In 2000, the race equality thinktank the Runnymede Trust published a report about the “future of multi-ethnic Britain”. Launched by the Labour home secretary Jack Straw, it proposed ways to counter racial discrimination and rethink British identity. The report was nuanced and scholarly, the result of two years’ deliberation. It was honest about Britain’s racial inequalities and the legacy of empire, but also offered hope. It made the case for formally declaring the UK a multicultural society.

The newspapers tore it to pieces. The Daily Telegraph ran a front-page article: “Straw wants to rewrite our history: ‘British’ is a racist word, says report.” The Sun and the Daily Mail joined in. The line was clear – a clique of leftwing academics, in cahoots with the government, wanted to make ordinary people feel ashamed of their country. In the Telegraph, Boris Johnson, then editor of the Spectator magazine, wrote that the report represented “a war over culture, which our side could lose”. Spooked by the intensity of the reaction, Straw distanced himself from any further debate about Britishness, recommending in his speech at the report’s launch that the left swallow some patriotic tonic.

The Parekh report, as it was known – its chair was the political theorist Lord Bhikhu Parekh – was not a radical document. It was studiously considerate. Contrary to the Telegraph front page, it didn’t claim “British” was a racist word. It said that “Britishness, as much as Englishness, has … largely unspoken, racial connotations”. This was the sentence that launched a thousand tirades, but where did this idea come from? Follow the footnote in the offending paragraph and you arrive at the work of an academic called Paul Gilroy.

Gilroy watched this “depressing and deeply symptomatic” episode unfold from across the Atlantic. He had joined Yale University the previous year, having left Britain in search of greener pastures. Several other non-white British academics had done the same: an article in the Guardian from 2000 about this exodus – headlined “Gifted, black … and gone” – quotes one of Gilroy’s reasons for leaving: “Even to be interested in race, let alone to assert its centrality to British nationalism, is to sacrifice the right to be taken seriously.” The response to the Parekh report seemed to confirm that he had made the right decision. Twenty years later, it can feel like little has changed. Time moves forward but, on this issue, Britain stays still, having the same arguments over and over.

Get the Guardian’s award-winning long reads sent direct to you every Saturday morning

Gilroy, 65, has since returned to Britain. Today, he is widely regarded as the country’s pre-eminent scholar of race, culture and nationalism. It’s a status that he has acquired slowly, without fanfare, through a steady drip of books, essays and lectures rather than dramatic public interventions. Over four decades his work has spanned disciplines – literature, history, philosophy, music, sociology – but it is built around a simple plea: that race and racism be taken seriously.

He first made a name for himself in the late 1980s with his book There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack, which argued that racism was “deeply interwoven” with nationalism in Britain. His 1993 follow-up, The Black Atlantic, still his most influential work, used the writings of enslaved people and their descendants to demonstrate their centrality to the making of the modern world. In 2004’s After Empire, more than a decade before the referendum on EU membership, he diagnosed Britain with “postcolonial melancholia”: an inability to mourn the loss of imperial greatness, which was encouraging a corrosive nationalism.

Gilroy is a worldly scholar, who wants us to look beyond the nation-state and think on a planetary scale. He has been working for several years on a book about the effects that the climate crisis is having on our ideas about race and humanity. But he can’t quite get Britain – or England, really – off his mind. In our conversations over recent months, he circled around the virulent nationalism that accompanied the UK’s exit from the EU, the inhumanity of the Home Office’s policy toward migrants, and the renewal of the far-right political forces that he encountered as a young person in postwar London, when he, like so many others, was intimidated by racists in the street. “I really tried to warn people about racism and nationalism in this country,” he told me, toward the end of one interview, when Brexit came up. “To have all of those things that could be seen so clearly swell up into this Leviathan and beat everything that I think is important and beautiful and serious and democratic about this culture to death … It has given me one or two things to think about.”

In this moment of resurgent anti-racist politics, people are turning to Gilroy’s work. An activist told me that she saw a placard listing the names of essential thinkers at a Rhodes Must Fall demonstration in Oxford – and Gilroy was the only living person on it. When the Formula One driver Lewis Hamilton shared a #BlackLivesMatter reading list on social media, he included There Ain’t No Black …, alongside works by Malcolm X and Maya Angelou. Steve McQueen’s acclaimed TV series about Caribbean life in Britain, Small Axe, is further evidence of his influence: Gilroy was credited as an adviser. “He’s the foremost intellectual in the United Kingdom: not an if, not a but, not a maybe,” McQueen, a friend of Gilroy’s, told me over the phone.

He may not have the public profile of someone like the late Stuart Hall, who co-supervised his PhD, but Gilroy’s reputation in the field is unrivalled. People who work on race speak of his deep, formative influence; concepts that he developed such as the “black Atlantic” – which refers to the transnational slave-descended cultures that span Africa, Europe and the Americas – are firmly embedded in academia. In 2019, he was awarded the Holberg prize, a $700,000 award funded by the Norwegian government that is often called the Nobel prize of the humanities. (Not a single British newspaper covered it.) The awarding committee described him as “one of the most challenging and inventive figures in contemporary scholarship”.

