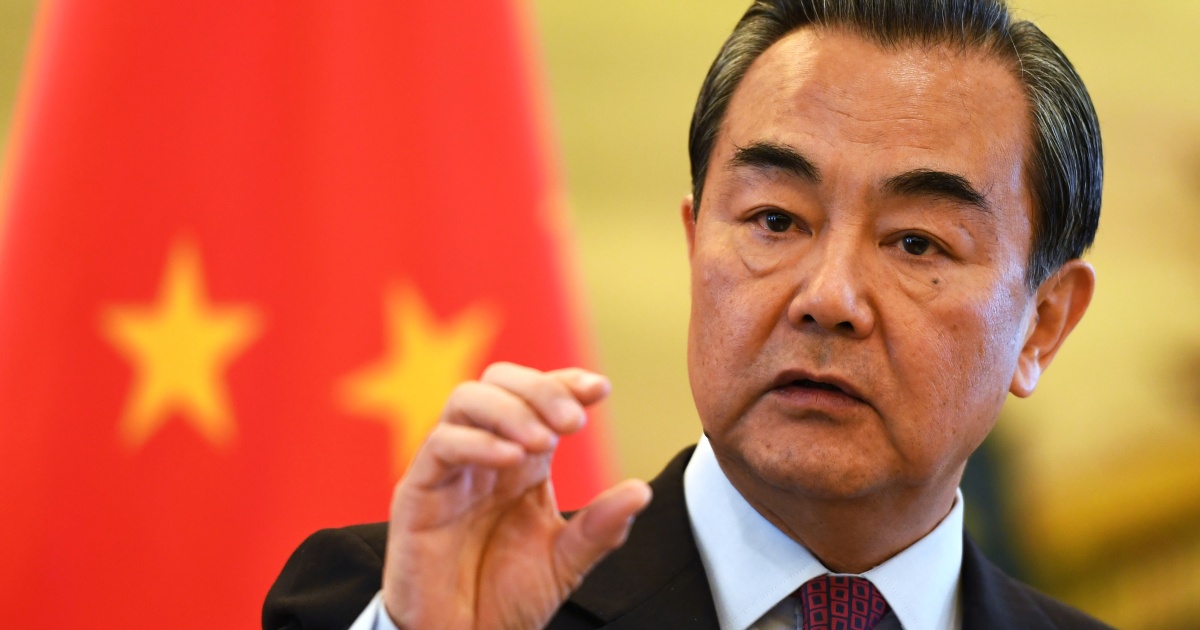

Harmonious humming voices accompany the image of a young man with a baby in his arms, sitting between tall grass and looking into the distance at the Johannesburg skyline. The man goes by the name of Tsotsi, a synonym for gangster, and he is the main protagonist of the film of the same name.

In 2006, the South African production “Tsotsi” won the Oscar for best foreign language film, one of the rare times the award went to an African country.

Ever since its creation in 1948, the coveted Academy Award for the best international feature film — the category known as best foreign language film prior to 2020 — has overwhelmingly been awarded to European productions.

In the past 15 years, non-European films have often won the Oscar, but regions such as Asia, as well as Latin America and the Caribbean remain underrepresented. In the nearly 75 years of the awards’ history, only three Oscars in this category have ever gone to an African country.

North America excludes the US in this category

The three African exceptions

Of the three African prize-winners, two were French co-productions: “Z” and “Black and White in Color.” The co-productions emerged from the ongoing ties between France and two of its former colonies, Algeria and the Ivory Coast, and the films benefited from the great influence of the French film lobby in Hollywood.

It was not until 2006 that a non-French-language film from Africa won an Academy Award, with “Tsotsi,” by South African director Gavin Hood.

But the success of “Tsotsi” is not entirely a coincidence either, as Steve Ayorinde, a renowned Nigerian film critic who has been a juror at international film festivals such as Cannes, Berlin and Toronto, points out. Many of the South African films that gain international attention are directed by white filmmakers, as was the case for “Tsotsi” director Gavin Hood.

Non-European winners of the Oscar for best foreign film 1970: Algeria — ‘Z’ by Costa Gavras The first time an African country won the Oscar for best foreign language film was in 1970, with “Z.” The France-Algeria co-production was one of the top five best-grossing non-English language films in the US that year. The thinly-fictionalized account of a Greek politician’s assassination portrayed how the army and state tried to cover up the case, until a persistent judge uncovered the truth.

