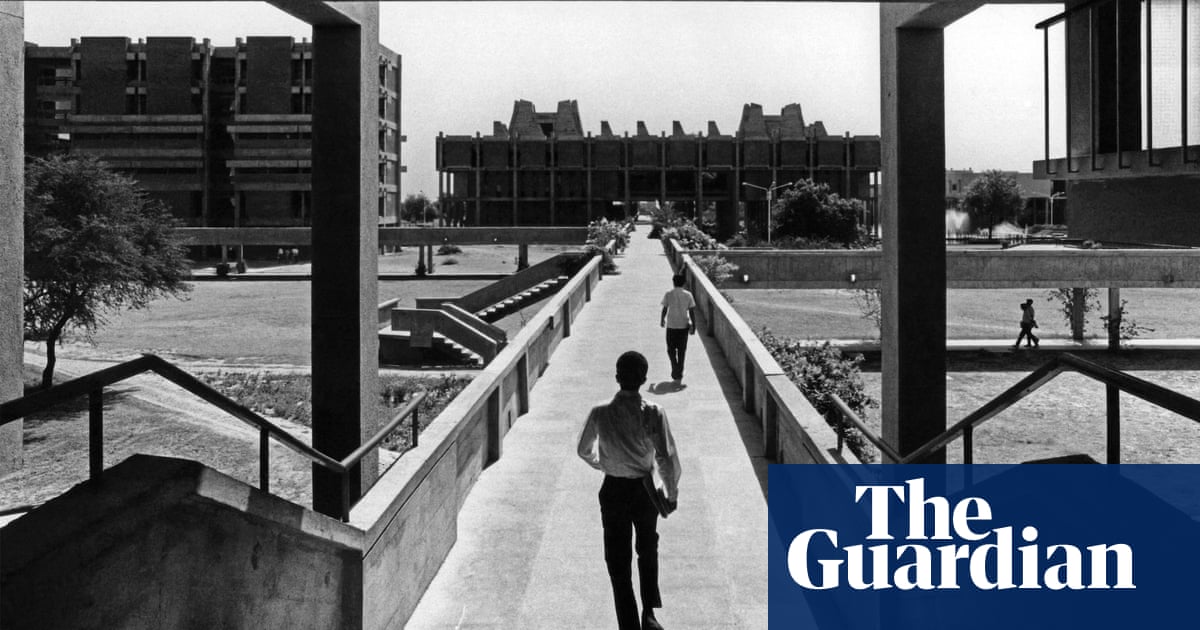

Show caption Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India. Photograph: Kanvinde Archives Architecture ‘They were transforming their countries’: South Asian architecture after British rule A MoMA exhibition takes a new look at the modernist structures that defined Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka after independence Matt Shaw Tue 22 Feb 2022 15.30 GMT Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share via Email

Light lands softly on concrete walls in a series of silver gelatin prints by an unknown photographer. These small, souvenir-like snapshots give glimpses into the houses of Sri Lanka’s first female architect, Minette de Silva. Here, there are no architectural drawings or models – those have been lost to time. What we see are the personal artifacts of De Silva’s mentee Anuradha Mathur – documents that have been newly uncovered as part of the exhibition The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985, at the Museum of Modern Art.

De Silva’s work – shown though this unconventional medium from an unconventional source – sheds light on the architect’s regional modernist architecture that has been largely ignored by institutions in the west. It is among many such materials now being brought to light both literally and metaphorically.

The Project of Independence is a sharply curated collection of about 200 archival and commissioned works, including contemporary photos by Randhir Singh and models by students at Cooper Union. For the first time, the public can see the architecture of “the idealistic societal visions and emancipatory politics of the post-independence period” of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

“They were transforming their countries according to a specific societal and political progressivism,” MoMA chief curator Martino Stierli said. “We wanted to ask, ‘How was this utopian vision grounded in the lives of everyday people?’”

Directly after the end of British colonial rule in 1947, South Asian architects used modern architecture to express the self-determination and emancipation of the post-colonial era. Focusing on a specific set of local modernist architects, the exhibition shows a clear break from the British traditionalist architects whose designs projected imperial power.