Too challenging, perhaps. For all the plaudits, there is something unsettling about Gilroy’s way of looking at the world. He is an untimely figure. His ideas don’t correspond to the vogueish pieties of identity politics or even cutting-edge studies of race. He is that most intellectually unfashionable thing, a humanist. And despite his insistence on understanding the importance of race, he has paradoxically spent much of his life encouraging people to work towards something radical, even utopian: moving beyond the idea of race altogether.

Gilroy does not like the spotlight. He was hesitant about being the subject of a profile, and friends of his seemed surprised when I told them that he had eventually agreed. There were moments in our conversations when he would artfully direct me away from personal questions or reflect wincingly on something he’d once said. He seemed wary of what happens to a life when it is turned into a narrative, the way it can be smoothed into something neat, familiar and false. In his work, he has always condemned the tendency to reduce the world to comfortingly simple categories.

When we first met in person, in between pandemic lockdowns last winter in Finsbury Park, north London, Gilroy was easy to spot between the dog-walkers and morning joggers. He is short and bearish, and has a crown of dreadlocks, wisped with grey, reaching down to his waist. Dressed in black, wearing mud-stained walking boots – a partisan Londoner, he is also an outdoors person – he moved across the sodden grass with careful, almost monkish purpose. In conversation, he speaks fluently, gently, like a late-night DJ soothing listeners as they drive, but his tone belies a barbed impatience with the state of things. “I can’t watch videos of murder,” he said in a recent discussion with the historian David Olusoga, referring to the killing of George Floyd. “I’m already angry enough.” Racism, nationalism, intellectual complacency: these disfigure the world and move him, and this hasn’t waned as he’s grown older.

His mother, Beryl Gilroy, was a teacher, psychotherapist and novelist. She migrated from what was then British Guiana in the Caribbean in 1952, but she wasn’t an immigrant: like the rest of the Windrush generation, she was a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies, moving from one part of the empire to another. If that cohort was expecting a measure of hospitality, they found a hostile environment. “Unable to adjust to the presence of semi-strangers who, disarmingly, knew British culture intimately as a result of their colonial education, and who represented a vanished pre-eminence,” her son would later write, “the country developed a melancholic attachment to its lost imperial past.”

Facebook Twitter Graffiti in support of Enoch Powell in 1968. Photograph: Evening Standard/Getty Images

This was the era of the colour bar, when those newly arrived discovered the hollowness of their formal rights. Landlords would refuse to rent rooms based on what the neighbours might think. The graffiti – “Keep Britain White”, “[Enoch] Powell for PM” – put things more plainly. So, too did the violence: from the police, the marauding teddy boys, and the assailants, never caught, behind the murder of the Antiguan carpenter Kelso Cochrane in 1959.

In her 1976 memoir Black Teacher, Beryl Gilroy described what it was like to navigate the education system of postwar London. She encountered parents who didn’t want a black woman teaching their children, and had to deal with racism from the pupils themselves, who were often parroting their parents. Life among the “workaday English” often amounted to a “daily struggle for survival and dignity”, but she was unflappable, eventually becoming the headteacher at Beckford primary school in north London.

In one scene of the memoir, though, we see her stalked by self-doubt. She worries about the child she is carrying, who was the product of what was once called “miscegenation”, the mixing of races. Her husband, Pat Gilroy – a trained chemist and a communist, who left the party after Moscow’s tanks rolled into Hungary in 1956 – was white. “Might there not be some flaws in the chromosomes?” she wonders, against her better instincts. “After I had defeated an army of nightmares my fears subsided, but I remember to this day the anxiety with which I first examined my son, seeking some flaw, born of a fear buried deep down inside me.”

With a white father and a black mother, Paul – named after Paul Dienes, a Hungarian intellectual and friend of his father’s – knew early on that he was different, and that sameness was overrated. Gilroy is not forthcoming about his childhood. He resisted the story that seemed to be taking shape as I asked him about it: the scholar of race who was drawn to the subject because of the racism he experienced as a child. “I am so phobic about the cult of victim-speak that I don’t want to narrate my life in that way,” he told me.

Those formative moments can’t be erased, either. In the introduction to his book Between Camps, he recalls a childhood memory of coming across the painted insignia of the British Union of Fascists, Oswald Moseley’s political party, on a wall in bombed-out London. What was this doing in a country that had only recently helped defeat nazism? “I think that was a stimulus to begin a kind of critical reflection on the power of racism and fascism and nationalism in British life,” he said. “It was literally having my face rubbed in all that shit.”

As a teenager, Gilroy was drawn to the affirmative politics of black power, grew out an afro, and immersed himself in soul and funk. “We people, who are darker than blue,” Curtis Mayfield, sang at Finsbury Park’s Rainbow theatre in 1972, with a teenage Gilroy in attendance. “Are we gonna stand around this town / And let what others say come true?”

