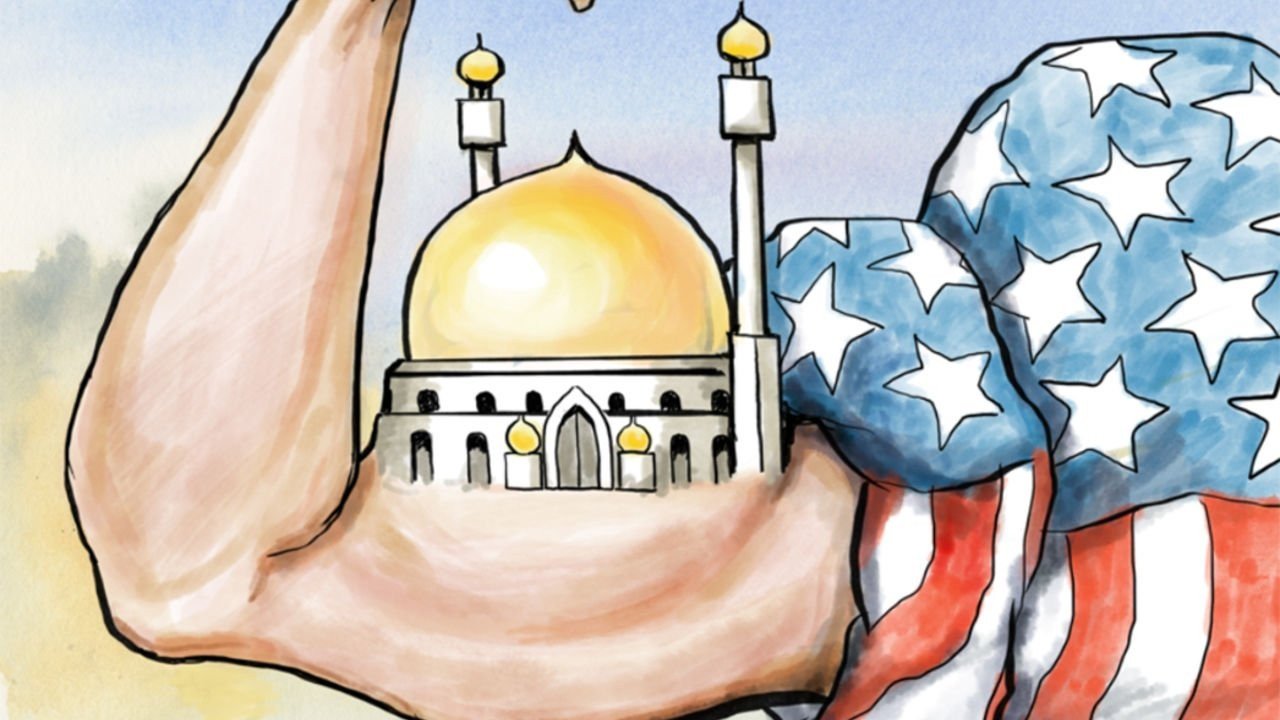

T HE PAST 20 years have mostly been golden for America’s Muslims. The community has more than doubled in size, to 3.5m. And its prominence in American life has increased exponentially.

Listen to this story Your browser does not support the

Traverse the overpasses of any big city and you will see metallic domes sparkling below. The number of mosques has also more than doubled since 2001. The minority’s secular growth is even more striking. Muslims are one of America’s most educated religious groups. More than 15% of doctors in Michigan are Muslim, though less than 3% of the state’s population is. And Muslim artists, journalists and politicians are catching up.

Mahershala Ali, Ayad Akhtar, Aziz Ansari and Hasan Minhaj are among a generation of award-winning Muslim actors, writers and comedians that has emerged in recent years. Below Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar—the first Muslim women in Congress—sit innumerable Muslim officials, elected onto school boards and into local government. Four centuries after Islam came to America, its Muslims are finding their place.

