Berlin, Germany – Just a few weeks before the opening of documenta 15, one of the world’s most prestigious art events, Palestinian artist Yazan Khalili received a WhatsApp message telling him there had been a break-in at his exhibition space.

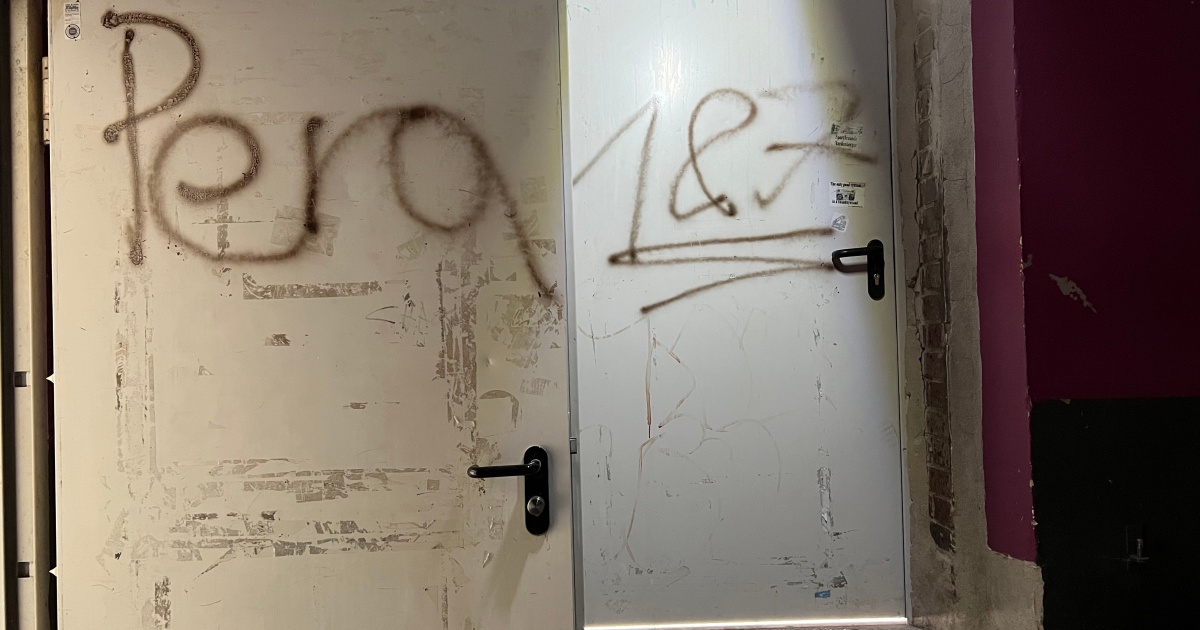

He arrived at the room in a former nightclub in Kassel, central Germany, to find the intruders had let off a fire extinguisher and spray-painted what appeared to be death threats on the walls.

The perpetrators remain unknown, but the vandalism marked an alarming escalation in a controversy that has been rumbling in German media for months, after an obscure blog in January accused artists and organisers of documenta, in particular Khalili and his The Question of Funding collective, of anti-Semitism.

This year’s documenta – which runs from June 18 to September 25, 2022 – is curated by Indonesian art collective Ruangrupa, which has broken with tradition by using a collaborative format and inviting a wider range of participants from the Global South than previous editions of the quinquennial exhibition.

But the debate surrounding the event has raised questions about whether Germany’s approach to combating anti-Semitism discriminates against Palestinians and supporters of Palestinian rights, and limits artistic freedom.

“There was so much emotion and fear,” Khalili told Al Jazeera. ”This has been building since January – lots of hostile, aggressive media campaigns … against me and other Palestinian artists, or artists who showed support for Palestine.”

Documenta organisers interpreted the “187” sprayed on the walls as a reference to murder in California’s penal code, and “Peralta” to Spanish neo-Nazi Isabel Peralta, who has links to the extreme right in Germany.

The incident on the night of May 28 has led to concerns for the safety of artists in Kassel, which is about a two-hour drive from Hanau, where a right-wing extremist murdered nine people in a racist killing spree in 2020.

“There is a line that has been crossed. Before all these defamations and aggressions were digital. Now they have become physical,” said artist Yasmine el-Sabbagh, whose work involving an audio-visual archive of life in the Palestinian refugee camp Burj al-Shamali will feature in documenta. She was named in the blog post in January.

In response to the targeting of Khalili’s exhibition space, documenta said it had filed a criminal complaint with police and would step up security at the event.

“We are united against the racist attacks that started this sequence of events,” Ruangrupa said in a statement published on Friday.

“We also express our dismay and disappointment at the amplification that the original baseless blog post of disinformation and manipulated content received in some of the mainstream media. We denounce the media participation in these smear campaigns,” it added.