His mother didn’t always make him to go to school because she knew the kind of things teachers said about kids like him. Instead, he would read voraciously, often at the local library in North Finchley. Through his mother, he discovered books – such as The Souls of Black Folk by the African American polymath WEB Du Bois – that he would wrestle with for the rest of his life.

Gilroy failed his English O-level exam, having gone out the night before to see the American singer-songwriter Boz Scaggs play at the Roundhouse in Camden. But he ended up at Sussex University, where, browsing the university bookshop one day, he came across a collection of essays, Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain. “I thumbed through it and thought, wow,” he told me. Until then, he hadn’t realised that scholars wrote about things like football, or pop music, or Caribbean culture. Now, after this encounter, academia seemed bigger, closer to life itself. Maybe, he thought, there might be a place for him.

The book that had captured Gilroy’s imagination came from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham, one of the few institutions producing academic work that made sense of what Britain looked like from ground-level. The CCCS was under the directorship of Stuart Hall, the pioneering Jamaican intellectual who famously coined the term Thatcherism and transformed British leftwing thought by focusing on the importance of culture.

When Gilroy joined the centre as a postgraduate student in 1978, he found that it had an egalitarian ethos; the traditional hierarchy dividing students from teachers was undermined. In 1982, he and a number of his fellow students published a text, The Empire Strikes Back, a landmark in the field of British cultural studies. Its central theme, developing Hall’s work, was that the hard-right nationalism of the emergent 80s was being secured through appeals to racist fears.

The 80s were a heady decade, in which battles over belonging were constantly being fought. While the far right whipped up support by promising to “repatriate” them, Gilroy’s generation affirmed that they were “here to stay and here to fight”, as one leftwing group put it. His was a cohort, actually born in Britain, that was “equipped with a sense of entitlement that their parents had not been able to enjoy”, as Gilroy later wrote. They were called the rebel generation for a reason: the 1981 riots, in places like Brixton and Toxteth, were a revolt against police harassment, and it was thanks to them that Gilroy found employment after leaving Birmingham. “Suddenly there were jobs in local government in new areas around policing, equal opportunities, around women’s needs and experiences,” he said. He worked at the Greater London Council (GLC), the city authority under the radical-left leadership of Ken Livingstone, where Gilroy did research for a unit that monitored the Metropolitan police.

He also gigged as a freelance journalist, writing for the counter-cultural music press. He got into prickly debates about jazz in the pages of the Wire and interviewed James Baldwin for City Limits. (“I never got on with the English in general,” Baldwin told him, “People who believe that an elderly British matron is the Empress of the Indies and Queen of all Africa are dangerously removed from reality.”) He was finding it hard to enter academia. “I wasn’t perceived as somebody who was staying within the bounds of the acceptable limits of scholarly research. A lot of the hostility came from people on the so-called left,” he said.

Facebook Twitter A soundsystem in west London in 1983. Photograph: Peter Anderson/Pymca/Rex/Shutterstock

His first book, There Ain’t No Black … , published in 1987, was like a little grenade thrown into the discourse. His targets included English Marxists who couldn’t understand the importance of thinking carefully about race; sociologists who portrayed Britain’s black population as either victims or criminals; the “new racism” of Thatcher’s Britain; and even the GLC, his old employer. In the book, Gilroy took riots and social movements to be as politically significant as any political party or trade union. “My brain kind of cracked open when I read it,” Ruth Wilson Gilmore, the celebrated American theorist of prison abolition, told me.

It is the second chapter that furnished the ideas that would, during the Parekh affair, offend the rightwing press. Gilroy marshalled a long list of examples – pervasive phrases such as “the island race” and “bulldog breed”; the way politicians spoke about immigrants as aliens; laws that privileged immigrants with a grandparent born in the British Isles – to argue that race and nation were enmeshed in the British psyche. The government’s obsession with repatriating “illegal immigrants” was further evidence. Deportation, he wrote acidly, “assists in the process of making Britain great again”.

Most powerfully, Gilroy treated Britain’s Caribbean settlers not as a problem to be solved, but as people whose culture offered sophisticated readings of the world. He saw the soundsystem culture of reggae and dub – whose body-shaking bass frequencies could be heard, and felt, in parties across London – as harbouring a radical critique of the modern world. Darkened dance halls transported revellers out of the oppressive present, while the music’s lyrics punctured the drudgery of labouring under capitalism.

Caribbean culture was also re-colouring Englishness itself. Gilroy analysed the 1984 single Cockney Translation by the London-born reggae artist Smiley Culture, which playfully juxtaposes cockney rhyming slang and black patois. “The implicit joke beneath the surface of the record,” he wrote, “was that though many of London’s working-class blacks were cockney by birth and experience … their ‘race’ denied them access to [that] social category.” He saw the song as a sign of his generation’s emergent, hybrid Britishness.

Music is central to Gilroy’s work, providing a kind of sonic argument against narrow nationalism. In his view, the history of black music is a powerful demonstration of how cultures, races, identities are all mongrel things, which can’t be neatly packaged into ethnic parcels. Even a genre as seemingly American as hip-hop isn’t purely American, he has pointed out: it was fertilised in the Bronx by Caribbean sound systems.