Non-European winners of the Oscar for best foreign film 1977: Ivory Coast — ‘Black and White in Color’ by Jean-Jacques Annaud The Ivory Coast-France co-production by French director Jean-Jacques Annaud is a war comedy with a clear anti-military message. Set during the First World War, it is about French colonialists in Cameroon who are attacking the neighboring German colony.

Non-European winners of the Oscar for best foreign film 2006: South Africa — ‘Tsotsi’ by Gavin Hood With dialogues in Setswana, Zulu, Sesotho and Afrikaans, the South African production by Gavin Hood is the first and to date only non-French-language African film to have won the best foreign film Oscar. The drama follows a South African criminal in Johannesburg who finds redemption by taking care of the baby of one of his victims.

Non-European winners of the Oscar for best foreign film 1951: Japan — ‘Rashomon’ by Akira Kurosawa The film deals with the rape of a woman and the murder of her samurai husband, told from the perspective of four witnesses whose accounts widely differ. “Rashomon” explores the complexity of truth and human nature. The film was the first non-European film to win an Oscar for best foreign language film.

Non-European winners of the Oscar for best foreign film 1986: Argentina — ‘The official story’ by Luis Puenzo Set in the final months of Argentina’s military dictatorship in 1983, the film follows a family of three consisting of a history teacher, her husband and their adopted daughter. They lead a relaxed and comfortable life, until the mother attempts to find out the identity of her daughter’s biological mother — and learns about the authoritarian regime’s forced disappearances.

Non-European winners of the Oscar for best foreign film 2001: Taiwan — ‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’ by Ang Lee The action takes place in 19th-century Qing Dynasty China. A warrior, Master Li, gives his sword to the woman he loves, who is also a fighter. She is to hand over the sword to his friend in Beijing. However, the sword is stolen and Master Li sets out to recover it. The film won numerous awards and broke box office records.

Non-European winners of the Oscar for best foreign film 2017: Iran — ‘The Salesman’ by Asghar Farhadi A couple moves into a new house. The woman is attacked and injured by an intruder there, leaving her severely traumatized. Her husband then goes in search of the culprit, despite his wife’s objections. In protest against Donald Trump’s so-called “Muslim ban,” director Asghar Farhadi did not attend the Oscars to pick up his prize for best foreign language film. Author: Julia Merk

According to Ayorinde, lobbying is an important profit factor: “Yes, a number of African films are always on the sidelines of major festivals. But then, who pushes them? Without collaborations, without support, without a major European and American institution or .roduction companies investing in such a film, it will be difficult to market such a film to the world.”

American or European filmmakers, for example, are much better at this. So it’s not surprising that 78% of the winners in the best international film category are European.

France and Italy are the perennial favorites, with more than half of the wins. Both countries have a strong influence in Hollywood, while films from African, Asian or Latin American and the Caribbean countries remain invisible.

Bollywood also snubbed by Hollywood

Half of the Asian-winning films are Japanese productions. Despite the size of Bollywood’s film industry, India has never won the best international film award.

Another reason is the lack of financial means to promote Indian films to the Academy, says Namrata Joshi, an Indian film critic and author who has served on international film festivals juries in Toronto, Moscow and Cluj.

“The Oscars are just a marketing game,” she points out, adding that anyone who can attract the attention of the Academy with good marketing has a better chance of being nominated.

According to Joshi, another barrier is the content of the films. Indian films are often too melodramatic for a global audience or contain too many music and dance scenes.

Bollywood has been shaping the image of Indian cinema abroad.

“It is important to break through these expectations because Indian cinema is not uniform. The diversity is immense, like India itself: India is like Europe, with so many languages and cultures. Bollywood does not describe the entire Indian film industry,” says Joshi.

Several barriers to gaining the Academy’s recognition

That African films are underrepresented at the awards ceremony is not because there are no good films. According to Ayorinde, several other factors come into play. It is very difficult to gain international attention, let alone a nomination, without funding, collaboration or technical support from Western institutions.

Language also plays an important role: European films, particularly those made in languages such as German, French, Spanish or Italian, have, in a way “an advantage because they are already in international languages,” says Ayorinde, who points out that those who will judge the films might already familiar with those languages; this is not the case for African languages such as Kiswahili or Zulu.

Even though Nigeria’s internationally renowned Nollywood industry produces around 2,500 films a year, it hasn’t won a single foreign film Academy Award.

Nollywood productions often do not meet the technical requirements of a cinema film since the focus is on home television. According to Ayorinde, streaming services like Netflix could change the situation significantly. Netflix is raising the bar, he says, by requiring cinematic standards even for films made for home viewing.