Germany’s support for Israel is a cornerstone of its post-war political identity and was named a raison d’etat by former Chancellor Angela Merkel.

In 2019, the German parliament declared the Boycott, Divest and Sanctions (BDS) movement, which advocates an economic and cultural boycott of Israel over its occupation of Palestine, to be explicitly “anti-Semitic”. In the years since, supporters of BDS have been stripped of awards, disinvited from events, and publicly denounced as anti-Semites.

Germany is home to Europe’s largest population of Palestinians, but many find the political climate is becoming increasingly hostile towards them.

“You are suspected of not sharing the German memory culture, the consensus on Holocaust memory,” said Palestinian-German academic Sami Khatib. “And of course you’re scrutinised for that.”

In May, Berlin police prohibited all Palestinian rallies on the weekend of the anniversary of the Nakba – the ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948 – on the grounds that there was a high risk of anti-Semitic behaviour, which organisers denied. This included a vigil organised by a Jewish group for Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, who was killed by Israeli security forces in May.

“From a German perspective Palestinians are problematic; their very existence is problematic,” said Khatib. “This is not all of Germany, but this is what you get from major journals, certain politicians, and also certain NGOs who are engaged in a civil society fight against anti-Semitism. And today, this fight is mostly against Palestinians.”

The recent targeting of Palestinian artists at documenta began when the news blog Ruhrbarone published an anonymously authored post sourced from the Kassel Alliance against Anti-Semitism, a group that identifies as part of the “anti-German” scene.

The anti-Germans are a left-wing sect that identify closely with the State of Israel and are staunchly Islamophobic.

The blog post accused several figures involved in documenta of anti-Semitism for their support of BDS or signing of petitions critical of Israel. It focused particularly on Khalili and The Question of Funding, and their connection to the Khalil al-Sakakini Cultural Centre in Ramallah. The author painted al-Sakakini, an Arab nationalist intellectual born in the 1870s, as a Nazi sympathiser – an account rebutted by historian Jens Hansen.

The accusations were picked up and repeated by major German-language newspapers from across the political spectrum, including left-wing Die Tageszeitung, liberal Die Zeit and conservative Die Welt – none of which initially contacted Khalili, he said.

Though several newspaper contributions and statements from public figures, including the head of the Anne Frank Educational Centre, have dismissed the claims of anti-Semitism made by the blog post, the issue has continued to resurface, even dragging in Germany’s culture minister Claudia Roth.

In April, stickers were posted on Ruangrupa’s headquarters, which read “Freedom instead of Islam! No compromises with barbarism!” and “Solidarity with Israel”.

Ruangrupa pushed back against what it called “bad-faith” attacks in a public statement, saying that the “alliance” was in fact one person, whose allegations were totally false. Ruangrupa has organised a series of online talks to discuss the “role of art and artistic freedom in the face of rising anti-Semitism, racism, and Islamophobia”, which featured artists Eyal Weizman and Hito Steyerl. After the president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany wrote to Roth to criticise the composition of the panels, Ruangrupa scrapped the series and said it would allow the event to speak for itself.

“It’s so obvious that it’s a smear campaign from the very beginning, that all these accusations are not based on anything. They are incendiary,” said el-Sabbagh, adding that many news outlets failed to scrutinise the blog’s racist language.

“It’s really shocking to see that mainstream media doesn’t reflect critically on this. Many of them just pick this up to put more oil on fire.”

In a statement published on Friday, the Kassel Alliance against Anti-Semitism denied any connection with the vandalism, which it suggests was committed by local youths and was not political, but referred to the Hamburg hip-hop group 187 Strassenbande and unknown Filipino rapper RJ Peralto, who has no obvious connection to Germany.

The group did not claim responsibility for the stickers, but said they were a legitimate form of solidarity with Israel. “We make no secret of the fact that we are critical of Islam,” it added.

Without a lobby to defend them, Palestinians make an easy target for German media outlets who wish to associate them with anti-Semitism, said Khatib.

“It’s kind of a public performance of moral goodness, of being self-righteous.”

Khalili initially offered interviews to the German press to defend himself, but found the tone of questioning from journalists to be frequently hostile or presumptive of his guilt. One asked him whether the curators made a mistake in inviting his collective – “a humiliating question”, he said.

Though he had exhibited several times before in Germany without a problem, he now found himself spending countless hours grappling with a crisis into which the collective had been thrown. The art community in Kassel has been incredibly supportive, he said, but the ordeal has been exhausting.

Members of the collective have had to rethink the exhibition, which will examine alternative economic structures to the institutional model of funding art in Palestine, to ensure that individuals and communities in Palestine who are involved will be protected.

“I think I was too innocent thinking that we can come and express our work,” Khalili said.