It was after a conversation with a musician, David Hinds, of the reggae band Steel Pulse, that Gilroy grew the dreadlocks that he keeps to this day. Interviewing him for a music zine during his Birmingham days, Gilroy spoke with Hinds late into the night, debating black power and music, and discussing Rastafarianism, a socio-political religion that connected people across the black Atlantic world. Growing out dreadlocks was a way of signifying one’s ethical commitment to the “sufferers” of the world. In the Britain of the 70s and 80s, it was also a dangerous way to stand out.

When I asked him about this, more than four decades later, Gilroy resisted divulging what in particular prompted the decision to grow dreadlocks. I could tell that I was encroaching on personal territory. Instead, he answered by way of analogy. He talked about George Orwell, a figure whom he admires in all his contradictory complexity. In his essay A Hanging, set in Burma where he was a colonial officer, Orwell describes accompanying a colonial subject to the gallows. During this short journey, a dog runs up to the condemned and tries to lick his face. Moments like these humanise the prisoner, which horrifies Orwell, as it makes the injustice of what is happening inescapable.

In Burma, Orwell decided to tattoo his hands. “He did this to make sure he would never be comfortable in polite society,” Gilroy said. “He marked his body in a way that said to them: I am not one of you.”

An hour after sunrise, on a bright, cloudless day earlier this year, I met Gilroy on Hampstead Heath in north London for a walk. “There are so many migratory birds arriving at the moment it’s a joy,” he had written in an email a few days earlier. He was once again dressed in black, this time with a pair of binoculars around his neck and with dark-tinted, circular sunglasses. He lent me a pair of “bins”, as he called them, and we walked over the hills and through the ancient woodland. “If we’re really lucky,” he said. “We’ll see a kestrel.” (I had heard from his friends that Gilroy was a birdwatcher, but when I first put this to him, he flinched. “I don’t like ‘birdwatcher’ as an identity category,” he said. He stressed that he does not wear camouflage or go to bird fairs and that he’s “not part of that culture”.)

The green, sun-speckled heath was almost empty of people. The morning air was piped with birdsong. It was a pastoral scene, the kind that might be called typically English. As we walked, Gilroy identified varieties of bluebell and rhapsodised over ancient oak trees. He has an exacting ear, easily distinguishing different species of bird from their interlaced song. “A lot of these birds have migrated from west and central Africa,” Gilroy said. “What can I hear right now? I can hear a great tit, a blue tit, and there’s a particular kind of warbler – that sound – which comes up from the area between Niger and Senegal.” Later, to a bemused university colleague who happened to be walking by, he taxonomised three types of woodpecker.

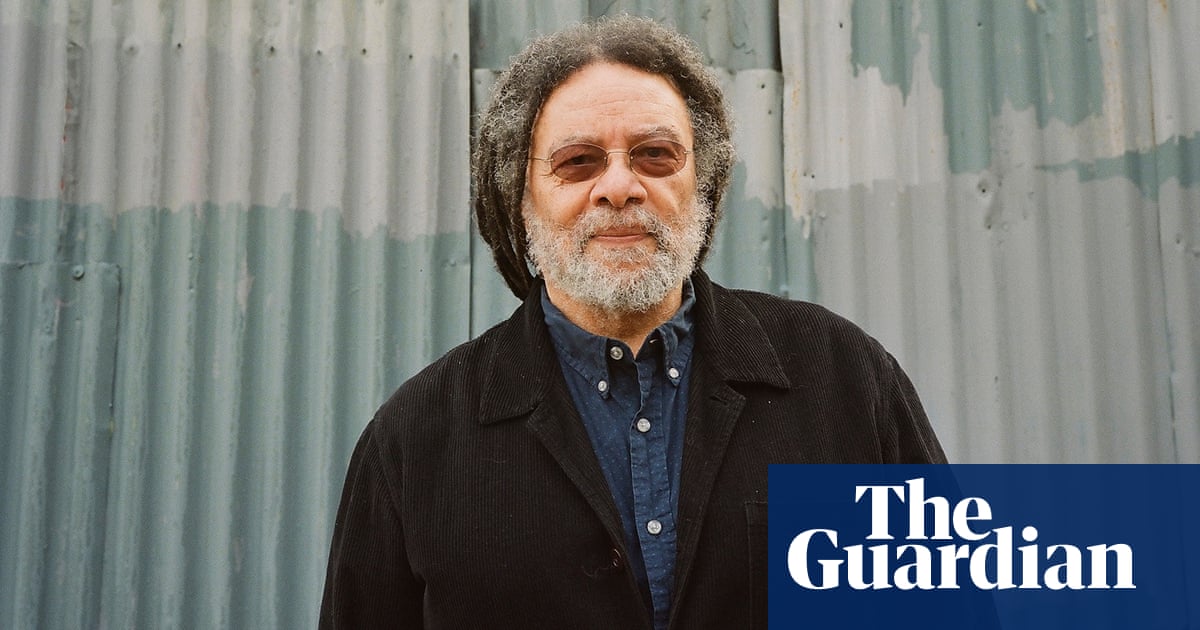

Facebook Twitter Prof Paul Gilroy near his home in north London. Photograph: Eddie Otchere/The Guardian

The day before, Gilroy had delivered his inaugural lecture at UCL, where he has been a professor since 2019, via videolink. He used it to make sense of Boris Johnson’s government and the Sewell report, published in March by the government’s centre for race and ethnic disparities. For Gilroy, the report – which clumsily downplayed the significance of racism in British life – signalled an attempt to wind back the political clock to a time when anger at racism could be dismissed as people being chippy. “It’s designed to be an insult to the likes of me,” he told me as we walked.

