IN THE HOME state of Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, a person too clever by half is said to have won the house, but lost Gujarat. Through March and April, political pundits voiced the Gujarati proverb as a warning. So fiercely were Mr Modi and his Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) fighting to win elections in another state, West Bengal, that they risked losing a bigger prize. Focused obsessively on the campaign through eight rounds of voting that ended on April 29th, they failed to pay attention as India’s second wave of covid-19 grew from a worrying swell into a tidal wave—the biggest cataclysm to have struck the country in living memory. What good would it be if Mr Modi unseated Mamata Banerjee, the obstreperous opposition leader in West Bengal, if his apparent lack of interest in the mounting body-count from the pandemic shook the whole country’s confidence in his leadership.

The country’s confidence is indeed being shaken. Every day sees grisly new records, either in the number of new infections of covid-19, or in the number of deaths from it. Debilitating shortages of oxygen and hospital beds appear to be spreading as the second wave washes across new regions. Frantic relatives of ailing patients have to hunt and beg for life-saving treatment—often unsuccessfully. On May 1st alone official records show 3,689 deaths, and that is almost certainly a woeful undercount.

To make matters worse, when West Bengal’s votes were tallied on May 2nd, along with those in three other states, Mr Modi did not even capture the benefit for which he has jeopardised his national standing. As widely expected, the BJP did keep a hold on one state, Assam (population 36m). In the two far-southern states of Kerala (population 35m), and Tamil Nadu (population 82m) it failed to secure a single seat. This rebuff to a party that is strongest in India’s Hindi-speaking north was not unusual, but still a setback. In Kerala voters handed a resounding victory to an alliance of leftists that is viscerally opposed to Mr Modi’s Hindu nationalism, and in Tamil Nadu they trounced the BJP’s local ally, opting instead for an ally of Congress, the BJP’s historical rival in national politics.

Yet it was in West Bengal (population 91m) that Mr Modi suffered the greatest humiliation. The prime minister himself had hosted some 20 giant rallies across the state, and devoted immense amounts of money and manpower to the fight. His closest henchman and electoral supremo, Amit Shah, the home minister, brashly predicted that the BJP would grab more than 200 of the state assembly’s 294 seats. The outcome was precisely the opposite. Mr Modi’s party captured just 77 seats. Its chief opponent, Ms Banerjee’s All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) sailed home with a cool 213. Shekhar Gupta, a journalist, describes this as the most significant electoral defeat of Mr Modi’s seven years in government.

Why should the loss of—or rather, failure to capture—just one of India’s 28 states be so important? The answer is that not only the BJP, but also its sister organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a tentacular fraternity that underpins the Hindu-nationalist movement, portrayed the contest in West Bengal as a show of strength. They wanted a victory to prove that Hindu nationalism could thrive anywhere in India, even in a region where Hindi is not the main language, with a distinct culture and a strong secular tradition.

The TMC has done little to revive West Bengal’s lumbering economy. The state is also marked by stark social divisions, including those between the Hindu majority and a Muslim minority of nearly 30%. Mr Modi has successfully exploited conditions like these again and again, with one hand promising money, development and progress, and with the other a club to put “anti-nationals” such as Muslims in their place.

The party’s campaign in West Bengal was ugly even by the often unseemly standards of Indian politics. Mr Shah repeatedly insinuated that local Muslims are in fact dangerous Bangladeshi “infiltrators” out to steal “Indian” jobs. He excoriated Ms Banerjee for “appeasing” them with handouts. Other figures in the party publicly gloated when Muslim voters were shot dead by police during a fracas at a polling booth. In an astonishing lapse of taste during a pandemic, the BJP loudly advertised that if elected, it would give everyone in the state free vaccines for covid-19.

None of this seems to have worked. West Bengal’s voters did not turn against the BJP because of Mr Modi’s disregard for social distancing in the midst of a pandemic, or to punish him for his government’s failure to handle the disease’s second wave. Half of the eight phases of voting in the state took place before the number of infections and deaths began to soar. Many also did not vote for the TMC out of love for the party, which is widely seen as thuggish and corrupt. They voted simply to keep the BJP out of power. Muslims, importantly, voted strategically, rejecting “Islamic” parties and abandoning secular alternatives such as Congress and communists in order to concentrate all their strength in the party most likely to ward off Mr Modi.

