“I am informing all brave Muslims of the world that the author of The Satanic Verses […] along with all the editors and publishers aware of its contents, are condemned to death. I call on all valiant Muslims wherever they may be in the world to kill them without delay […] Whoever is killed in this cause will be a martyr, God willing.”

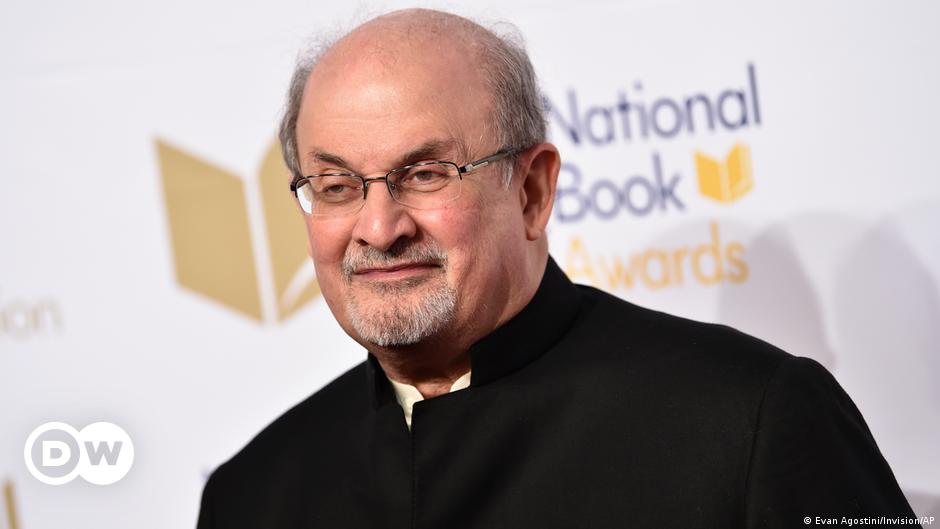

On February 14, 1989, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s supreme leader, issued a fatwa — a religious decree — calling for the murder of the writer Salman Rushdie. On August 12, 2022, more than 33 years after this dubious fatwa, the author was attacked and stabbed multiple times at an event in the US state of New York. The police arrested suspect Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old US citizen with Lebanese origins, and charged him with attempted murder and assault, to which he pleaded not guilty in a New York court. Rushdie suffered severe injuries but survived the attack.

Was the suspect aware of the context?

Though it would seem natural to view Khomeini’s death sentence as directly responsible for this heinous act, there are other, more important questions: Did the alleged attacker even know the political context of this fateful fatwa? After all, he was born almost 10 years after the leader of the Iranian revolution died. His apparent admiration for Khomeini does not provide an answer.

Loay Mudhoon is the head of qantara.de, which promotes dialogue with the Islamic world

Nor can we assume that Matar, who grew up in a typical US Muslim family without any affinity for radical Islam, was in a position to know of the fragile position of the controversial fatwa in Islamic states. But first things first.

Three decades after Khomeini issued his fatwa, it is clear that it was a clear political instrumentalization of Islam. The revolutionary leader used the anger of the masses against Rushdie’s novel “The Satanic Verses,” which had supposedly offended the Prophet Muhammad, to style himself as a defender of Islam — particularly outside of Shiite Iran.

Leader of all Islam?

Khomeini’s political calculation aimed to liberate his Shiite “Islamic Revolution” from isolation within the larger Islamic world and to recommend it as a revolutionary model for all Muslims, including Sunnis, with him as the “Islamic pope!” Furthermore, he wanted to use the pan-Islamic waves of indignation over the “Satanic Verses” for his fight against the United States, which he referred to as the “Great Satan,” to concretize his anti-Western interests.

Rushdie’s alleged attacker was probably unaware of the theological and intellectual isolation of the man who issued the fatwa. Numerous Islamic states and scholars objected to Khomeini’s presumption of speaking in the name of all Muslims. Most Islamic authorities also rejected the fatwa with regard to Sharia law, arguing that there was no basis in the Quran for punishments over blasphemy or insulting the Prophet Muhammad.

In an interview with the tabloid New York Post, Matar said he had only read “two pages” of “The Satanic Verses.” This recalls the attack on Egyptian writer and Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz, who was almost stabbed to death in front of his house in Cairo in October 1994. Also an Islamist extremist, his attacker later said in court that he did not know any of Mahfouz’s books.

Salman Rushdie – A marked man

What remains is the awareness that the poison of radical Islamism continues to have an effect that transcends borders, and even removes them — especially when questionable “fatwas” legitimize violence. In the interview, Matar said he respected Kohmeini and believed Rushdie attacked Islam and was not a good person. The Post reported that, on the advice of his lawyer, he did not comment on whether the fatwa inspired him to take any action. Unfortunately, the danger of a single person taking violent action remains omnipresent in our interconnected world.

Meanwhile, Iran has blamed Rushdie himself for the crime. This is contemptible — after all, the regime has kept the fatwa in place. At this point, there is no need to evaluate the reactions of the Iranian media, which are under the control of religious hardliners. Paradoxically, however, the failed assassination attempt could be a political inconvenience for the decision-makers in Tehran, as it could put a strain on negotiations for a new nuclear agreement and weaken Iran’s position.

This op-ed was originally written in German.