In the summer of 1988, a dozen or so men gathered in the sweltering Pakistani frontier town of Peshawar. Across the border in Afghanistan, the war was reaching a bloody climax, as hundreds of thousands of local mujahideen took on the Soviet occupiers and their local auxiliaries.

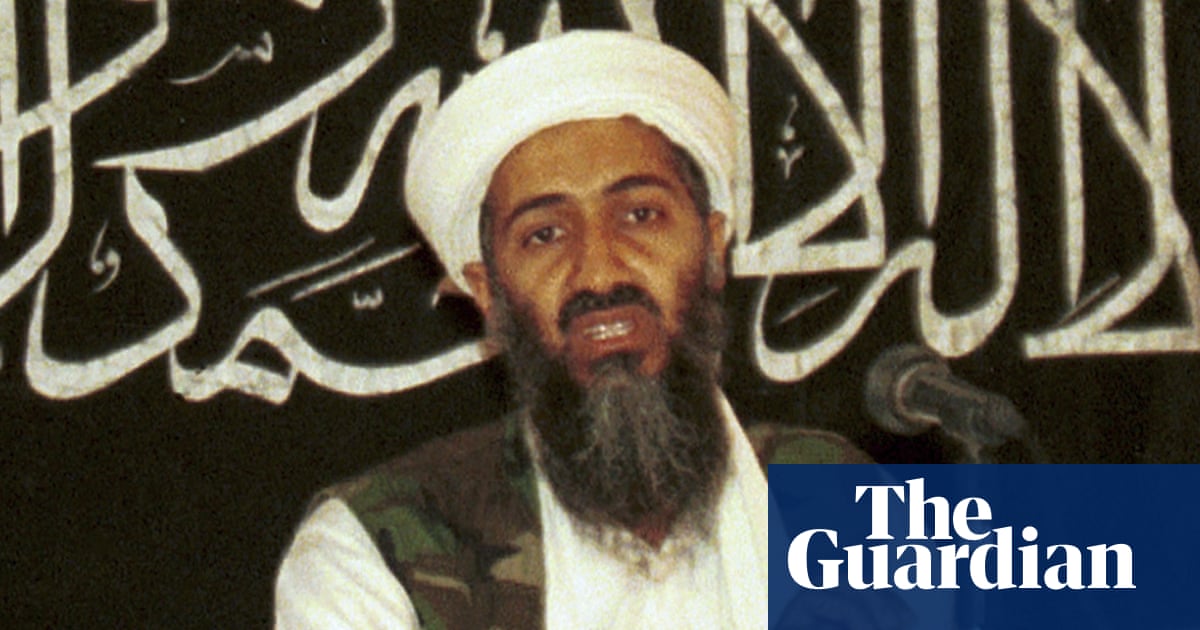

The men, who probably met in one of the guesthouses that acted as offices and hostels for foreign visitors to Peshawar, were all from the Middle East. Most had been in Pakistan for several years but had played only a very marginal role in the bloody war raging to the west. But a handful had been with their de facto leader, a wealthy Saudi Arabian called Osama bin Laden, when he had fought off a Soviet attack on a base inside Afghanistan a year earlier.

They had come together to discuss various issues – administrative problems with the flow of financial and other aid from the Gulf, personal rivalries with senior leaders of the so-called “Afghan Arabs” based in Peshawar, and much more. But they also wanted to talk over a new project: the creation of a unit of committed and experienced Islamist fighters who could deploy to wherever Muslims needed their protection. The group would also be a vanguard who could attract further recruits and spread the radical views of its adherents. Its name would be al-Qaida.

Thirteen years later, al-Qaida and Bin Laden would be responsible for the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington, which caused 3,000 deaths. These led to Bush administration’s war on terror, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, a manhunt that led to the death of Bin Laden in 2011, and a multitude of seismic global consequences. Not since 1914, when the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand triggered the first world war, had a single attack by a single terrorist group had such an impact.

