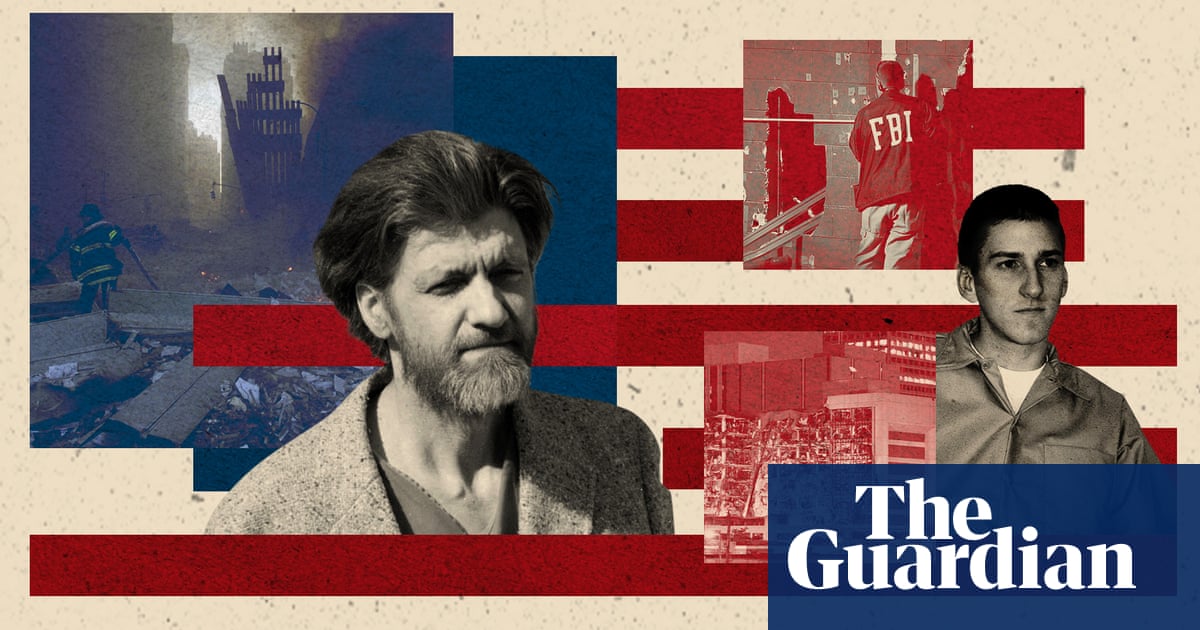

The US government acted quickly after 9/11 to prevent further attacks by Islamic extremists in the US. Billions of dollars were spent on new law enforcement departments and vast powers were granted to agencies to surveil people in the US and abroad as George W Bush announced the war on terror.

But while the FBI, CIA, police and the newly created Department of Homeland Security scoured the country and the world for radicalized Muslims, an existing threat was overlooked – white supremacist extremists already in the US, whose numbers and influence have continued to grow in the last two decades.

In 2020 far-right extremists were responsible for 16 of 17 extremist killings, in the US, according to the Anti-Defamation League, while in 2019, 41 of the 42 extremist killings were linked to the far right.

Between 2009 and 2018 the far right was responsible for 73% of extremist-related fatalities in the US, while rightwing extremists killed more people in 2018 than in any year since 1995, when a bomb planted by an anti-government extremist killed 168 people in a federal building in Oklahoma City.

Despite the statistical dominance of far-right and white supremacist killings in the US, America’s intelligence agencies have devoted far more resources to the perceived threat from Islamic terror.

“The shock of 9/11 created this incredible machinery really, in the US and globally – the creation of entire new agencies and taskforce hearings, and all those sorts of things, that created blind spots,” said Cynthia Miller-Idriss, author of Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right and a professor at American University, where she runs the school’s Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab.

“Of course, they were also interrupting plots and warning of threats. So some of that was happening, but at the same time, this other threat was increasing and rising, and they weren’t seeing it,” she added.

In the last few years alone, a gunman killed 23 people in El Paso, Texas, after allegedly posting a manifesto with white nationalist and anti-immigrant themes online. In it he wrote that he planned to carry out an attack in “response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas”.

A woman places a sign at a temporary memorial in Ponder Park honoring victims of the Walmart shooting which left 23 people dead in a racist attack targeting Latinos on 2 August 2020 in El Paso, Texas. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty Images

In February 2019, a US Coast Guard lieutenant who was a self-described “white nationalist” was arrested after he stockpiled weapons and compiled a hitlist of media and government figures. He was sentenced to 13 years in prison in 2020.

Nine black church members were murdered in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2017, by a 22-year-old who confessed to the FBI that he hoped to bring back segregation or start a race war.

But successive governments have spent most of the last two decades putting the majority of their resources towards investigating Muslims, both in the US and abroad. In 2019 the FBI said 80% of its counter-terrorism agents were focused on international terrorism, with 20% devoted to domestic terrorism.

As the government pursued Islamic terrorism, the civil rights of Muslims in America were impinged, and many innocent Muslims suffered. More than a thousand people were detained in the months following 9/11, and thousands more questioned as mosques and Muslim neighborhoods were placed under surveillance. The number of hate crimes against Muslims in the US spiked in the immediate aftermath of the attack, and have remained way above pre-2001 rates in every year since.

“There was a lack of attention from authorities – resources – but some of the actual interventions that authorities made were Islamophobic. And so they fostered some of this Islamophobia, anti-immigrant sentiment,” Miller-Idriss said.

Michael German, a former FBI special agent who specialized in domestic terrorism and covert operations, said a disparity in the attention giving to alleged Muslim actors and white supremacists was growing even before 9/11.