The culture wars have been simmering for as long as Gilroy has been alive. In the 80s, he wrote about how the press would claim Labour-run councils’ anti-racist endeavours were destroying freedom of speech. But much has changed, too; the Conservative cabinet, for instance, is more diverse than ever before. “Overtly racist messaging on immigration, culture and heritage,” he said in the lecture, “while sock-puppeting the diversity and inclusion of minority government affiliates has, so far at least, proved to be a way to hold a new electoral bloc together and maintain the high temperature of populist and authoritarian ultra-nationalism.”

But Gilroy believes there’s something brittle about the Conservatives’ approach, which seeks to launch American-inspired battles over cultural values. “I think that the British political class has been entirely bereft of any ideas of its own for a very long time,” he told me. “And its dismal inability to imagine a future for this country that is not an American future is expressed in the turn towards denouncing ‘critical race theory’ or going on about these things.”

Race and racism have never been, for him, about individual attitudes. They rather constitute a terrain on which politics takes place, where social meaning is made. In After Empire, he describes race as something that “absorbs the cries of those who suffer by making them sound less human”. The triumphant indifference of the UK government towards the suffering of others – it is in the process of making it even harder for refugees to claim asylum – is a sign that race continues to do its pernicious work.

The anti-racist mobilisations of 2020, the largest in British history, sparked by the murder of George Floyd in the US, took Gilroy aback. He remembers watching the toppling of the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston on a livestream. For many years, he had felt unsure about whether such statues should fall. He preferred to see them transformed, as in Hew Locke’s 2006 artwork Restoration, which imagined the statue of Colston smothered in layers of guilty gold, or the May Day protesters who once gave Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square a grass Mohican and lick of red paint. Gilroy is not an instinctive iconoclast: as a child, he told me, he queued with his parents outside Westminster Hall to see Churchill’s body lying in state. He believes that politeness and civility are undervalued virtues.

But his doubts were swept away by Bristol’s colourful crowd. “I couldn’t believe it,” he told me. When we spoke in December, he still seemed euphoric at the memory. Seeing Colston sink into the water had felt like a “beautiful symbolic eruption”, a glimpse of what England could be. As the months went by, some of that optimism waned. “We witnessed something special and incredible last summer,” he told me on Hampstead Heath in spring. “But I’m not seeing a lot of continued momentum. Maybe I’m not looking in the right places.” Gilroy is at his gloomiest when thinking about the effect that “timeline media” like Twitter and Facebook is having on young activists, drawing them into circular and parochial arguments online.

Facebook Twitter The statue of Edward Colston being pushed into the River Avon in Bristol in June 2020. Photograph: NurPhoto/Getty Images

Anti-racism has changed since Gilroy’s youth, its edge blunted. For much of the 20th century, being against racism meant being for a radically different political and economic settlement, such as socialism or communism. Today it can mean little more than doing what Gilroy mockingly calls “McKinsey multiculturalism”: keeping unjust societies as they are, except with a few “black and brown bodies” in the corporate boardrooms. (“I’m not very interested in decolonising the 1%”, he told me.) What is left is a more individualistic anti-racist culture, which is keen on checking privilege and affirming the validity of other people’s experiences, but has trouble creating durable institutions or political programmes.

There are moments when Gilroy shifts into lyrical lament, but he usually catches himself and tries to correct course. He has described himself as a “cosmic pessimist” moved by the “obligation to find hope”. During one conversation, when I asked whether figures like Priti Patel, the UK government’s hard-right home secretary, whose parents were Indian migrants from east Africa, represent the end of a unifying anti-racism, Gilroy demurred. “For every Priti Patel, for every ‘Dishy Rishi’, there are people out there doing things that are important work in solidarity with one another,” he said.

He talked about the annual march to Downing Street that memorialises the hundreds of people who’ve lost their lives to police violence. You can see “all kinds of faces” on those walks, he said. (He tries to attend each year.) Then he described the aftermath of the Grenfell fire in 2017, when people of all religions responded with food, support, solidarity. The rhetoric that came from the survivors of the Grenfell fire stirred him. “It was strongly humanistic actually,” he said. Their banners, he explained, critiqued the murderous crime that they had suffered in the language of a common humanity.