Twenty years after that attack, and al-Qaida is very much still with us. Research suggests that individual terrorist groups usually survive for between five and 10 years, or even less, so this is an undoubted achievement. To enjoy such longevity in the face of the most expensive, technologically-advanced and expansive effort ever made against a single group is more astonishing still. No one on this tragic anniversary is predicting the end of al-Qaida. So how have they done it?

Not since 1914, when the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo, triggered the first world war, had a single attack by a single terrorist group had such an impact. Photograph: Jason Szenes/EPA

The first obvious advantage enjoyed by al-Qaida has been the failures and weaknesses of its adversaries. The group’s propaganda has sought to portray local governments across the Islamic world as corrupt, incompetent, repressive and exclusive. This is not unfair criticism, and so makes al-Qaida’s argument that these flaws are due to a rejection of the true path shown by the holy texts and traditions of Islam resonate more easily.

The errors of those directing the campaign against al-Qaida have also helped enormously. In 2002, al-Qaida had lost its safe haven in Afghanistan and many of its members had been killed. The rest were scattered in neighbouring countries or on the run further afield. For two years after the 9/11 attack, as Osama bin Laden moved from safe house to safe house in Pakistan, al-Qaida was effectively rudderless. Though criminally indiscriminate, the CIA’s dragnet did bring in some major figures, and operations elsewhere scooped up many more.

But bellicose rhetoric, a failure to understand the diffuse and ideological nature of the threat and above all the invasion of Iraq restored the group’s fortunes. It distracted the attention of US policymakers and the resources of its security agencies. The war to oust Saddam Hussein, justified in part by a fallacious link between al-Qaida and the Iraqi regime, appeared to vindicate many of Bin Laden’s arguments and prompted a vast surge of anger across the Islamic world. It also opened a new front, which allowed al-Qaida to get back in the fight.

It did not allow al-Qaida to win, however. The wave of violence unleashed by militants through the middle of the post-9/11 decade aimed to terrorise enemies, radicalise existing members and mobilise new support. It may have achieved the first two goals – at least in part – but not the third. As each new campaign erupted in the Middle East – in Iraq, Jordan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia – the extremists lost any sympathy among the general population. By 2010, Bin Laden was so concerned about how the repeated massacres of other Muslims had tarnished the al-Qaida brand that he pondered changing its name – and sent out fierce injunctions to subordinates to dial down the violence. Once again, the pendulum was swinging against al-Qaida, but it would swing back again.

But 2011 was particularly bad for the group. Bin Laden was killed in a US special forces raid on his home in the northern Pakistani town of Abbottabad, and half a dozen other senior figures in the organisation died or were detained too.

In the weeks before his death Bin Laden worried that he, his organisation and their thinking had been marginalised by the upheaval of the Arab spring. The crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir square and elsewhere in the Middle East were shouting for democracy, not for a rigorous Islamic regime. In the end it was Bin Laden’s successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, an older Egyptian former paediatrician and veteran extremist who found a way to exploit the sudden chaos, and restore al-Qaida’s fortunes.

Ayman al-Zawahiri demonstrated an unsuspected strategic talent and ability to learn the lessons of previous decades. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

Zawahiri had an undistinguished career as an extremist leader, lacked charisma and was not well liked within either al-Qaida or the broader jihadist movement. But he immediately demonstrated an unsuspected strategic talent and ability to learn the lessons of previous decades. The main innovation of Bin Laden in the late 1990s had been to direct its full resources against the “far enemy” – the US and the west – not the “near enemy – local governments in the Middle East. Bin Laden’s first ventures in this direction had come when he had targeted US forces in Yemen in 1991, but matured seven years later with massive, lethal attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania swiftly followed by a maritime strike against a US warship in the Gulf of Aden. These efforts culminated in the 9/11 attacks, which were deeply controversial within his organisation and opposed by many of its secondary leaders.

Zawahiri turned away from this strategy, making it clear that the far enemy was no longer a priority, partly because such attacks had become much harder and partly because of the response they would be likely to provoke. He also moved al-Qaida away from its doctrine of “only jihad”, stressing the importance of building ties with local communities across the Islamic world which felt under threat.