Hall of Nations, Delhi. Photograph: arhuber/GuardianWitness

“Often, expressions of modernism are presented as derivative of the west. However, they have their own unique translations and adaptations that are specific of the places they are coming from,” Stierli and co-curator Anoma Pieris explained. “It is not a mirror of the west. It has relevance and significance on its own.”

Perhaps the clearest example the new global technologies marrying local traditions and aesthetics was the recently demolished Hall of Nations in New Delhi, by architect Raj Rewal and engineer Mahendra Raj. Built between 1970 and 1972 for the Asia 72 international trade fair commemorating the 25th anniversary of India’s independence, the multifunctional exhibition space showcased the participating countries under a unique diagrid space from structure made from concrete.

Space frames could be considered the pinnacle of modernist innovation in construction techniques. Providing extremely longs spans under lightweight, mass-producible 3D-grid structures, space frames could theoretically cover the globe in flexible, almost uninterrupted space. They represent the innovative engineering and democratic ideals of global modernism.

At the Hall of Nations, this globe-spanning technology – usually made of steel – was remarkably built with cast in situ concrete, adapting a universal form to local building techniques and accommodating local materials and labor. The decision to use concrete was twofold: cheap local labor, and high transportation costs of shipping large prefab steel elements on the underdeveloped roads of the newly formed nation.

Hindustan Lever Pavilion, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, India. 1961. Demolished. Charles Correa and Mahendra Raj. Photograph: Mahendra Raj Archives

The Hall’s structurally expressive frame is a symbol of a technologically and socially progressive Indian society, while the use of concrete represents self-sufficient independence. It is a clear articulation of the hybridization of European and non-western thought, a recurring theme in the exhibition. This process is captured in an atypical format: an Associated Press film clip of the Hall of Nations under construction is thought to be the only video documentation of the construction of the building, which was sadly demolished in 2017.

New architectural languages and solutions paralleled the building of new institutions. This was the first generation of South Asian architects who saw themselves as connected to an international conversation on their own terms. The Hall of Nations brought together international participants under one roof, signaling India as a cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic, multicultural nation-state which had been established under the country’s first post-colonial prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, years before.

The four countries were part of the 85-country non-aligned movement, which resisted taking sides in the cold war, instead taking aid from both sides in a show of self-determination, as well as sharing technology and resources in third world solidarity.

Chittagong University, Chittagong, East Pakistan (Bangladesh). Photograph: Photograph: Randhir Singh

Founded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the Indian International Center was designed by American architect Joseph Allen Stein with environmentally conscious and socially resonant features such as fired clay screens (jali) to create an international hub that would gather visitors and a local elite to build an international conversation. Reinterpreted historic forms connected locally, but materials – concrete, stone and brick – were sourced from around the world.

The post-colonial period wasn’t without struggles, however. The end of British colonial rule and subsequent “partitioning”, or violent delineation of newly formed countries, caused the largest refugee crisis in history, resulting in a building boom. Enormous government-sponsored mass housing blocks were built in a relatively straightforward modernist way, but adapting to local climate and cultural conditions.

In Pakistan, the newly formed Muslim-majority government sought ways to articulate a cosmopolitanism in an Islamic state. Pakistani architect Yasmeen Lari’s Anguri Bagh housing demonstrates a turn away from “instant Islamic” architecture, which she saw as an appropriated form. Lari opted instead for a more decentralized and organic aggregation of units designed with direct participation of the previously marginalized community. As with de Silva’s houses, archival materials were not available. The curators instead relied on reproductions of plans and photos from the Aga Khan Foundation.

The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985 at the Museum of Modern Art was curated by Stierli, Pieris and Sean Anderson, with Evangelos Kotsioris. It is a major contribution to the continuing global project of uncovering the ways in which modernism was deployed in contexts around the world, helping to realize social and political projects through inventive and context-specific formal and material conditions.

The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985 is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York until 2 July