Viana David, a China and Latin America Advocate at the International Service for Human Rights (ISHR).

“She should represent the higher interest of human rights in the world beyond geopolitical concerns. This has been one of our main criticisms of her approach to China,” he added.

But for some Uyghurs whose family members remain stranded in Xinjiang, the report helps to bring China’s persecution of Uyghurs back into the global spotlight.

“The report makes the Uyghur situation more known to the world, especially the member states of the UN,” said Mamutjan Abdurehim, an exiled Uyghur man in Australia who has been separated from his wife and two children since 2016.

“I hope this report will be a fresh rattling cry for more condemnation and pressure on China so it can reverse its policies and release those innocent people like my wife while reuniting Uyghur families like mine,” he told DW.

What happens next?

With the report now being made public, Viana David from ISHR, says the next important step is for countries in the UN human rights council to form a coordinated and multilateral response.

“As the human rights council will start its next session in a bit more than a week, the diplomatic community in the council should coordinate strong responses that include public condemnation and the reiteration of the recommendations and findings in the report,” he said.

Additionally, he thinks member states should try to create a UN mechanism that will monitor the situation in China. “This mechanism should look at the situation in China overall. The report gives an impetus for an investigation or provides key momentum to look at the human rights situation not only in Xinjiang but also in China overall,” he added.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state China’s far western Xinjiang region ramps up security Three times a day, alarms ring out through the streets of China’s ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar, and shopkeepers rush out of their stores swinging government-issued wooden clubs. In mandatory anti-terror drills conducted under police supervision, they fight off imaginary knife-wielding assailants.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state One Belt, One Road Initiative An ethnic Uighur man walks down the path leading to the tomb of Imam Asim in the Taklamakan Desert. A historic trading post, the city of Kashgar is central to China’s “One Belt, One Road Initiative”, which is President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign and economic policy involving massive infrastructure spending linking China to Asia, the Middle East and beyond.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state China fears disruption of “One Belt, One Road” summit A man herds sheep in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. China’s worst fears are that a large-scale attack would blight this year’s diplomatic setpiece, an OBOR summit attended by world leaders planned for Beijing. Since ethnic riots in the regional capital Urumqi in 2009, Xinjiang has been plagued by bouts of deadly violence.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state Ethnic minority in China A woman prays at a grave near the tomb of Imam Asim in the Taklamankan Desert. Uighurs are a Turkic-speaking distinct and mostly Sunni Muslim community and one of the 55 recognized ethnic minorities in China. Although Uighurs have traditionally practiced a moderate version of Islam, experts believe that some of them have been joining Islamic militias in the Middle East.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state Communist Party vows to continue war on terror Chinese state media say the threat remains high, so the Communist Party has vowed to continue its “war on terror” against Islamist extremism. For example, Chinese authorities have passed measures banning many typically Muslim customs. The initiative makes it illegal to “reject or refuse” state propaganda, although it was not immediately clear how the authorities would enforce this regulation.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state CCTV cameras are being installed Many residents say the anti-terror drills are just part of an oppressive security operation that has been ramped up in Kashgar and other cities in Xinjiang’s Uighur heartland in recent months. For many Uighurs it is not about security, but mass surveillance. “We have no privacy. They want to see what you’re up to,” says a shop owner in Kashgar.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state Ban on many typically Muslim customs The most visible change is likely to come from the ban on “abnormal growing of beards,” and the restriction on wearing veils. Specifically, workers in public spaces, including stations and airports, will be required to “dissuade” people with veils on their faces from entering and report them to the police.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state Security personnel keep watch Authorities offer rewards for those who report “youth with long beards or other popular religious customs that have been radicalized”, as part of a wider incentive system that rewards actionable intelligence on imminent attacks. Human rights activists have been critical of the tactics used by the government in combatting the alleged extremists, accusing it of human rights abuses.

China’s Uighur heartland turns into security state Economy or security? China routinely denies pursuing repressive policies in Xinjiang and points to the vast sums it spends on economic development in the resource-rich region. James Leibold, an expert on Chinese ethnic policy says the focus on security runs counter to Beijing’s goal of using the OBOR initiative to boost Xinjiang’s economy, because it would disrupt the flow of people and ideas. Author: Nadine Berghausen

Edited by: John Silk