It came as no surprise to see Farida Khelfa sitting in the front row at last week’s fashion shows in Paris, with her signature cropped haircut and wide smile. Two of the biggest shows were essentially tributes to Azzedine Alaia and Jean Paul Gaultier, designers who took inspiration from and helped elevate Khelfa to supermodel status in the 1980s.

As a teenager, Khelfa ran away from her strict Algerian family in Lyon, and was discovered while working at a Parisian nightclub.

She still occasionally models, most recently for Fendi’s spring couture collection, but today Khelfa, 61, is more focused on filmmaking. In 2012, she released a documentary about the Arab Spring, filmed in Tunisia shortly after the fall of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. She has also made films about her friends Christian Louboutin and Gaultier.

Earlier this month, she released De L’autre Cote du Voile (On the Other Side of the Veil) on her YouTube channel. Through a series of interviews – starting with designers, then expanding to artists, a chef, a nonprofit worker and more – Khelfa said she wanted to offer a new perspective on women living and working in the Middle East.

This conversation was condensed and edited for clarity.

Q: Did any of the women you interviewed surprise you or challenge your own notions of Muslim women?

A: The one who surprised me is the woman who was totally veiled, Ghadah Al Rabee. She’s an artist, and her husband is working with her – for her. She’s the lead in the couple, you can tell, and she’s totally covered. Her work is so alive, and she’s very funny.

For me it was like: how can you be an artist and be totally covered? But then I understood it was a statement. I remember when I was in New York, during the Eighties, there were some artists who arrived totally naked at their opening. In a way, that was a statement.

Farida Khelfa at the Dior show during Paris Fashion Week (Getty)

Q: Another artist, Manal Al Dowayan, says that Saudi women are generally depicted in one of two ways: the activist who ends up in jail or the veiled and oppressed victim. She says women in the middle, working towards change within the system, are ignored. Do you agree with that?

A: I think so. The oppressed women, we have to think about them. But I think it’s more constructive and more interesting to talk about the women who look like us. We can refer to them. They want to work, they want to have money, they want to have a family or not have a family. We have the same dreams. We’re the same.

Q: When you started modelling, did you find that people had a stereotypical image of you as a Muslim woman?

A: No, because society wasn’t that obsessed with the stereotype. I didn’t have any problems.

Fashion is not racist. Fashion is open. If you bring something to fashion, the designer likes you, the photographer likes you, and you work.

But because I was raised in the Muslim world, it was very difficult for me to be doing things like lingerie. I cannot do lingerie. Even being photographed was complicated for me.

Q: Did your parents support your career?

A: No, my parents never supported it. But I never asked for that.

Q: What’s the biggest difference you see in modelling today, compared to your early years?

A: First of all, there are so many models – so, so, so many. The industry has changed completely. It’s much more business-minded. When I did the shows, when we were walking, people were screaming your name like you were in a concert. It was totally crazy.

Now you can tell they want to sell bags. It’s a different world. It doesn’t create the same kind of energy, when you see models walk straight and look at the camera to have the best profile. We really didn’t look at the camera. We were smoking when we walked! You cannot do that anymore.

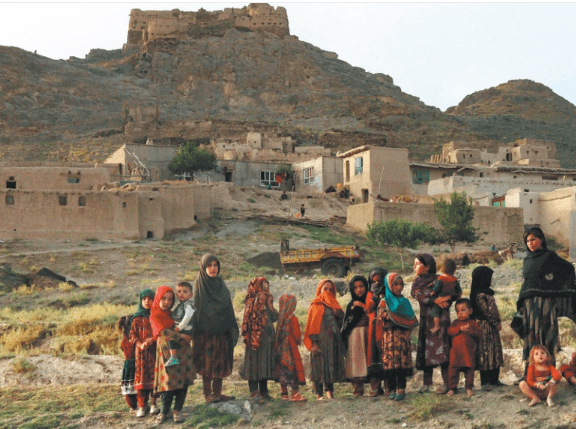

Modelling Fendi’s spring couture collection (AFP via Getty)

Q: Is it more difficult for models to change careers?

A: So many models feel really bad towards the end of their careers – in their 30s. When the phone doesn’t ring anymore, suddenly you understand that you’re out of the game.

You have to think in advance. You have to be prepared. But we’re never prepared for failure. And failure is very important. Success is very rare, and it doesn’t last. Most of the time you fail.

Q: You’ve said that your next film will be about your own life.

A: It’s not a documentary. It’s going to be fiction and nonfiction, mixed.

It’s not easy to share your story. That’s why it’s a mix of fiction and nonfiction – because I cannot write a book. I cannot, because if you write a book, you have to say everything, and I cannot.

But in a film, and just with an image, you can say so many things. You don’t need words, just an image. That’s why I love cinema.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times