Show caption King Kurt in February 1984. Photograph: Dpa Picture Alliance/Alamy Music Big quiffs, zombies and dead crows: the wild world of psychobilly The turbocharged twist on rockabilly enraptured 80s punks and rock’n’rollers – and alienated plenty more – with its food fights, ferocious club nights and phantasmagoria Michael Hann @michaelahann Fri 30 Jul 2021 09.00 BST Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share via Email

If you wanted to date the moment one of the biggest youth subcultures of 80s Britain arrived, you could pick 40 years ago this month, on 4 July 1981. That night, at the Marquee club in Soho, a few hundred kids gathered to watch a band who were almost singlehandedly kickstarting a new wave of alternative music. Waiting for them to come on, those fans launched into the song that served as their heroes’ unofficial theme, from David Lynch’s Eraserhead. “In heaven, everything is fine,” they sang. “You’ve got your good things, and I’ve got mine.” A few months later, that chorus opened, and gave its name to, the first LP by the Meteors. And as their frontman would later claim, “Only the Meteors are pure psychobilly.”

In time, psychobilly – a turbocharged twist on rockabilly, the country-enhanced variant on R&B that prefigured the classic rock’n’roll of the late 50s – would become codified. “My take on it would be a much more aggressive, loud approach to rockabilly that must include a double bass, modern lyrics – no cars, pinups or bubble gum – lots of graveyards, vampires, zombies, horror flick and death-influenced lyrics,” says Mark Harman of Restless, who came through the psychobilly scene in the early 80s. “Anything goes, really. Overdriven guitars and full rock drum kits, big quiffs, weird and wild clothing, makeup and props – blood and skeletons welcome. It should be fast and loud, exciting and fun.”

Lux Interior of the Cramps. Photograph: Peter Noble/Redferns

But in those early days, psychobilly was still unformed, part of a wider wave of bands in thrall to the whole span of primitive rock’n’roll. The Meteors mixed up their rockabilly rave-ups with covers of the Rolling Stones and the Electric Prunes. The Milkshakes, fronted by Billy Childish, were in thrall to the sound of Hamburg-era Beatles; the Sting-Rays played a version of garage rock laced with psychedelia; Restless were pure rockabilly; King Kurt played a Bo Diddley-esque R&B. The founding texts of this tidal wave of trash were records by the Cramps, and before them 60s garage bands such as the Sonics, or rockabilly wild men such as Hasil Adkins and the Phantom.

“I think it existed before the Meteors,” says that band’s original drummer, Mark Robertson. “I suppose the first record is Love Me by the Phantom [in 1958]. That’s psychobilly. I think the Cramps themselves said: ‘We didn’t invent anything, it was already there. You just had to look for it.’” If the word itself came from Johnny Cash describing a “Psycho-Billy Cadillac” in One Piece at a Time, the Cramps provided a convenient definition in the song Garbageman: “One half hillbilly and one half punk.”

The Meteors took that message to heart. Their singer/guitarist, P Paul Fenech, was a rock’n’roller, their bassist, Nigel Lewis, loved garage rock, and Robertson had been a punk. “We loved the Meteors at the very beginning, in their first incarnation,” says Alec Palao of the Sting-Rays, one of the groups who subsumed all those influences under the banner of “trash”. “All of us had grown up being equally into punk rock and discovering 50s and 60s stuff, and hearing the same kind of wildness in all of these things. So when we saw the Meteors, I was tremendously excited. It gave a legitimacy to this idea of not being a slave to retro authenticity.”

The Meteors backstage at Rock City, Nottingham, May 1981. Photograph: Dave Travis

If the history of punk tends to romanticise the musicians who saw it as an opportunity to explore, psychobilly and trash came from people whose interest in punk was driven by its simplicity. “Punk rock turned into that unpleasant David Bowie-type thing, the New Romantics, and that was very electronic and going away from what rock’n’roll was,” Childish says. As Palao puts it: “People got tired of the pseudo intellectualisation and overblown pomposity of the way rock was going. Punk rock neutralised that nicely, but then, sadly, a lot of those artists started going down the same pompous road as the people they were railing against.” That was the basis of trash: music for people who felt Magazine and Joy Division had got everything wrong.

The irony is that the rockabilly crowd disdained the psychobillies just as the psychobillies disdained sophistication. Robertson explains how in 1976, rock’n’roll-loving teddy boys, or teds, were fighting punks on Chelsea’s Kings Road. “The Sex Pistols would wind the teds up by wearing drapes. So the teds regarded that as a lack of respect. There would be pitched battles every Saturday between the two tribes. So when somebody came along who looked like rockabillies but played this thing that wasn’t authentic rockabilly, that was even worse.” The psychobillies, he says, were seen as “undercover punks out to destroy the rock’n’roll scene”.