A few years ago, on board a train headed for New Haven, Connecticut, Gilroy noticed something on the other side of the window: a bald eagle perched in a tree. He turned to his fellow commuters to see if they were also interested in what was, after all, their national emblem. They weren’t. “They just thought I was some crazy black person,” he recalled. By this point in career, in the early 2000s, Gilroy had left the UK for Yale, where he would become chair of the African American Studies department. He is proud of what he accomplished there, but there was some homesickness – and controversy.

One of the guiding principles of his work is a hostility towards “ethnic absolutism”, be it white supremacism or black nationalism, which, Gilroy has said, “can be as toxic as any other form of nationalism”. (He has pointed out that the black nationalist Marcus Garvey once boasted that his organisation was among the “first fascists”.) Above all, he is deeply sceptical about the very idea of race itself. He sometimes places the word “race” in scare quotes to remind his readers that racial categories like black and white do not refer to some essential truth that stretches back through time. Instead, they are a modern invention, dating back to the ordering of the world by European imperialism. He likes to direct attention to the artificiality of these categories, the way they are made and remade. Indians during the 1857 rebellion against British rule were called “niggers” by officials; West Indian people, like Gilroy’s mother, only became “black” when they arrived in England. (“How I hated that word ‘black’ and the emotions, concepts and associations it aroused,” Beryl Gilroy wrote in her memoir.) As her son once put it, “It’s white supremacy that made us black.”

This rejection of race doesn’t entail the denial of racism. Quite the opposite: race is a fiction with real effects – and Gilroy has spent much of his life pointing these out. But its constructed nature does mean that when we see a person’s racial identity, what we’re really seeing is a “virtual reality given meaning only by the fact that racism endures”, as he has written. Subjugated people might find solace and community in their race, but the long-term consequence of anti-racist work should be to discard the idea of “race” altogether.

Gilroy spent the 90s weaving these ideas into his third major book, Between Camps – or as it was more provocatively titled in the US, Against Race – which came out when he was at Yale. The book develops a complex argument about the lingering afterlife of fascism in capitalist democracies, which is connected to a provocative critique of identity politics. Race, he argued, was becoming antiquated – and this was a good thing. “Action against racial hierarchies,” he wrote, in what is perhaps his most quoted line, “can proceed more effectively when it has been purged of any lingering respect for the idea of ‘race’.” Between Camps was also deeply critical of a regressive “conservatism” in corporate black American culture, which trafficked in a commodified blackness. (Among his targets were Spike Lee’s decision to set up an advertising agency, and the nihilism of much contemporary hip-hop.)

Hazel Carby, who has been friends with Gilroy since their days at Birmingham, was head of Yale’s African American studies department at the time. As a reporter wrote in 2001, she was hoping that Gilroy’s arrival at Yale would help broaden “the field’s purview beyond the borders of single nations and single-minded conceptions of race”. It did, but he didn’t endear himself. “The audience bristled at this limey’s apostasies” is how the cultural critic Sukhdev Sandhu described one of Gilroy’s public appearances during this time. Some American critics found Gilroy’s arguments muddled, haughty or excessively broad. Others felt that he had overlooked the practical implications of rejecting race: would it mean the end of anti-discrimination laws, for instance? Prof Ruth Wilson Gilmore loved Between Camps, but it didn’t go over well with all her students. “I found that [some of them] found it really nerve-racking and distasteful to think that race as a category should go away,” she told me. “And that there was something wrong with somebody who thought that way.”

When I asked him about his experiences in the US, Gilroy was hesitant. It was clear he was wounded by the period. “I don’t want to make this into an argument with black Americans because I’ve been immensely affected by that history and culture, and it’s educated me in ways that I’m really grateful for,” he said. Much of his work, particularly his early books, had resonated there too. Saidya Hartman, a celebrated professor at Columbia University, told me about the formative impact of The Black Atlantic on her work. “At that moment, in US scholarship, the emphasis was still on minimising the role of the Atlantic slave trade and slavery in the making of capitalism,” she said. “So to have the Black Atlantic argue so powerfully for its constitutive role in the making of modernity was really important.”

But Gilroy admitted to me that he struggled with what he called the “parochial” elements in African American studies. Eventually, he said, he experienced such “unpleasantness at the hands of some African American intellectuals who objected to my expressing my opinions about them as an outsider” that he returned to the UK. For some thinkers in the US, this irritation persists. In his 2017 book Black and Blur, the theorist Fred Moten wrote a lengthy and unsparing footnote that took Gilroy to task: “Who are you to lecture blacks in the United States, whom you conceive in the most egregiously undifferentiated way, about their international dissident responsibilities, while speaking of ‘We Britons’ … ?”

But as the dust has settled, younger people have made use of Between Camps. It “anticipated so many of the problems and questions that we are grappling with now,” says the US writer Asad Haider, who cited Gilroy’s work in Mistaken Identity, his 2018 book about the limits of narrow identity politics. Haider gives a first-hand account of a student politics campaign that broke down because groups devolved into bickering, racialised sub-groups. The key idea he takes from Gilroy is that “we have to go beyond the identity-based conception of politics to one of universal emancipation”. (“Bringing the word identity together with the word politics,” Gilroy once told me, “makes politics impossible, actually, for me, in any meaningful sense. Politics requires the abandonment of identity in a personal sense.”)