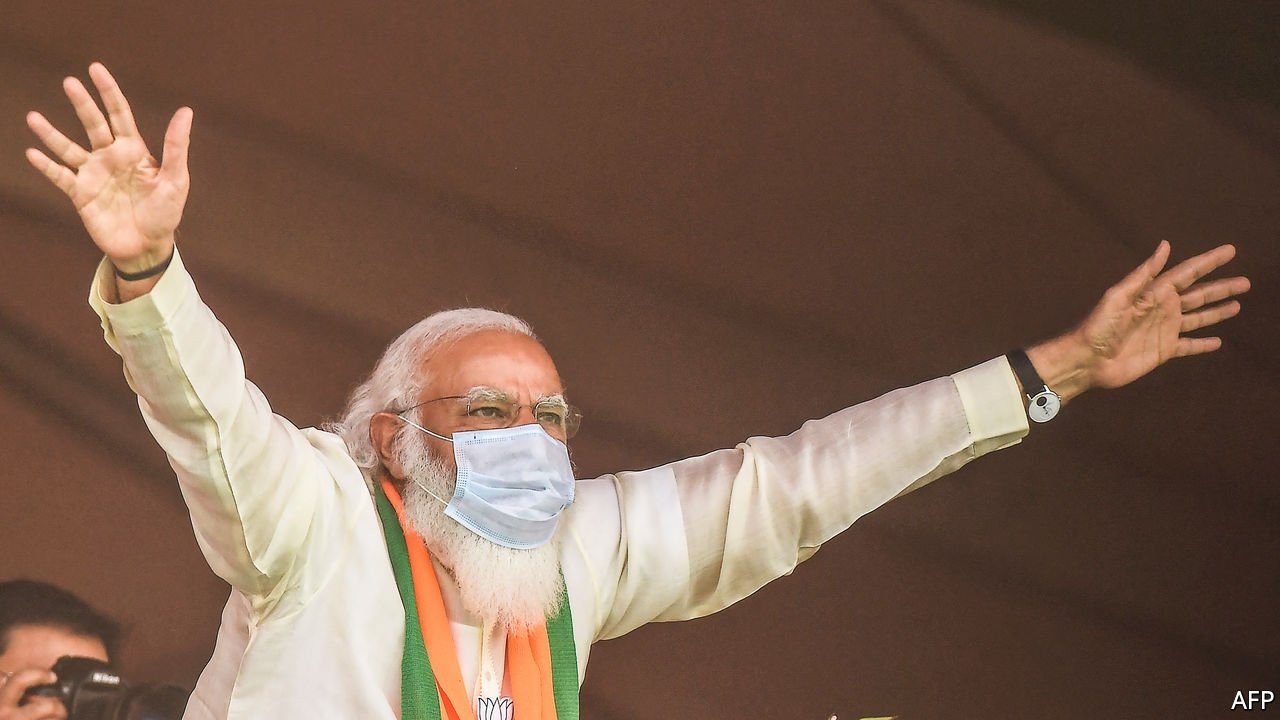

With the official death toll from covid-19 nearing 220,000 by May 2nd, and media airing mortifying imagery of blazing pyres and dying patients gasping for oxygen, Mr Modi now faces a ferocious backlash from beyond West Bengal. Carefully cultivated over three decades in politics, his reputation for dynamism, patriotism and compassion for the little man has been shredded. The trouble is not just his government’s failure to anticipate, plan for and now cope with India’s devastating second wave. What has shocked millions of Indians, including much of his own base, is Mr Modi’s deafness to widespread suffering. At one rally in West Bengal in mid-April, he actually joked delightedly at the size of the largely unmasked crowd. As the misery has mounted, he seems to have grown more distant, avoiding the limelight and commenting in increasingly stilted soundbites.

Yet neither the BJP’s electoral setbacks nor the political damage from covid-19 represent immediate threats to Mr Modi. Morning Consult, a political monitor, reckons that his popularity rating has fallen to its lowest level since the beginning of his current term, and by seven points in the past month alone. Yet at 67% it remains enviably buoyant. His party, too, is more resilient than a few poor state results might suggest. “The BJP is very good at quietly reviewing its mistakes and learning from them,” says Kapil Komireddi, author of a critical book on the Modi era. “Don’t write them off. They will work harder.”

With three strengthened regional leaders now grandstanding from the post-poll states, and with Mr Modi’s standing shaken by the covid-19 debacle, other regional opposition leaders may be emboldened. India’s mainstream press, largely cowed by the ruling party’s money and clout, as well as by Mr Shah’s ruthlessness, has also grown less craven as evidence of the government’s callousness and incompetence has grown impossible to ignore.

But pulling all of Mr Modi’s critics into a political force strong enough to challenge him at the national level is another matter. India’s once-dominant Congress party, from which many of the regional players, including Ms Banerjee, emerged, lacks the drive and energy to rally and galvanise the opposition. Its leader, Rahul Gandhi, has ironically been prophetic about covid-19, repeatedly and accurately chiding Mr Modi for failing to take the threat seriously enough. But Mr Gandhi is not backed by an effective machine, and as the scion of a venerable political dynasty he remains vulnerable to Mr Modi’s anti-elitist jibes. “He harms the message by being the messenger,” says Mr Komireddi.