After early Meteors gigs saw the band confronted by baseball-bat wielding rockabillies, they were forced to find their own audience, and develop their own gig circuit away from the traditional rock’n’roll clubs. “Our crowd was a mixture of rockabillies looking for something a bit more punky, and punks looking for something different,” says the band’s original manager, Nick Garrard. “We picked up a lot of the Adam and the Ants crew that lost interest in Adam when he became a pop star.”

In 1982, the trash bands got their own home, when the promoter John Curd set up the Klub Foot night at the Clarendon in Hammersmith, west London. “The Klub Foot was the Mecca for psychobilly and for neo-rockabilly,” Harman says. “It was always a sell-out – they’d come from all over the place. They were the wildest, greatest of times.”

“They were wonderful audiences to play for,” Palao says. “It was how I imagine the early days of punk rock, where everyone was jumping around having a great time. And then it gets formalised and people come in and it gets a little more sinister and violent, scary, [but] it wasn’t like that at the Klub Foot.”

Meteors fans developed their own dance, which spread across the scene, known as “wrecking”, which entailed little more than frantic flailing of the arms at whoever happened to be nearest. It looked violent, though participants viewed it as largely harmless fun. “It was really the Adam and the Ants crew coming in that created that wide-scale wrecking,” Robertson says. “It probably alienated some people. I suppose it’s the same as punk and pogoing. Pogoing was a vertical movement, this was more of a horizontal one. It was a rites of passage thing that certain young blokes need to go through. There was a certain element of proving yourself in that thing.”

Not everyone was impressed. “We despised all of that,” Childish says. “It was the total antithesis of what we were interested in. We wanted people to politely dance and enjoy themselves.” That said, he did not see it as unduly violent. “I saw it as strong male energy. They were quite joyful and exuberant, but anyone who was not into that was basically excluded from the front. If there was any fighting, which did sometimes happen, we’d just put down our instruments. When we got a lot of psychobillies coming along, because we played quite a lot of rock’n’roll, that’s when we introduced doing more ballads into the set to get rid of them. If they shouted out for a song, we’d shout back: ‘Keep your nose out of band affairs.’”

