Sign up to our free US news bulletin sent straight to your inbox each weekday morning Sign up to our free morning US email news bulletin Please enter a valid email address Please enter a valid email address SIGN UP I would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our privacy notice Thanks for signing up to the

US Morning Headlines email {{ #verifyErrors }}{{ message }}{{ /verifyErrors }}{{ ^verifyErrors }}Something went wrong. Please try again later{{ /verifyErrors }}

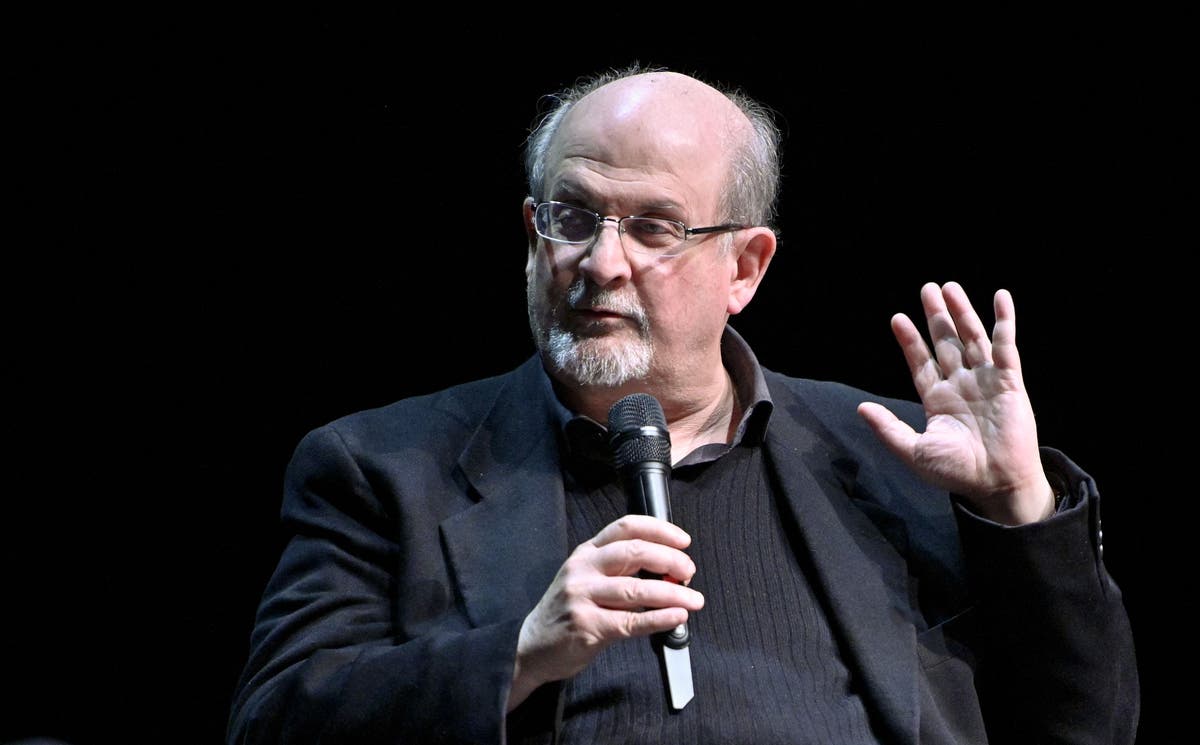

For the past several years, it seemed as if the threat had finally abandoned him. Before he was attacked, Salman Rushdie was mounting a stage in New York state to speak of how America had given him, and many writers and artists before him, a sanctuary.

Ever since he left Britain in 2000, he was able to resume the life that had been denied to him ever since that moment, on Valentine’s Day in 1989, when Ayatollah Khomeini pronounced a fatwa calling for his death. He was a fixture at literary festivals, appeared on television, published political essays, churned out novels with regularity, mingled with celebrities, and even took to Twitter with an unlikely enthusiasm.

The assault on Rushdie came as a cruel reminder that the past still casts a shadow. The young man suspected of stabbing the writer was not even born when The Satanic Verses was first published. He is unlikely to have read the novel, let alone grasped the attempt at magical realism.

For religious extremists, the facts scarcely matter. The perception of an insult is enough to warrant their murder.