And yet the Islamophobic backlash the community suffered after the twin towers fell has increased. Half of Americans, including a large majority of Republicans, say Islam encourages violence. That is twice the number who held that view in early 2002. “Though we try to integrate, these are things we live with,” Ali Dabaja, an emergency-care doctor from Michigan, told your columnist. And then he sobbed down the phone as he recalled the time a trucker in Florida tried to run him and his two headscarf-wearing sisters (one a doctor, the other a lawyer) off the road.

Such behaviour occurs not only despite the many Muslim paragons. It is also despite America having witnessed astonishingly little jihadist violence. Islamist attacks are reckoned to have claimed 107 lives since 2001, fewer than white supremacists. And nearly half of those casualties occurred in a mass shooting in a gay club which may not have been motivated by religion. To quote Donald Trump—whose promise to bar Muslims from America was backed by 60% of Republicans—what is going on?

A familiar struggle for America, is the answer, pitting openness and dynamism against nativism and paranoia. Muslims are merely the latest minority to have been embroiled in it.

On the open side of that contest, their growth and success are testament to America’s genius for immigration. Over half of its Muslims were born abroad, including a skilled multitude enticed by the immigration act of 1965. It included the South Asian fathers of Messrs Akhtar, Ansari and Minhaj; the first two doctors, the third a chemist. Having found in America opportunity, religious freedom, civic culture and physical distance from their old lives, such Muslim migrants and their offspring tend to be more patriotic than their European counterparts and much less interested in jihad. The American dream was always an antidote to extremism.

Indeed, it is striking how many Muslims, especially younger, America-born ones, responded to the discrimination they faced after 9/11 by citing America’s promise of liberty. Mr Minhaj, whose hit Netflix show was called “Patriot Act”, describes his father’s and his own conflicting responses to the thugs who smashed their car windows; the older man fearful and resigned, the younger one astonished and incensed. Similarly, Aasim Padela, an emergency-care doctor and expert in Islamic bioethics, said the bigotry he faced even as the twin towers burned “changed my life”. A Cornell medical student at the time, he rushed to help triage the injured; but no Manhattan bus driver would open his doors to him. “My stethoscope could not conceal my beard,” he says. Defiantly he resolved to represent his Muslim values in his medical career.

Yet 9/11 does not explain the growth of anti-Muslim sentiment. George W. Bush tried hard to quell it. Muslim-bashing became nonetheless entrenched on the right mainly because of how it chimed with the broader grievance culture emerging there—especially after the election in 2008 of a black president with a Muslim name. The professed concerns of American Islamophobes underline this. They tend to worry less than their European equivalents about conservative Muslim practices and beliefs (some of which evangelical Christians share), and more about Muslim immigration. When Mr Trump launched himself into politics by suggesting Barack Obama was Muslim as well as foreign, he implied that they were synonymous. He then made Muslim-bashing central to his presidential campaign. Subsequent analysis suggested Islamophobia was his voters’ most characteristic trait. It is a form of bigotry that persists because of the grievances of a dwindling white majority, in other words. It is scarcely about Muslims—especially the reality of America’s prospering minority—at all.

That was also clear ahead of last year’s election, when Mr Trump abruptly turned his sights from Muslims to black activists. The shift was consistent with research suggesting that, for all its ugly noise, Republican Muslim-bashing may be less threatening than opinion polls suggest. Because the Muslim population is based in cities and relatively small, says Shadi Hamid of the Brookings Institution, nativists have little contact with and are unlikely to focus on Muslims for long: “We are not the main target of xenophobia because there are bigger groups to be racist about.”

Take the medicine

For another consolation, it is abundantly clear who is winning this struggle. The bigotry of the right reflects its members’ lost status. Meanwhile Muslims will continue to rise. Covid-19—or rather the madness the right has made of it—provides a powerful image of those relative positions. The anti-vaxxer Trump voters who are now likeliest to be hospitalised with the disease tend to be the most anti-Muslim Americans. The doctors treating them are quite likely to be Muslim. The irony of this is not lost on Dr Dabaja. “But when people are coping with the reality of death or the death of their loved ones,” he says, “their political agendas tend to fade.”■