After that attack, however, new laws, including the Patriot Act, gave the government extra powers to surveil and target Americans, while the justice department was given more power to investigate people with no criminal record.

German, who is a fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty & National Security Program said these powers were mostly focused on Muslim Americans, while paying white supremacists little heed.

“[There was] a disparity between how the FBI targeted Muslim Americans who simply said things the government didn’t like, or were associated with people the government didn’t like, or the government suspected just because they were Muslim, and had never committed any violent crime, had never been engaged with any terrorist group versus failing to even document murders committed by white supremacists,” German said.

White supremacists march at Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. Donald Trump’s equivocal pronouncements about the far right were seen as legitimising what had once been outside of mainstream politics. Photograph: The Washington Post/Getty Images

After the World Trade Center attacks, “a tremendous amount of resources were coming into the Joint Terrorism Task Force and the counter-terrorism work”, German said. “But that was all being focused on potential terrorism committed by Muslims.”

A justice department audit in 2010 revealed that between 2005 and 2009 an average of fewer than 330 FBI agents were assigned to domestic terrorism investigation, out of a total of nearly 2,000 counter-terrorism agents.

The decision to not focus as intensely on white supremacist or domestic terrorism wasn’t just a strategic one, German said. He said the influence of money and big business had a role, as industries lobbied lawmakers and even the FBI itself to instead pursue anti-capitalist and environmental protest groups.

“The FBI needs resources. And to get resources, it needs to convince members of Congress. And Congress works most effectively when there are wealthy patrons who contribute to their campaigns,” German said.

“So the FBI has to cultivate a base of support in the wealthy community, and how can they do that? Well, by going to corporate boards, and telling them, you know, the FBI needs more resources.

“And then of course, that gets the corporate boards a lot of influence over what the FBI does. And what those corporate boards were saying wasn’t that there are minority communities in the United States that are being targeted by white supremacists, what are you doing about it?

“They were saying: ‘Hey these [anti-corporate or environmental] protesters are a real pain and you know, there’s a potential they could become violent.’”

When the government and intelligence agencies sought to expand its collection of intelligence post-9/11, that gave corporations another bargaining chip, German said – further knocking white supremacy and the far right down the priority list.

“Giant corporations hold a lot of private information about Americans, and getting access to that information became important to the FBI, so pleasing those corporations became part of the mission.”

Alongside that issue is the fact that there are “lingering racism problems within the FBI”, German said, with the agency still a predominantly white and male organization.

“So that’s one end of the spectrum, the people who are either explicitly racist or implicitly racist. Because white supremacists don’t threaten their community so they don’t see it as a threat.

“The white male agent who goes home to a white suburban community doesn’t really see a lot of white supremacist skinheads causing problems in his community. So it becomes a lesser threat.”

In 2020 there were signs that more attention was being focused on the far right. The Department of Homeland Security said white supremacists were “the most persistent and lethal threat in the homeland” as it announced a report on threats in the US.

But that came just days after Donald Trump had told the extremist group Proud Boys to “stand by” during a presidential debate.

Trump was notoriously reluctant to condemn white supremacist violence, and his “both sides” comments after the Charlottesville riots were seen as legitimizing the far right. In April 2020, as the pandemic raged in the midwest, he told his supporters to “LIBERATE MICHIGAN!” after Gretchen Whitmer, the state’s Democratic governor, imposed stay-at-home orders. Hundreds of armed rioters duly stormed the Michigan state capitol. In October 2020 the FBI charged six people with allegedly plotting to kidnap Whitmer, who had been a target of Trump’s attacks for months.

The riot in Michigan could be seen as a grim preview of the events of 6 January, when a far-right movement that had been brewing for years spilled out in Washington DC and attacked the Capitol.

Authorities investigate a pickup truck parked on the sidewalk in front of the Library of Congress in Washington last month. Photograph: Carolyn Kaster/AP

Joe Biden has been less reluctant than his predecessors to identify the danger to US citizens. In June Biden said white supremacists are the “most lethal threat” to Americans, and later that month his administration unveiled a sweeping plan to address the problem.

PW Singer, a strategist who has served as a consultant to the US military, intelligence community and FBI and is a fellow of New American, a public policy thinktank, said the growing threat of white supremacism in the US was too complex to blame just on a lack of attention from government intelligence agencies – “but it certainly didn’t help stop it”.

“Think of it as akin to a disease striking the body politic. The person was not only in active denial, deliberately avoiding the needed measures to fight it, but the normal defenses [used] against other like threats were not deployed.”

Trump may be gone, but the pandering of some Republicans to rightwing extremists seems unlikely to stop. As recently as August Mo Brooks, a Republican congressman from Alabama, defended a Trump supporter who carried out a Capitol Hill bomb threat.

“Although this terrorist’s motivation is not yet publicly known, and generally speaking, I understand citizenry anger directed at dictatorial Socialism and its threat to liberty, freedom and the very fabric of American society,” Brooks tweeted, hours after the man had parked close to the Capitol and supreme court and told police he had a bomb.

“The way to stop socialism’s march is for patriotic Americans to fight back in the 2022 and 2024 election,” he said. “Bluntly stated, America’s future is at risk.”

It’s a dangerous game, but with the rise of Trumpism and far-right extremism in conservative politics – which can be traced back to the Tea Party movement which demonized Barack Obama – it is one Republicans seem likely to continue.

“What was once the unacceptable extreme has become an accepted part of our politics and media,” Singer said.

“It is a hard truth that too many are unwilling to accept. It didn’t start on 6 January, but years before, where these extremist views were first tolerated and then celebrated as good for clicks, and then votes.”