If al-Qaida could provide protection, security, even governance, then it could build grassroots support and extend its reach. The new strategy soon brought results, bringing new influence and recruits in the Sahel, east Africa, Yemen and in Afghanistan, where a new effort was made to build ties with the Taliban, which would be of crucial importance a decade later.

Then, in 2014, a new challenge emerged: a breakaway group which rejected Zawahiri’s authority entirely. It first called itself the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, then, once it had seized a swath of land across those two countries and announced the establishment of a caliphate, simply Islamic State.

This could have been a disaster for al-Qaida. Islamic State was much quicker to exploit the opportunities offered by the stunning spread of social media and smartphones, and appeared to have already achieved the long-term goal that al-Qaida had been striving towards. But the brutality of the newcomers, combined with Zawahiri’s more pragmatic strategy, combined to give al-Qaida the makeover Bin Laden had pondered before his death.

Compared to Islamic State’s spectacular sadism, even al-Qaida seemed less bloodthirsty. A key text for both groups was a manual to jihad ambiguously entitled The Management of Savagery. The two interpreted its advice differently. Islamic State and its growing number of affiliates believed the title suggested the uses of extreme brutality while al-Qaida thought it meant the need to control violence. As Bin Laden had done, Zawahiri also steered his organisation away from both the sectarianism and the apocalyptic millenarianism of its rival. When Islamic State’s caliphate collapsed in 2019, al-Qaida was well positioned to claim the leadership of the global jihadist movement once again. It has not done this yet – and Islamic State still contests the role, sometimes violently – but has regained much ground. The fall of Afghanistan to its long-term allies, the Taliban, has provided a further boost.

Ten days after the Taliban seized Kabul, al-Qaida issued a statement congratulating the movement on its “great victory against the crusader alliance”, an echo of the first declarations of war on the west broadcast by Bin Laden 25 years before. This was on behalf of all Muslims, and a “prelude to the liberation of Palestine … the Levant, Somalia, Yemen, Kashmir”, the group said, underlining its global ambitions but also local focus. For the al-Qaida leadership, “the defeat of the US places the global jihad into a new phase”.

It is too early to tell if this last statement is true. But we can guess one thing.

Al-Qaida has survived 33 years because it has evolved. Throughout its bloody history, it has changed with the times. Despite the grand ambitions of its founders, the organisation was originally parochial in its focus, with Saudi Arabia, Bin Laden’s birthplace, prominent among its targets. To propagate its ideology, it sought to execute massive attacks that would get the attention of traditional media, then the sole way to reach a mass audience. Al-Qaida then turned on the far enemy and prosecuted a truly world-spanning campaign through a decade and a half that was characterised everywhere by unprecedented globalisation.

Their communications strategy was re-engineered to match the new capabilities of satellite networks, and the group took full advantage of the now ubiquitous internet to assist with management of a sprawling organisation and attack planning. Over the last 10 years, as that wave of globalisation has ebbed in the face of economic crises and resistance to the erosion of cultural identities, al-Qaida has evolved again, pivoting neatly to something much more local – and understood that in the new media environment, complex plots work less well than “leaderless” attacks inspired through social media.

The Arabic word chosen as a name for the group back in the late 1980s suggested many things: an organising principle or the solid foundation of a building are two possible interpretations – but above all a military base. This was how these men had referred to the fortified camp from which they had just repulsed the Soviets in the first true battle of their campaign. It was also how irregular fighters and armies had referred to strongholds for much longer, both in Afghanistan and across much of the Islamic world. The difference was that al-Qaida would not be a mere geographical location, but an international, ideological aspiration.

The chances of fulfilling this ambition of creating a vanguard of Islamic fighters who will raise the Muslim world in a vast uprising against unbelieving local rulers and the west too remain extremely slim and the prospects for those still committed to the project unclear. Zawahiri is ailing, or maybe already dead, and no one knows who his successor might be or what he might do. But history suggests that to write off al-Qaida, even after 33 years, would be very optimistic.