The dam near Luang Prabang – both a World Heritage site and an seismically active zone – is “an irresponsible gamble,” experts argue.

Building a huge dam just upstream from a legendary UNESCO World Heritage site in an earthquake prone region poses serious risk to the local population and the town of Luang Prabang, warns a leading Thai earthquake specialist.

Dr. Punya Churasiri, formerly the earthquake expert at Chulalungkorn University’s geology department, has considerable field research experience in northern Laos. As construction on the dam moved forward, he told The Diplomat, “We worry about what could happen and the possibility of damage to the World Heritage site.”

The main developer and builder of the dam is the Thai construction giant CH Karnchang corporation. The dam site sits precariously close to an active earthquake faultline only 8.6 kilometers away. A sharp reminder of the danger was provided on July 7, when a 4.7 strong earthquake was registered in Luang Prabang district.

Many local people in the World Heritage city fear that the 1410 MW Luang Prabang dam could trigger another disaster after the Xepian Xenamnoi dam accident in 2018. Damage to the dam caused a massive flood that swept away villagers and villages alike, leaving 14,440 people homeless and 71 confirmed dead.

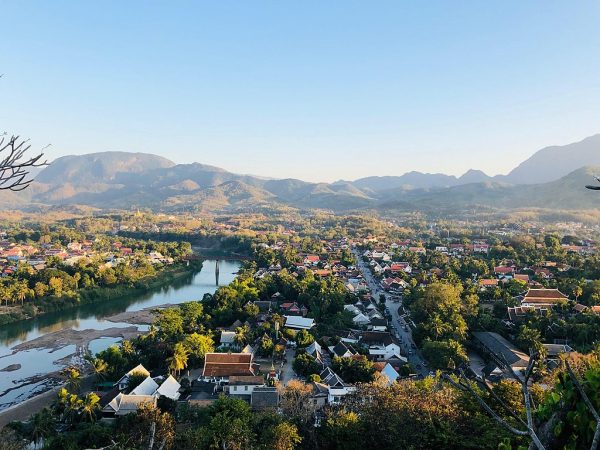

The dam site is 25 kilometers upriver from Luang Prabang, a cultural mecca and cornerstone of Lao history. The city harmoniously blends old architecture and culture with the surrounding nature, flanked by the confluence of the Mekong and Khan rivers, all part of the protective UNESCO World Heritage zone.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Among many issues UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee (WHC) will be considering at its annual session, which began on July 16 in China, will be the increasing impact of dams on World Heritage sites, most recently in the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania and Luang Prabang in Laos. The potential for damage to the sites has prompted global outcry. In the draft decision the WHC recommended the government of Laos “to halt all construction activities until a full heritage impact assessment is carried out.”

There is no question that northern Laos belongs to a highly active seismic region. In recent years, four earthquakes have occurred near the Xayaburi dam (130 km south of Luang Prabang) including a 6.9 magnitude earthquake in nearby Shan state of Myanmar whose effects spilled over into Laos on March 2011. In 2019, an earthquake of 6.4 magnitude hit northern Laos, with its epicenter not far from the Xayaburi dam.

Diplomat Brief Weekly Newsletter N Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific. Get the Newsletter

Although the Xayaburi Dam, the first dam to be completed on the lower Mekong, emerged unscathed, Dr. Punya Churasiri told The Diplomat, “They were quite lucky. That earthquake could have been much worse because there are several active faults near that dam.”

Doubts Over Dam Safety in Laos

The Luang Prabang dam is designed by the same Thai corporation, Ch. Karnchang, that built the Xayaburi Dam, which commenced operations in October 2019. Their international hydropower partner is Poyry Asia, based in Zurich, which has strategic involvement in both dams.

Punya was at one time a consultant with Ch. Karnchang and assigned to investigate earthquake faults in the vicinity of the dam-site.

However, he was upset with the company’s priorities as when they rushed ahead with construction plans. In particular, Punya was deeply concerned that “an active fault was located within a 30 km radius of the Xayaburi site.” He maintains that “the dam should never have been constructed, before the research into the danger had been completed.”

Similar fears have been raised by Nguyen Hong Phuong, a researcher at Vietnam’s Center for Earthquake and Tsunami Warning. In his report he stated that “[c]onstruction activity on the 32-metre-high dam, the first in a series of 11 planned in the area, could lead to more seismic activity in the region and threaten the Mekong’s downstream inhabitants in three countries.”

Mekong River Governance

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Over many years, people concerned about unregulated development along the Mekong River and issues such as dam safety have looked to the Mekong River Commission (MRC) to address problems and set standards of governance.

The MRC brings together the four riparian countries along the Mekong: Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam.

