Mila’s anti-Islam rant on Instagram drew thousands of hate messages and resulted in a landmark cyberbullying case.

Paris, France – It all started with an Instagram broadcast on January 18 last year.

Mila, then 16, with a head of newly dyed purple hair, went on a rant against Islam, addressing some of her 10,000 followers who tuned in.

“The Quran is a religion of hatred. There is only hatred in it. Islam is s**t, your religion is s**t,” she said in her video, using crude imagery to refer to “your God.”

In the following weeks, as she defended her stance, she received about 100,000 hateful messages.

Soon, her legal case caught national attention and tested France’s new cyberbullying laws.

Last month, a French court convicted 11 people for harassing Mila online.

The case reignited a national debate about free speech, including the right to use blasphemy against religions, which is protected by French law.

Highly politicised in France, the justice system, police, mainstream media outlets, and major politicians all became involved in the Mila affair, as it has become known.

‘I said what I thought’

On February 3, weeks after her broadcast, Mila told French media how the situation escalated.

She told a TV audience that she was a lesbian. When asked who she finds attractive, she replied that “Blacks and Arabs” were not her type.

Then, the conversation switched to Islam.

“I am not a racist, not at all. You can’t be racist about a religion,” she said on Le Quotidien. “I said what I thought, I am completely in my rights. I don’t regret it at all.”

Mila, centre, was forced to change schools and accept police protection due to threats to her life in the wake of her first videos being put online in 2020 [Bertrand Guay/AFP]

After that appearance, she received tens of thousands of hate messages, including death and rape threats, across Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat.

She was urgently taken out of school, as its address was shared and her security deemed at risk.

Mila filed a lawsuit for the death threats, with Richard Malka as her lawyer. No stranger to big cases, Malka has represented the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo since the 1990s.

French politicians chimed in, defending free speech.

In a tweet, the far-right leader Marine Le Pen said, “The words of this young girl are the oral description of Charlie’s cartoons, nothing more and nothing less. We can find it vulgar, but we can’t accept that, for this, some people condemn her to death, in France, in the 21st century.”

President Emmanuel Macron told the newspaper Le Dauphiné Libéré that the law was clear. “We have the right to blaspheme, to criticise and to caricature religions.”

He added, “In this debate, we have lost sight of the fact that Mila is an adolescent. We owe her protection at school, in her daily life, and in her movements.”

Guilty verdicts

Months passed as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold.

But in November 2020, Mila posted another video, this time graphically insulting “your buddy Allah” on TikTok.

She received death threats again, with one user threatening to behead her, and Mila was definitively switched to home-schooling.

The 13 people found guilty of harassing her were aged between 18 and 29; 11 were handed suspended prison sentences of between four and six months.

The French court used the 2018 Schiappa Law against cyberbullying and digital raids, created by citizenship minister Marlène Schiappa, to carry out the sentences.

“I have supported young Mila and her family since the beginning of this case. My wish is to protect all people who are threatened by violence,” Schiappa said.

For Mila’s supporters, the verdict signified hope for cyberbullying victims.

Justine Atlan, general director of Association e-Enfance, a non-profit that has a national helpline for victims of online abuse, told Al Jazeera that the verdict was “very proportional to the authors” and “quite coherent”.

“She found herself the victim of a digital raid of the kind that adult public figures can have,” said Atlan, whose organisation worked with Mila to collect the hate messages and relay them to the police.

A recent report by Association e-Enfance revealed that one in 10 teenagers in France claimed to have been a victim of online violence, 59 percent of whom are young girls, between 10 and 19.

Atlan said she hoped the verdict would be “a lesson” and that people would be held accountable for what happens online.

“Fortunately, these cases are exceptional, but they should be used to show how far these incidents can go,” she said.

But the case and its result have proved just as divisive as Mila’s provocative video.

Juan Branco, the lawyer of Jordan, one of the 11 people convicted, said the trial was organised “as a show in a very disturbing way for me”.

The lawyer, known in France for defending many “gilets jaunes” (yellow vest) protesters in court and acting as Julian Assange’s legal adviser in 2015, took up the case when Jordan contacted him on Twitter, seeking legal aid.

Branco told Al Jazeera, “When you try to create symbols through justice, in general, it is against the rights of individuals who are judged, but also potentially against the victims themselves.