In 1991, Rushdie’s Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, was killed in his office at the University of Tsukuba. Two years later, William Nygaard, Rushdie’s Norwegian publisher, was shot three times outside his home. He miraculously recovered.

In the days after the fatwa, Rushdie didn’t win universal sympathy. Norman Tebbit, one of Margaret Thatcher’s closest allies, denounced him in this newspaper as “an outstanding villain”. John Le Carré ignited a decades-long row between them, saying that “there is no law in life or nature that say that great religions may be insulted with impunity”.

VS Naipaul, a longtime rival, appeared to laugh off the fatwa, describing it as “an extreme form of literary criticism.” It was left to often left-wing writers like Tariq Ali, Harold Pinter, Christopher Hitchens, Edward Said and Hanif Kureishi to defend him.

Rushdie himself was appalled by the accusation The Satanic Verses represented an insult. As he wrote in his memoir, Joseph Anton, the book took four years to write and he “can insult people a lot faster than that.” Why, he asked, would have spent a tenth of his life up to that point to create something “as crude as an insult”?

Rushdie wanted to be seen as a serious writer who had produced a serious book – not, as some had claimed, for personal gain. As far as Rushdie was concerned, he wrote, this was the least political of this recent three books – and “essentially admiring of the Prophet of Islam and even respectful toward him.” What Rushdie couldn’t fathom was that his book was not treated as a piece of art, but became hostage to a conflict.

The Rushdie fatwa appeared at a moment of a renewed clash between parts of the West and the Muslim world. The fatwa was a cynical attempt by a fossilised Ayatollah to weaponise the divisions between them and rouse the anger of the faithful. It worked. Angry protests erupted in different Muslim-majority countries.

✕ Author Salman Rushdie attacked on stage in New York

The book was torched on the streets of Bradford and banned in India. Bookstores were firebombed, leading others to withdraw it from their shelves. Rushdie himself was forced into hiding for many years, moving from place to place, kept company by officers from Scotland Yard, whose overbearing presence he resented.

The cry of blasphemy remains a powerful incitement to fanatical violence. On the day Rushdie was attacked, a member of the minority Ahmadi sect was stabbed to death in the Pakistani town of Rabwah. Mobs have taken to the streets of Bangladesh, Pakistan, Egypt, and Indonesia to avenge an alleged insult to Islam or the Prophet Muhammad. In countries where most people are Muslims, they somehow claim that their faith is imperilled.

To maintain this violent hysteria, they insist that an offence has been committed and that punishment must follow. They are never open to hearing that the allegation was false, or that evidence doesn’t exist, or that mere words should never be met with violence.

These attitudes were always limited to a minority in the Muslim world, but they were all too often seized upon as proof of an inherently intolerant “culture” that was irreconcilable to Western freedoms.

(EPA)

One of the tragedies of the last couple of decades is that there was never a serious reckoning with the issues that the Rushdie affair surfaced: the divisions in the Muslim world between those who fought for an open society and those who opposed them, the role of Western-backed dictators in stifling those freedoms, the anger at often Western-backed wars that were visited upon many Muslim-majority countries, or the intolerance that Muslims faced in the West.

Ironically, it was Rushdie who illuminated these divisions in his earlier work. The job of literature, Rushdie once wrote, is to stimulate “understanding, sympathy and identification with people not like oneself.” Rushdie was a fierce critic of British racism, the subject of a searing lecture broadcast on Channel Four called “The New Empire Within”.

His most famous book, Midnight’s Children, is a magisterial assault on the legacy of colonialism, the fecklessness of South Asia’s ruling classes, and the violent chauvinisms that created the three separate countries of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. His 1983 novel Shame laid bare the three-way fight between Pakistan’s corrupt politicians, its cruel mullahs, and its conniving generals that continues to this day.

It is hard not to reach the conclusion that the fatwa changed Rushdie as a writer, even diminished him. He continued to write essays and novels, some of them very brave defences of his writing and of free inquiry. But they rarely took on the great themes that his earlier work explored.

Some of his critics were ferocious. In a review of his memoir, Zoe Heller noted the many flaws he freely exhibited, including his “bombast” and “shuddering hauteur”. But today’s attack should force us all to think about what it means to live with a death sentence hanging over a writer for decades, one that could be carried out at any time.

Omar Waraich covered Pakistan for ‘The Independent ‘ from 2007-2016?