Watch video 02:43 Nollywood: Nigeria’s film industry gets streaming boost

For its original productions, Netflix pays enough to reach such standards. However, whether this will continue depends on the number of subscriptions Netflix can gain from Nigeria — and Africa in general.

African films could then perhaps gain international attention and appreciation through Netflix.

But even if the Nollywood productions improve their quality, this does not necessarily increase the chances of an Oscar nomination or win.

The Academy still requires a film to have a theatrical release to be nominated, which currently excludes Nollywood productions.

Steps taken by the Academy towards equal opportunities

Joshi and Ayorinde have seen the Academy’s efforts towards more diversity in recent years.

However, such a fundamental change does not happen overnight, says Joshi: “I think there should be a curiosity and attempt to try and understand cinema world over.” She believes that things will progressively change with the current efforts towards diversity representation.

That more people from India are now part of the Academy jury is an important first step, says the Indian film critic.

Another big step towards more equal opportunities for underrepresented countries would be to change the admission requirements.

Ayorinde points out more game-changing criteria: The Academy should abolish a theatrical release requirement, especially now that platforms such Netflix and Amazon Prime are transforming the film industry and leading to more high-quality films being produced for streaming. He also recommends creating more categories for non-English language films.

Ayorinde, like Joshi, sees the stronger representation of underrepresented regions among the voting members as very important.

The Academy has not responded to DW inquiries about the lack of representation of Africa, planned reforms to improve fairness, and the importance of marketing and lobbying.

Ayorinde’s proposed changes would give more non-English language films a chance to qualify for the competition. He believes that the overall quality of the films at the Oscars would not deteriorate: “The good ones will always stand out.”

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Tsitsi Dangarembga Dangarembga is not only a filmmaker but also successfully writes novels and screenplays, including for the film 1993 “Neria” that went on to become the most-watched film in Zimbabwe. In 2020, Dangarembga was arrested in Harare at a protest against government corruption and still faces trial a year later.

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Wanuri Kahiu Born in Nairobi in 1980, the director had a global cinema success with her 2018 film “Rafiki.” The first Kenyan film shown at the Cannes Film Festival, it portrays a love affair between two young Kenyan women and was banned in her home country. Kahui is now off to Hollywood, where she will direct “The Thing about Jellyfish,” based on the acclaimed novel by Ali Benjamin.

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Kemi Adetiba The Nigerian filmmaker, who also makes television series and music videos, is a big name in Nollywood — which is what people call Nigerian cinema, the second most productive in the world after Indian film. Commercially, Adetiba’s feature films are hugely successful. She is producing her next film, a sequel to her blockbuster “King of Boys,” exclusively for Netflix.

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Kunle Afolayan The Nigerian director is one of the most important representatives of the new Nigerian cinema (“New Nollywood”), which is characterized by narrative complexity, a new aesthetic — and a much bigger budget. Afolayan’s thriller “The Figurine — Araromire” (2009), one of Nigeria’s most commercially successful films, is considered to have launched the movement.

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Abderrahmane Sissako Sissako’s films deal with topics including globalization, terrorism and exile. Born in Mauritania and raised in Mali, the film director and producer is considered one of the best-known filmmakers from sub-Saharan Africa. His 2014 film “Timbuktu” was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars and won several prizes at France’s Cesar Awards as well as at the Cannes Film Festival.

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Philippe Lacote The film director from the Ivory Coast most recently premiered “La Nuit des Roies” (2020) at the Venice International Film Festival. The film, reminiscent of the stories from the “One Thousand and One Nights” Arabian folk takes, tells the story of convicted criminal named Zama who becomes a convincing storyteller in order to survive at La Maca prison in the Ivory Coast capital, Abidjan.

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Macherie Ekwa Bahango Promising new talent: The 27-year-old director from the Democratic Republic of Congo saw her film “Maki’La” debut at the 2018 Berlin Film Festival. The young self-taught director spent three years working on her first feature film, which is the story of a group of street children in Kinshasa. The film won top prize at the Ecrans Noirs African film festival in Cameroon.

Contemporary African filmmakers: Names to remember Moussa Toure Moussa Toure is a Senegalese film director, producer and screenwriter and has long been a major figure in African cinema. His feature films and documentaries are often political. Toure describes his 2012 film “La Pirogue,” which tells the story of refugees’ journey by boat from Africa to Europe, as a “slap in the face of the Senegalese government.” Author: Maria John Sánchez

This article was originally written in German.