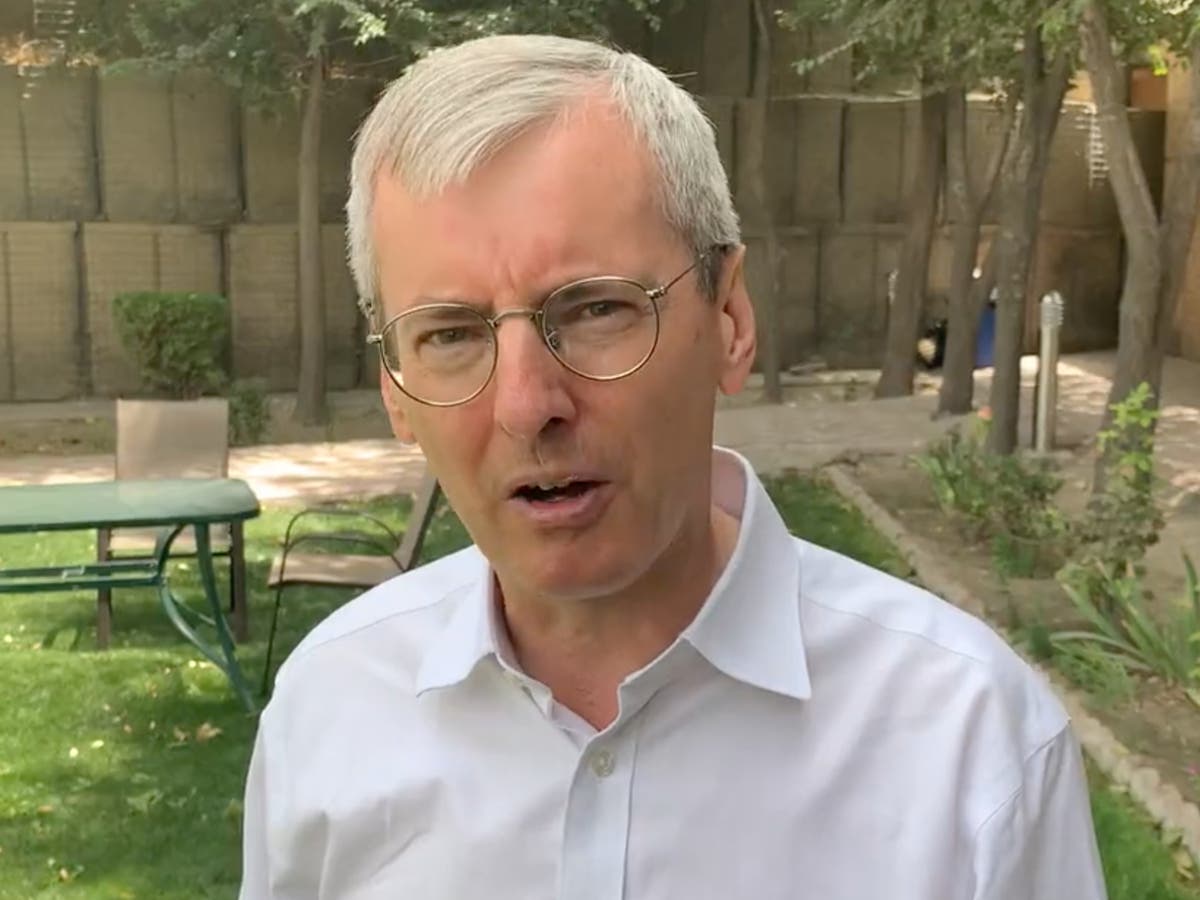

Branco, pictured, said July’s trial was ‘organised as a show’ and ‘instrumentalised’ by France’s mainstream media at the cost of the defendants [File: Bertrand Guay/AFP]

“I take cases in general in which you have normal citizens, or weak persons, that are attacked by a part of the system. Unfortunately, the Mila case became that.”

He said that French mainstream media “instrumentalised” the trial to create “a new Joan of Arc” symbol out of Mila.

Mila gave regular interviews on talk shows where she was portrayed as a victim, yet no space was given to those who felt offended by her anti-Islam posts, according to Branco.

The right to blaspheme

On June 23, Mila released a widely publicised book titled,“I am the price of your liberty.”

On July 8, a day after the verdict, she visited the Great Mosque of Paris, posing for photos for media outlets next to the rector, Chems-Eddine Hafiz, with a copy of the Quran in her hand.

Branco’s client, Jordan, was the oldest defendant at 29.

Raised as a Catholic, he has no criminal background.

On Twitter, where he has about 50 followers, he shared his reaction to an explicit post that Mila wrote about Allah (God).

Branco said his client acknowledged his tweet was “vulgar” but that it represented no serious threat.

“There was no fundamentalist or wannabe terrorist that was prosecuted,” Branco said.

As the first significant case to use the Schiappa Law, Branco said the 13 defendants were chosen as “scapegoats” and that the trial was “clearly meant to send a message to the world, and especially to the French population”.

“A society that does not respect belief and religion is in real danger,” Branco said. “That’s when “laïcité (secularism)” becomes spiteful.”

Imen Neffati, an historian on race, Islam and press freedom in France, said that while the right to criticise religions should be respected, this principle is often used to cover up Islamophobia.

“Criticism of Islam – especially in France – is often undertaken in a racist manner which demonises Muslims, or at the very least draws on and perpetuates racist tropes,” Neffati told Al Jazeera.

The Mila affair is not the first time a trial in France has set off a debate about the right to blaspheme.

In 2007, Charlie Hebdo was sued by the Great Mosque of Paris for publishing cartoons deemed offensive, including one of the Prophet Muhammad with a bomb in his headscarf.

Then, Malka, Mila’s lawyer, successfully defended Charlie Hebdo.

“The unfolding of the Mila story is predictable,” Neffati said. “What was interesting to see, is Richard Malka being her lawyer.”

Malka declined to comment to Al Jazeera, but Neffati, who has followed his work for years, said that he is dedicated to defending the right to free speech in courtrooms.

“He himself admitted that, like Charlie Hebdo’s trial, Mila’s is also symbolic.”

The verdict was seen as a victory to those who champion “laïcité” and free speech.

Yet, against the backdrop of the recently introduced “separatism bill“, which critics have claimed further discriminates against Muslims in France, there are concerns that the Mila affair is a reminder of the tension towards Muslims in France.

In the country that hosts the most Muslims in Europe, Neffati said that big media events – such as Mila visiting the Great Mosque – show that representatives of Islam are under pressure “to constantly explain and justify that Islam is not a violent religion, or incompatible with French values”.