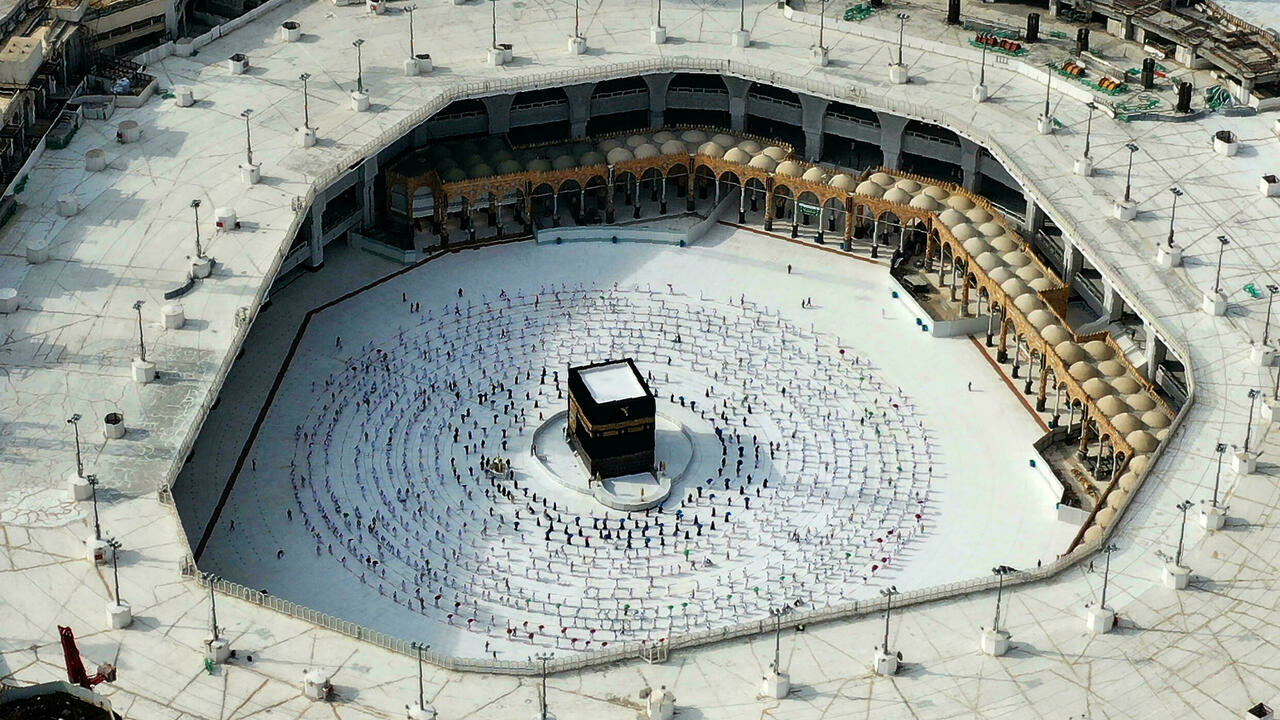

Psychobilly’s most notorious fans were attached to the most notorious band, King Kurt, the only psychobilly group to appear on Top of the Pops, when Destination Zululand reached No 36 in October 1983, and the band appeared with the drummer in excruciating blackface and caricature “tribal” dress.

Billy Childish (right, standing) and the Milkshakes in 1981. Photograph: Eugene Doyen

They initially attracted attention owing to the vertiginous nature of their hair, which was actually an accident, according to their singer, Smeg. “The original thing was that it was kind of like a veil, something to hide behind. It was more down than up. And the idea was that you couldn’t see my head when I was sitting on the tube. And it developed, as I gained confidence, into a more erect kind of affair. You see something you think is cool and then you take it to the nth degree, and that was the nth degree.”

And then the band started offering their fans haircuts, onstage. “We used to cut each other’s hair – nobody would do it in a barber’s – and then we thought: ‘Well, we can charge 20p a haircut.’ Because people would go to us: ‘Where d’you get your hair cut? Nobody’ll do it.’ So we started charging 20p and sometimes did it on stage if people were that way inclined. Some of them were better than others, it has to be said. And some people did come back and say: ‘I lost my job because I had this haircut.’”

Then there was the Wheel of Misfortune, in which a fan was plied with snakebite, then strapped to a wheel, vertically, and spun around (“Quite often people caught up with their own vomit at the bottom of the spin”); and food fights, which led to King Kurt being banned from big venues at the peak of their success because of the mess the group and fans created.

King Kurt in February 1984. Photograph: Dpa Picture Alliance/Alamy

As King Kurt’s notoriety spread, so their fans responded. “A lot of people were coming to see us and talking about how mad it was: people were throwing offal, seeing what was the weirdest thing they could bring to throw. One girl brought all the dead flies from those zappers you get in food outlets. She had this massive box of dead flies that she was throwing around. I remember drinking this pint and thinking it was full of sultanas, and she said: ‘I see you got some of the flies.’ Oh fuck. There was a geezer who lived on a farm. They used to shoot the jackdaws and crows, and he got arrested with two carrier bags full of dead crows. The police asked him what he was doing and he said: ‘I’m going to see a band.’ I don’t think they believed him.”

And the blackface? “Obviously there are people who see it as totally abhorrent. It wasn’t like we were hiding ourselves away and doing something malicious. Maybe it was ill-conceived, with hindsight.”

By the mid-80s, psychobilly was everywhere. The first Mark Fowler on EastEnders was a psychobilly (the actor who played him, David Scarboro, was a Klub Foot regular); the kids’ show Grange Hill had its resident psychobilly, Gripper Stebson. Every town had its contingent of flat-tops. But the closed nature of the scene meant it did not cross into the mainstream, and when the Clarendon was demolished in 1988, the UK scene lost its focal point and psychobilly went back underground.

Yet it never died, spreading around the world and kept alive by new bands and new fans, who also paid tribute to the original groups, many of whom still tour. Each year, pandemics allowing, the tribe assembles at Pineda de Mar in Spain for several days for the Psychobilly Meeting, where all varieties of trash are celebrated. But psychobilly is never celebrated outside the scene – no retrospective features in the heritage mags or reappraisals on Pitchfork. The Meteors used to write songs based on old horror films, and psychobilly’s place in alternative music is analogous to something from those movies: the evil mutant, chained up in the attic, where no one can see it.

Childish laughs at the description. “That wouldn’t actually displease some of the participants. I think they might be quite proud of that. And for me that wouldn’t actually be much of an insult. If you call it something that should be locked in the attic, that sounds like you’re writing the sleeve notes to one of their records. I’m sure they’d be pleased as punch with that.”

• The next Psychobilly Meeting is planned for 5-12 July 2022.