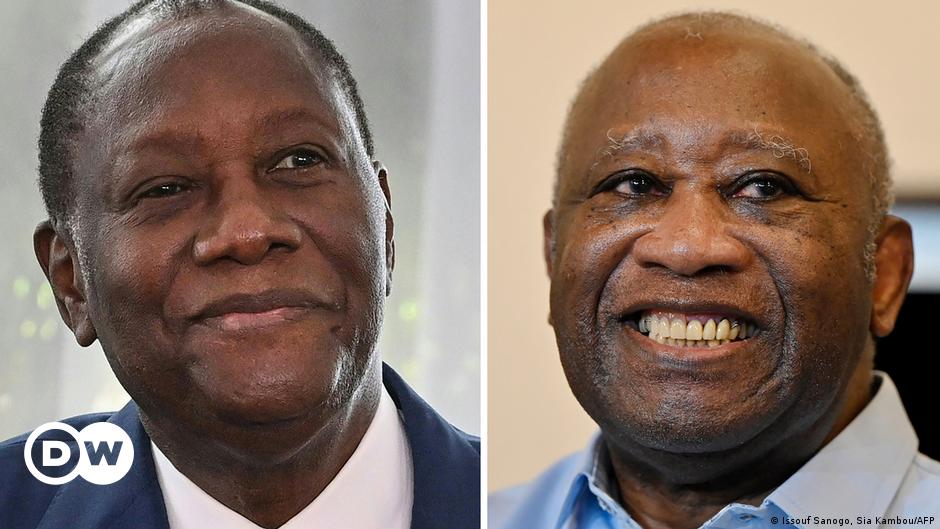

Tuesday’s meeting between Ivory Coast’s current president, Alassane Ouattara, and his rival Laurent Gbagbo, who recently returned after being acquitted of committing war crimes by the International Criminal Court (ICC), has raised tensions in the country.

But amid the uneasiness, there is also a sense of optimism among many on the streets of Abidjan, the country’s largest city.

“President Gbagbo and President Alassane [Ouattara], they are brothers. Both will show the world that there is total reconciliation in Ivory Coast,” one citizen told DW.

Reconciliation ahead of meeting

Another believes the meeting could help heal the country’s longstanding north-south divide: ”I think that the meeting between President Gbagbo and President Alassane [Ouattara] augurs good days, because for … the north and the south, there is still hope.”

Publicly, both leaders have sought to project an image of peace and reconciliation.

President Ouattara publicly welcomed Gbagbo’s recent return, using the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha to appeal for national healing.

“May the steps that have been taken for social cohesion, for reconciliation, continue to be made. May Ivory Coast continue to live in peace,” 79-year-old Ouattara said last week.

Gbagbo’s arrival on July 17 drew supporters onto the streets of Abidjan, where they were met with police

Gbagbo’s spokesperson said the two rivals have been “in touch” via phone since early July.

Tuesday’s meeting will be the first between the two since during the country’s 2010 disputed presidential election, when the Constitutional Council declared Gbagbo the winner, despite the country’s Election Commission and the United Nations recognizing Ouattara as having won the vote.

Nightmares of 2010 remain

Abroad, Ouattara was also considered Ivory Coast’s new leader with the international community, the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) imposing sanctions on Gbagbo after he refused to step down.

The ensuing political crisis triggered widespread fighting that saw some 3,000 people killed, entire villages destroyed and the hundreds of thousands displaced by the violence between pro-Gbagbo militias and Ouattara’s forces, which were supported by UN, ECOWAS and French troops and equipment.

It also widened the rift between the mainly Muslim Ouattara-supporting communities in the north and the predominantly Christian, Gbagbo-allied south.

Gbagbo was subsequently arrested in April 2011, banished from Ivory Coast and sent to The Hague to face charges of crimes against humanity brought by the International Criminal Court.

Gbagbo was hauled in front of the ICC in The Hague, and remained exiled from Ivory Coast until 2021

Gbagbo’s redemption, Ouattara’s own credibility at stake

The ICC acquitted Gbagbo in 2019, granting him permission to return to Ivory Coast.

Despite his decade-long absence, 76-year-old Gbagbo still has a large following at home — especially in the southern coastal regions, where he has a reputation for standing up for the poor and oppressed.

As for Ouattara, amid a precarious peace, in 2015 he convincingly won his second election.

But in 2020, scores of people were killed in pre-electoral clashes with the police after Ouattara controversially unveiled his bid for a third presidential term; the country’s constitution allows only two terms.

Ouattara went on to win a landslide victory in the 2020 poll but gained little credibility as the vote was boycotted by nearly the entire opposition.

The Yopougon area of Abidjan is a stronghold for Gbagbo supporters, who protested Ouattara’s third term as president

For many Ivorians, solving the differences between Ouattara and Gbagbo are key to overcoming the country’s main problems.

Although Ivory Coast has experienced vibrant economic growth since 2012, many citizens have been left behind with nearly 40% of the country’s population still living in poverty.

Ivory Coast is also floundering when it comes to creating work and education opportunities for young people between 15 and 29, who account for more than one-quarter of country’s population.

It has also failed to address its longstanding political and ethnic tensions between the north and south, according to Human Rights Watch.

Violence tore families, villages apart

One group trying to rebuild these divides is the Abidjan-based NGO Femmes de Salem.

”We know that in 2010 the Ivory Coast was on fire with very visible social fractures,” said Boussou Bintou Coulibaly, the NGO’s leader, explaining the reason for the founding of reconciliation projects bringing women together from both parts of the country.

“We had to break the ice between the women of the north and those of the south. Because through the women, for us, something could be done to bring the populations together,” Coulibaly told DW.

Anastasie Adjoua Kouadja and Cisse Makoko, who lived in a small village called Bodoukro in the Tiassale region, 120 kilometers (74 miles) from Abidjan, have benefited from Femmes de Salem’s attempts at reconciliation.

Ivory Coast has yet to reckon with crimes committed after the 2010 presidential election

Makoko’s family is originally from the north while Kouadja’s family is from the south. During the 2010 crisis, their families, who had previously lived side by side, clashed. Several houses and plantations were destroyed.

Kouadja regrets the violence that destroyed parts of her village and tore apart the community cohesion that once existed.

”We looked at each other like dogs and that’s not good,” she told DW.

But that has changed since taking part in the NGO’s project and meeting with “our sisters from the north,” including Makoko, she said.

“Our meeting went very well, we took pictures of each other and exchanged phone numbers,” Kouadja said.

“We are one people despite ethnic, religious and even political differences. Reconciliation came very naturally among us,” said Makoko. “We have to live together so that the country can move forward.”

Many hope that today’s meeting between President Alassane Ouattara and Laurent Gbagbo will have a similar outcome.