Gilroy doesn’t endorse a colour-blind politics that pretends the idea of race can be wished away. The post-racial world has to be fought for, against the odds. When Haider asked if Gilroy would provide a quote for his book, which he did, Gilroy sent him a favoured photograph of his, taken at the Manchester Pan-African Congress of 1945. The scene features placards with slogans like “Arabs and Jews united against British imperialism!” and “Labour with a white skin cannot emancipate itself while labour with a black skin is branded”.

In recent years, the appeal of an academic current known as Afropessimism has brought home just how untimely Gilroy’s ideas are. Its best-known proponent, Frank B Wilderson III, at the University of California, Irvine, contends that black people are viewed by all other people, including people of colour, consciously or not, as outside humanity. The result is that they are subject to a “gratuitous” violence that is unlike any other type of racism. To Wilderson, slavery is not a thing of the past – in fact, it has never really ended.

The rise of Afropessimism is a bleak sign for the likes of Gilroy, schooled on Stuart Hall’s argument that race is made politically meaningful through the struggle against capitalism, which is itself not eternal. Gilroy sees Afropessimism as part of an “ontological turn” – ontology is the study of being – in which race becomes an unassailable barrier between the self and the world, and anti-black violence an immutable fact. “What’s interesting to me is how resonant the Afropessimist outlook has proved to be,” Gilroy said. “I can’t help thinking that it’s got something to do with the fact that it absolves you of having to do anything at all. That really what you have to do is just be black. And there’s a sufficiency in that.”

In sharp contrast, Gilroy wants to reinvigorate an old ideal: humanism. In some scholarly circles, calling oneself a humanist can sound not just antiquated, but suspect. It was, after all, the name of the woolly ideology of equality propagated by Europeans at the height of empire, who spoke of the liberty of man while denying it to millions. But to Gilroy, there is hope in the promise of a radical humanism, illuminating a post-racial world. This, he believes, is the humanism of figures who regularly appear in his work such as Du Bois, Primo Levi, Toni Morrison and the French-Martinican revolutionary Frantz Fanon. If thinkers who had lived through the 20th century’s abominations could hold on to the idea of a humanism worthy of the name, then so can we.

Facebook Twitter Stuart Hall, writer, intellectual and co-supervisor of Gilroy’s PhD. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe/The Guardian

Gilroy’s prose can be difficult. His style is meditative, incantatory. He does not so much pursue a thesis in a linear fashion as solder ideas together into striking shapes. Writers, political figures and musicians are plucked from history and the present, placed in conversation with one another; a chapter might begin with two epigraphs, one from Walter Benjamin and the other from Michael Jackson. Sometimes the effect is frustrating, sometimes revelatory. A single poetic sentence might illuminate paragraphs of slow, swirling argument.

In 2019, after winning the Holberg prize, Gilroy travelled to Norway to give the laureate’s lecture, which he titled Refusing Race and Salvaging the Human. It is perhaps the clearest and most succinct statement of his worldview to date. “If you want to be serious about the struggle against racial orders,” he said, explaining his motivation behind the lecture, “you have to adapt your understanding of what it is to be a human being and why that is worth fighting over.”

The central scene is taken from the 1789 autobiography of Olaudah Equiano, the former slave and abolitionist. Equiano describes how he took control of a floundering ship during a storm in which the white crew had “become inert, apparently indifferent to their own fate”. With a few others, Equiano rescued the vessel, working so hard that the skin was flayed from his hands. Equiano’s actions scrambled the ship’s racial hierarchy. He was temporarily recognised as a kind of “chieftain” by the crew.

Gilroy’s point is that disasters can create the conditions in which we are forced to look beyond race towards our common humanity. What does he hate so much about race? It’s not just that it is a bogus concept, not just that it leaves behind it an endless trail of atrocities, but that, on a smaller scale, it tries to limit what a person can be, telling them that they are one thing or the other, rather than many things at once.

In the lecture, he offered this summary of his politics, which might be best imagined daubed on the walls of a future flooded city: “It is imperative to remain less interested in who or what we imagine ourselves to be than in what we can do for one another, both in today’s emergency conditions and in the grimmer circumstances that surely await us.”

Gilroy is rarely at a loss for words. As we walked on Hampstead Heath, he discussed why he left Yale in 2005. It was partly to do with the way his ideas were received, but there was something else. He came to a stop by a wooden fence. As he paused, the birdsong seemed to grow louder.

“I have a weird love of England. And London in particular,” he eventually said. “This is my home. God, it is. And I didn’t know it was until I went somewhere else.”

When I asked why this love was weird, he replied: “Because it’s ambivalent. And because it doesn’t love me back. It’s unrequited.”