In 2011, the MRC secretariat observed that “[t]he recent earthquake near Xayaburi emphasizes the need for an independent dam safety review of the project according to international safety standards.” And yet the Lao government and the developers never established this independent review body.

Instead of an independent panel, according to the MRC Secretariat, “The Lao government engaged Poyry company as ‘owner’s engineer’ to review dam safety matters.”

Poyry (now renamed Afry) is the Zurich-based energy branch of a Finnish corporation. It was deeply involved in promoting the Xayaburi dam as a partisan consultant and was rewarded with a second contract to supervise the construction in partnership with Ch. Karnchang.

An owner’s engineer represents the owner of a project during design, development, and construction. In the case of the Xayaburi dam, Poyry was given the additional role of inspection in addition to their supervision of construction.

It may well be asked why the MRC experts did not query such a cozy conflict of interests, which hardly measures up to the need to comply with international standards of monitoring and due diligence. A spokesman for Poyry Energy in Bangkok denied there was any conflict of interest.

Dr. Martin Wieland, the managing director of Poyry Energy, insisted Poyry had taken earthquakes into account in its inspection. “The seismic hazard at the Xayaburi dam site has been studied thoroughly and the dam, the powerhouse, and the spillway will be designed against earthquakes, according to the latest seismic design guidelines prepared by the International Commission on Large Dams [ICOLD],” Wieland said.

Critics of the project point out that ICOLD is not an independent research body, but a forum for the dam engineering lobby largely funded by hydropower companies. Wieland of Poyry is also chairman of the committee on Seismic Aspects of Dam Design for ICOLD and in charge of seismic guidelines.

The Luang Prabang Dam

The MRC’s own technical review of Poyry’s Feasability Study for the Luang Prabang dam identified numerous risks to the ecosystem, and the need for stringent plans for dam safety. “The potential to impact a UNESCO World Heritage site further emphasizes the need to adopt the very highest standards of dam safety and emergency warning for this project,” according to a key passage in the MRC document.

But when it came to look at dam risks, the MRC review opted for a faster track modelling report carried out by the engineers from the Asian Institute of Technology, rather than actual field investigations by seismologists.

According to the MRC technical review section, “A Seismic Hazard Study assessment was elaborated at the Asian Institute of Technology based on seismic hazard analysis concepts and seismotectonic investigations to locate the Dien Bien Phu fault, which passes close to the Xayaburi site and which is capable of producing large earthquakes.”

Punya was not impressed. “Geology engineers have no expertise on earthquakes, that is just not good enough,” he responded.” The AIT specialists were primarily concerned with ensuring the capacity of dam walls for earthquake resistance, he continued, “but seismology is also concerned with a wider range of threats. A cascade of dams can trigger reservoir-induced seismicity” and that also needs to be investigated.

Japanese Professor Hiroshi Hori, who has extensively looked into the interaction between dams and seismic risk, has also warned of the connection. He concluded in his book “The Mekong: Environment and Development,” “The chances for earthquakes to occur in earthquake-prone zones increase in accordance with the effects of either water impoundment or reservoir operation. Earthquakes still take place even when dams are built, in regions where no previous quakes have been recorded.”

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Earthquakes are hard to predict, but we do know the triggers for earthquakes can be man-made. Building dams in a region of frequent earthquakes is tempting fate, especially in a country that has notoriously lax safety standards.

Can UNESCO’s Heritage Impact Assessment Affect the Outcome?

With so many disturbing safety issues and a flood of environmental objections, why choose such a sensitive, high-risk site brimming with potential as the location for the next dam disaster?

“All this process by the MRC is at best attempting to mitigate entirely unnecessary damage due to the flawed choice of the dam site,” said Professor Jian-hua Meng, a water security and hydropower advisor to the WWF.

“Many less ecologically- and culturally- sensitive sites could have been developed faster, and with significantly less risk to food security of the downstream countries,” Meng added. “It is an irresponsible gamble.”

UNESCO’s WHC can ensure that its Heritage Impact Assessment is effective in considering the unacceptable degree of dam risk and environmental damage, going beyond the narrow scope of MRC consultations.

The World Heritage Committee has been vocal in raising concerns about the increasing threat that dams pose, and passed a resolution in 2016 calling for the prohibition on dams within the boundaries of World Heritage sites, as well as for any dams indirectly impacting these sites to be “rigorously assessed.”

The Heritage Impact Assessment should determine whether UNESCO will call for the cancellation of the dam or eventually place Luang Prabang on the World Heritage Endangered List.

Punya was very clear about what would happen in his own country in similar circumstances. He concluded: “No dam should go ahead without more detailed study of faultlines, to demonstrate it is safe. But if this happened to be a dam proposal next to a cultural heritage site in Thailand, no dam would be allowed to go ahead.”