The source of the files claims to have hacked, downloaded and decrypted them from a number of police computer servers in Xinjiang, before passing them to Dr Adrian Zenz, a scholar at the US-based Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation who has previously been sanctioned by the Chinese government for his influential research on Xinjiang.

Dr Zenz then shared them with the BBC, and although we were able to contact the source directly, they were unwilling to reveal anything about their identity or whereabouts.

None of the hacked documents is dated beyond the end of 2018, possibly as the result of a directive issued in early 2019 tightening Xinjiang’s encryption standards. That may have placed any subsequent files beyond the reach of the hacker.

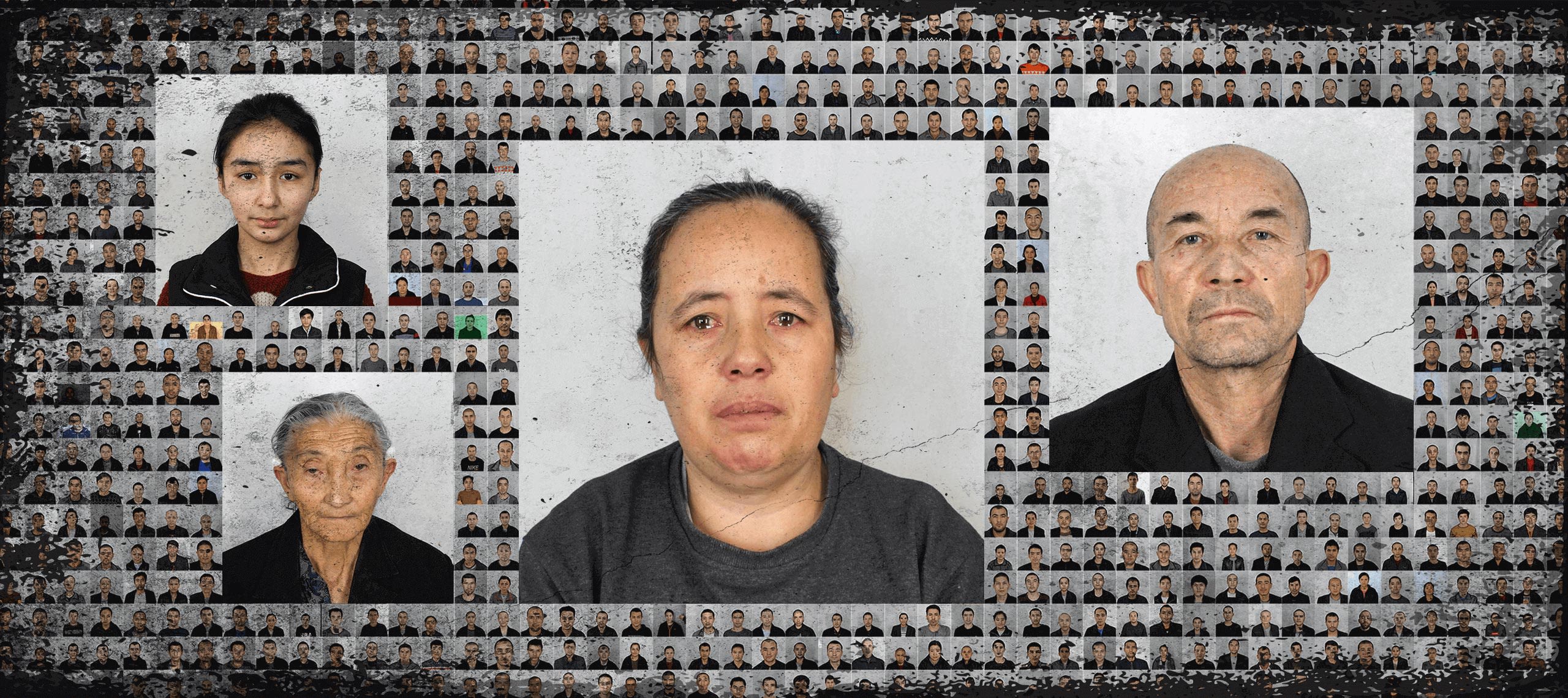

Dr Zenz has written a peer-reviewed paper on the Xinjiang Police Files for the Journal of the European Association for Chinese Studies and he has placed the full set of detainee images and some of the other evidence online.

“The material is unredacted, it’s raw, it’s unmitigated, it’s diverse. We have everything,” he told the BBC.

“We have confidential documents. We have speech transcripts where leaders freely talk about what they really think. We have spreadsheets. We have images. It’s completely unprecedented and it blows apart the Chinese propaganda veneer.”

The Xinjiang Police Files contain another set of documents that go even further than the detainee photographs in exposing the prison-like nature of the re-education camps that China insists are “vocational schools”.

Xinjiang Police Files: Inside a Chinese internment camp

A set of internal police protocols describes the routine use of armed officers in all areas of the camps, the positioning of machine guns and sniper rifles in the watchtowers, and the existence of a shoot-to-kill policy for those trying to escape.

Blindfolds, handcuffs and shackles are mandatory for any “student” being transferred between facilities or even to hospital.

For decades, Xinjiang has seen a cycle of simmering separatism, sporadic violence and tightening government control.

But in 2013 and 2014, two deadly attacks targeting pedestrians and commuters in Beijing and the southern Chinese city of Kunming – blamed by the government on Uyghur separatists and radical Islamists – prompted a dramatic shift in policy.

The state began to see Uyghur culture itself as the problem and, within a few years, hundreds of giant re-education camps began to appear on satellite photos, to which Uyghurs were sent without trial.

Xinjiang’s formal prison system has also been massively expanded as another method for controlling Uyghur identity – particularly in the face of mounting international criticism over the lack of legal process in the camps.