He did, surprisingly, receive an invitation from Theresa May’s office in 2017 to be put forward for a CBE for “services to cultural and literary studies”. Gilroy wasn’t bothered so much about the imperial connotation of becoming a Commander of the British empire, as that was clearly “absurd”, but did find himself getting cross that the invitation came with a form about his ethnicity to fill in. “So the woman who is hounding my brothers and sisters to death over the Windrush scandal,” he told me in an email, “[wanted] to monitor my ethnicity while handing me a bauble. How fucked up was that?” He declined the invitation.

Facebook Twitter Finsbury Park in north London. Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian

In 2004’s After Empire, which he wrote while in the US, Gilroy puzzled over his homeland from afar. Why did it seem to be so stuck, unable to yield a different conception of what it might be? The obsession with the second world war – from the English anti-German football chant “Two World Wars, One World Cup” to the endless, commemorative flyovers of spitfires – troubled him. It seemed like a symptom of a society trapped in a warped image of the past: where the arrival of immigrants or refugees were spoken of as an act of invasion, where memories of the anti-Nazi war were stirred to justify interventions in the Middle East. He noticed that the “neurotic” fixation on the war went hand in hand with a carefully curated ignorance about empire and decolonisation – the brutal conflicts in Malaya, Ireland, Kenya and elsewhere. This stifling airlessness, this “postcolonial melancholia”, could also express itself through “outbursts of manic euphoria”, as Gilroy recently reminded his followers on Twitter in the hysterical run-up to England’s appearance in the Euro 2020 final.

But the book also offered a measure of hope. Gilroy saw stirrings of something positive in the hybrid styles and self-effacing humour of British pop culture – the Streets and Ali G are cited – but also in life as it was lived. Take the north London neighbourhood he has called home for almost 40 years, Finsbury Park. In the mind of England’s rightwing newspapers, it is a byword for social breakdown: a den of Islamism, haunted by the threat of inter-ethnic tension. The cleric Abu Hamza, currently serving life sentence in the US on terror charges, was once the imam of the local mosque. In 2017, it was attacked by a white supremacist.

In Gilroy’s view, to focus on this is to mistake the exception for the rule. He sees Finsbury Park as a “glorious expression” of actually existing multiculturalism, where racial differences are rendered banal by the flow of urban life. People in cities like London more or less get on, living side by side, with young people, in particular, developing cultures that mix styles, music and slang – the opposite of ethnic absolutism. Gilroy has elevated this observation into a theory, “conviviality”.

Affirming the creole pleasures of urban life isn’t enough, of course. The years after Gilroy wrote After Empire have seen the great recession, austerity, intensified gentrification, the fire at Grenfell Tower, and the pandemic, which has produced suffering for ethnic minorities at disproportionate rates. Convivial life is being tested. But it promises something more substantive, and hopeful, than mindless flag-waving.

He has always described himself as English, rather than British, he told me on Hampstead Heath. He loves England’s countryside, its folk music, its language. “I think I was worried with the idea of Britishness that it would only end up being the black and minority ethnic populations who took it seriously. Because it has no cultural content.” At that moment, a little greenfinch made itself heard. “They’re the ones I like the most to look at,” he said. “They’ve got very forked tails and they’re green. There’s something about the greenness of the greenfinch, and the way it complements the leaves … ”

“I hope I don’t sound patriotic,” he said, moments after talking about his claim on Englishness. “Patriotism is a betrayal of that attachment. Because it reduces it to some sort of formula.”

Gilroy is fond of the words of the Trinidadian historian CLR James, who wrote, in a 1969 essay, that “black studies” is the “history of western civilization. I can’t see it otherwise.” This might be the mission statement for what he imagines will be his final job: directing the newly formed Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the study of racism and racialisation at UCL. James’s point was that studying race shouldn’t be a parochial activity, but a way of understanding the world as it is for everyone. And as it might be. For Gilroy, this universalism is the whole point: the anti-racist struggle against police violence, he has emphasised in the past, should improve society for everyone, forcing the reform of “legal procedures that can impact on the lives of all citizens”.

Why every single statue should come down | Gary Younge Read more

At the end of The Black Atlantic, Gilroy wrote that the “colour line”, as WEB Du Bois termed the racial divisions etched across the globe, would soon no longer be the central axis of political conflict. It is still there, he told me, but the task is to see how it crisscrosses with other axes: health, wealth, gender, climate, technology. He wants his students to address race in a “planetary way”. At the UCL Centre, they will consider artificial intelligence, public health, borders: the architecture of 21st-century life.

But the past lurks in the shadows. Late last year, during his regular early-morning walks in Finsbury Park, Gilroy noticed something that echoed the racist graffiti he couldn’t escape as a child. Far-right vandals had been etching Celtic Crosses, a white supremacist symbol, into logs and tree stumps in the park during the night. “It’s the old circle with the cross through it,” he said. “A lot of neo-Nazi groups use the sign.” There’s an app through which you can report vandalism to the council, but he couldn’t be bothered to go through all that. “I’ve been rolling over the logs so it doesn’t show,” he said, “in the hope that no one will roll them back the other way.”

• This article was amended on 6 August 2021. The Holberg prize is not awarded by the Norwegian government, but is funded by it. This has been corrected.

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts here and sign up to the long read weekly email here.